- 262 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

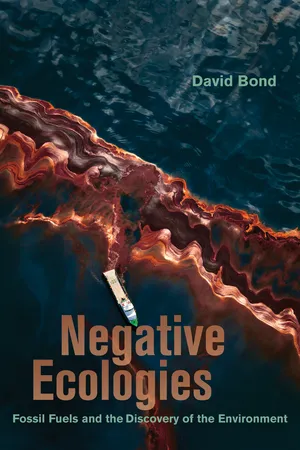

About this book

So much of what we know of clean water, clean air, and now a stable climate rests on how fossil fuels first disrupted them. Negative Ecologies is a bold reappraisal of the outsized role fossil fuels have played in making the environment visible, factual, and politically operable in North America. Following stories of hydrocarbon harm that lay the groundwork for environmental science and policy, this book brings into clear focus the dialectic between the negative ecologies of fossil fuels and the ongoing discovery of the environment. Exploring iconic sites of the oil economy, ranging from leaky Caribbean refineries to deepwater oil spills, from the petrochemical fallout of plastics manufacturing to the extractive frontiers of Canada, Negative Ecologies documents the upheavals, injuries, and disasters that have long accompanied fossil fuels and the manner in which our solutions have often been less about confronting the cause than managing the effects. This history of our present promises to re-situate scholarly understandings of fossil fuels and renovate environmental critique today. David Bond challenges us to consider what forms of critical engagement may now be needed to both confront the deleterious properties of fossil fuels and envision ways of living beyond them.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Negative Ecologies by David Bond in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biowissenschaften & Umweltrecht. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Environment

A Disastrous History of the Hydrocarbon Present

Is the environment worth the effort? The environment often seems far too easy, far too obligatory, and far too footloose a concept to warrant serious attention. It somehow evokes both bookish abstraction and populist rousing, it cobbles together science and advocacy only to blunt their conjoined insights, and it continues to elude fixed definition even while basking in stately recognition. The banalities of this mess can give the impression that the environment has no real history, has no critical content, and heralds no true rupture of thought and practice. The environment, in the eyes of some, is mere advertising. If there is a story to the environment, others suggest, it’s largely one of misplaced materialism, middle-class aesthetics, and first world problems. Such has been the sentiment, such has been the dismissal.

In the rush to move past the environment, few have attended to the history of the concept. This is curious, as the constitution of the environment remains a surprisingly recent achievement. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the environment shifted from an erudite shorthand for the influence of context to the premier diagnostic of a troubling new world of induced precarity (whether called Umwelt, l’environnement, medio ambiente, huanjing, mazingira, or lingkungan).1 While the resulting recognition of the environment largely consisted of bringing existing problems together under one umbrella—factory pollution, urban sewage, radioactive fallout, automobile emissions, garbage disposal, and even climate change—the resulting synthesis was powerful.2 It was almost as if a light had been switched on to reveal a whole new world of toxic trespass. Such illumination—what historian Joachim Radkau (2014) has called “a New Enlightenment”—posed an unsettling provocation: perhaps progress was not achieved autonomy from the natural world but waves of profit and power undermining the very basis of life. As shorthand for the resulting crisis of life, the environment became an insurgent field devoted to understanding damaged life and taking responsibility for it. Despite scholarly attempts to bury the term within more established histories, the environment signaled something profoundly new for outraged citizens, concerned scientists, and savvy politicians.3

The novelty of the environment did not pass without notice. Celebrating its recent arrival, Time magazine named the “environment” the issue of the year in 1971. When fifty paperbacks on the discovery of the environment were published in 1970 alone, a New York Times reviewer described being “inundated by books on the environment” (Shepard 1970: 3). While drawing very different conclusions, these books almost uniformly noted how the environment drew the ailing “life support systems” of Earth into unsettling focus. Privileging the pragmatics of human survival over inherited precepts, the environment introduced an impending future as the new guidebook for moral conduct and political action in the present. A French minister called l’environnement an “imperialist” term for how quickly it infiltrated the country, demanding new oversight within the most ordinary of places and practices (Poujade 1975: 27). The family automobile, dishwashing detergents, and plastic bags found themselves suddenly shot through with planetary significance. Astounded at the range of the concept, ecologist Paul Shepard (1970: 3) insisted the environment “is genuinely new in its planetary perspective and connection to war, poverty, and social injustice.” The novelist Isaac Asimov (1970: A9) summarized the sentiment: “Environment has become a magical word,” he wrote in 1970, drawing together the ordinary and the planetary, our present plight and our future ends.

During the 1970s, the environment rather suddenly became “a household word and a potent political force,” as one White House report reflected (CEQ 1979: 5). Prompted by a somber announcement from the UN secretary general that “it is apparent that if current trends continue, the future of life on Earth could be endangered,” the United Nations (UN) organized a conference on the human environment in 1972 (UN 1969: 10; Ward and Dubos 1972). Within two decades nearly every government had commissioned a new agency or ministry to protect the environment. In the United States, environmental studies was inaugurated on college campuses across the nation, and major newspapers added an “environment beat.” Whole subfields in environmental law and environmental science sprang up almost overnight. The environment—a term “once so infrequent and now becoming so universal,” as the director of the Nature Conservatory commented in 1973 (Nicholson 1970: 5)—soon came to monopolize popular and scientific understandings of damaged life and the state’s obligation to it. The environment emerged as “a crisis concept,” write historians Paul Warde, Libby Robin, and Sverker Sörlin (2018: 23), born in peacetime prosperity pricked by a dawning sense of doom. Visualizing the synthetic webs underlying and undermining the modern project, the environment advanced a theory of entangled life beyond the nature/culture dualism. Vividly documenting the basis of life slipping just beyond the fixtures of modernist control, the environment offered a precocious theory of the Anthropocene. To the great misfortune of contemporary scholars scrambling for the title of first author, this early theory of manufactured disarray was most substantially advanced by the state.

While much as been made about how this crisis of life helped lay the affective groundwork for the rise of environmentalism (Gottlieb 1993; Worster 1994; Sellers 2012), much less attention has focused on the underlying materiality of this crisis.4 As the resulting social movement holds the attention of scholars and citizens alike, the physical ruptures these campaigns responded to has drifted out of focus. Many of the specific problems that provoked what became known as “the environmental crisis” had their basis in what Rachel Carson (1962: 11) once called “the wonder world” of hydrocarbon innovation in post–World War II America. As two leading public health officials noted in 1955: “The recent advent of the atomic age, the era of synthetics, and the petroleum economy, when combined with epidemiological observations, indicate that a general population hazard is of more than theoretical significance” (Kotin and Hueper 1955: 331). By the 1960s, ecologists were learning to see just how thoroughly two icons of modern power—fossil fuels and the atomic bomb—had infiltrated the very fabric of life. Christened “our synthetic environment” by Murray Bookchin (1962), this scientific recognition of porosity and precarity punctured the modernist swagger of modular control. While the specific instances of injury were incredibly wide-ranging, the cause was surprisingly uniform: hydrocarbon emissions, petrochemical runoff, and radioactive fallout. In other words, the material basis of American prosperity and power in the twentieth century.

Resituating the environment around American ascendance places the emergent crisis of life and resulting structure of feeling on a more imperial foundation of disruption.5 Rather than starting with the instigated social movement—environmentalism—and grasping the world from within its mobilized outlook or starting within the resulting domain of objectivity—environmental science and policy—and grasping the world from their already normalized overlay of toxicity and life, this book begins with the surplus of synthetic force that sparked the founding crisis. Emphasizing the messy materiality of “the environmental crisis” of the late 1960s can situate the protests and institutions that gave rise to the environment in the 1970s without too tightly bounding scholarly inquiry to their “post-material” suburban and state forms (Inglehart 1981). However provisionally, this also brings American empire into focus as an early provocateur of what Jane Bennett (2009) calls “vital matter” and others have taken up as the earth-shattering insight of nonhuman agency.

Many contemporary scholars newly smitten with the agency of the material world are swept up in a kind of utopian outlook, where a profound pessimism of the political conspires with a newfound optimism of the physical. Such work collapses all frustration with the shortcomings of existing politics into the fogged vision of human exceptionalism, suggesting that if we can only recognize the vibrant liveliness of the worlds beyond the human, a truly emancipatory politics will bloom organically from the rubble of the modern episteme. The most radical task, then, is to simply understand the world differently, to bracket a few centuries of history as comprehensive failure and look forward to the worlds to come. Perhaps this may hold promise with the ontological force of mushrooms, rivers, forests, and mountains, to name a few of the more consequential reworkings of materiality in anthropology today. But the sweeping optimism of this current of thought often ignores the more destructive agencies that enliven our present (or worse, may find misplaced optimism in their destructive capacities). What of the ontological force of toxic destruction and pandemic disease? Is the celebration of their agency also emancipatory? Or, paraphrasing Taussig (2018: 18), what if it is the viral terror of the contemporary that has endowed the natural world with a vitality that scholars only grasp in proliferating agencies divorced from history? The explosive force and “slow violence” of fossil fuels and nuclear weapons bring a very political history to these questions of agency, one saturated with the petrochemical and radioactive foundation of American empire in the twentieth century (Nixon 2011; Immerwahr 2019). Yet today, this history of synthetic force in the imperial rise and reach of the United States, writes Adam Hanieh (2021: 28), “sits elephant-like within the ecological crisis of the present.”

FIGURE 2. 2014 Peoples Climate March. Photo by author.

Such critical connections were closer to the surface during the rise of the environmental crisis. For writers like Rachel Carson and Barry Commoner, America’s rising reliance on fossil fuels and nuclear weapons introduced a profoundly destructive agency into the world. This haunting corrosion of life came into analytical focus precisely for the open-ended harm it caused, and by foregrounding the entangled webs of harm unleashed by the fallout of petrochemicals and radioactivity, their public scholarship sketched out a still unfinished critique of American empire. In sharp contrast to the new materialism of contemporary scholarship, their writing disallowed any deferment of history in the reckoning with the futures already at work within us and refused any celebration of an emancipatory politics from the mere recognition of material agency. Moreover, the legacy of their work also demonstrates how a radical opening to material agency and entangled life did not, in itself, conjure a revolutionary politics so much as authorize new scientific and regulatory fields of technocratic control within the nation-state.

THE NEGATIVE ECOLOGIES OF POWER

In so many ways, the sudden and widespread realization of the environment was underwritten by the excessive synthetic materiality of American power. As many have argued, the properties of fossil fuels and atomic energy introduced a new material basis for coercive accumulation and authority and a new infrastructure for imperial projections of structural retribution and cultural aspiration that helped align the world with designs for a new American order.6 Yet the unique properties of fossil fuels and atomic energy reached far beyond the coffers of corporations and the clenched fist of the state. Something of their force exceeded capture within positive iterations of wealth and influence. Something of their force made its way beyond capitalism and state power and into the fabric of life itself. And as they defied existing jurisdictions and disciplines and came to suggest worlds of consequence in gross surplus of their cause, these problems came to demand a new accounting.

Centering negative excess has a pedigreed intellectual genealogy. In 1947, Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno posed new questions about the excessive underside of modern power. Whether in trench warfare, administrated genocide, or suburban ease, an unprecedented union of “machines, chemicals, and organizational powers” ([1947] 2002: 184) promised to launch human might beyond the gravity of history and nature. For Horkheimer and Adorno, the concerted effort inaugurated a new “epoch of the earth’s history” (184) founded on the divorce of jagged historical realities from the scientific pursuit of unfettered power, the privileging of a life of ease over any obligation to care, and the repression of an imploding present under the banner of a more perfect future. Reason metastasized from a ladder of critical enlightenment into the author of oblivious annihilation. Almost as if self-driven, the resulting “motorized history” (xv) rushed ahead of any political accountability, let alone revolutionary resistance. By way of the automobile, DDT, and atomic weapons, Horkheimer and Adorno sketched out “the calamity which reason alone cannot avert” (187). Instead, they wrote of the postwar moment: “The hope for better conditions, insofar as it is not an illusion, is founded less on the assurance that those conditions are guaranteed, sustainable, and final than on a lack of respect for what is so firmly ensconced amid general suffering” (186). And it is from the dark alleyways and deformed lives of the catastrophic ascendance of instrumental reason that such promising disrespect resides. (As Adorno wrote at the time, “automobile junk yards and drowned cats, all of these apocryphal realms on the edges of civilization move suddenly into the center,” quoted in Buck-Morss 1977: 189). Such work resituates the negative not as a fundamental lack but as a provisional grasp of reality in defiance of tyrannical rationality.

Twenty years on, and Theodor Adorno only deepened his conviction of negativity as the most philosophically astute, politically uncompromised, and empirically potent realm of the contemporary. “After the catastrophes that have happened, and in view of the catastrophes to come, it would be cynical to say that a plan for a better world is manifested in history and unites it,” wrote Adorno in Negative Dialectics ([1966] 2007: 320). Recoiling at the human fodder readily fed into the crackpot utopias of both liberalism and state socialism did not mean admitting critical theory could not counter the crisis at scale. It meant rooting critique in the historical necessity of change inoculated from the corporate dogma of technical progress. If no overarching spirit of redemption unified recent historical experience, there was still the possibility of a more encompassing home for critical theory. “No universal history leads from savagery to humanism, but there is one leading from the slingshot to the megaton bomb”(Adorno 2007: 320; see also Vázquez-Arroyo 2008; Chakrabarty 2009). Whether in lingering memories of concentration camps or rising fears of impending nuclear war (or, we might add, all of those places where the Cold War was anything but), a jilted sensibility of unbound destruction had become ordinary. “Absolute negativity is in plain sight” (Adorno 2007: 362). Such negativity may be ubiquitous, but such realities were also conceptually invisible. Negative realities were obscured by the omnipotent optimism of instrumental reason projecting redemptive futures. Yet for Adorno, the negative does not exist within the shadow of the positive. The rippling losses are not secondary, peripheral, subordinate, or ancillary to speculative growth. The losses were fast becoming the more definitive reality. How might centering negativity help prick the positivist plague of instrumental reason and stage a more potent politics of transformation? Not only is nonsensical destruction the direct consequence of the teleological pursuit of capital, but the injuries sustained grossly exceed the amassed gain. Unloosed ruin is the very landscape upon which categorical progress gains viral force and, on pain of waking up, cannot acknowledge. With revolutionary demurral, Adorno looked to negativity as proliferating instances tripping up the imperial conceit of progress. Against the omnivorous ideological appetite and relentless synthetic acceleration of capitalized history, a modern whirlwind that seemed capable of bending any inkling of conceptual optimism into widening projects of dispossession and devastation, the negative alone refused easy recruitment. Standing just outside the infectious mantra of mutually assured redemption through unrestricted force, the negative rebuffed philosophical appeasement and political reconciliation. It glimpsed an entirely different reality. Negative dialectics, for Adorno, roots inquiry and intervention within “the extremity that eludes the concept,” for anything else would merely provide “musical accompaniment” to annihilation (365).7 Far from a political identification with the forces of destruction or celebration of the baptism of coming catastrophe, laying the emphasis on negativity gave credence to the present impossibility of current arrangements. To negate the negative you first have to take it seriously. Prioritizing the bruised and broken came to seed grand delusions of fueled progress with “epitomes of discontinuity” (320) that tripped up the otherwise relentless acceleration of history. Inhabiting experiences of negativity offered critical theory a way to grasp the present from within its historical momentum but not determined by it: experiences of negativity repulsed incorporation into instrumental reason, anchored the apprehension of reality in common destruction without validating utopian redemption, and opened a doorway to seize upon radical possibility from within a motorized history already derailed. In this insistence on the priority of the negative, Adorno was not alone.

Eugene Odum’s classic textbook, Fundamentals of Ecology (1953), oriented the emerging science of ecology toward the relations that energized life. Documenting a cycling between animate and inanimate, ecology found life suspended within intricately balanced circulations of matter.8 A decade later, a number of scholars and writers turned Odum’s insights away from the isolated mountain ponds that populated his textbook and toward the manufactured present. Rachel Carson, Barry Commoner, and others drew on ecology to query vital biochemical cycles being thrown into disarray by the noxious excess of factories, power plants, automobiles, fertilizers, and nuclear testing. Observing the ease with which petrochemical pollution and radioactive waste joined the chemistry animating life, often to disastrous effect, they centered their inquiry on “the webs of life—or death—that scientists know as ecology,” as Rachel Carson (1962: 189) put it. This was an ecology that refused an outside to the industrial and militarized landscapes of the contemporary world. The subject of this renegade ecology was resolutely present tense: the split personality of American postwar society, possessed of both synthetic prosperity and biological precarity for which there was little precedent. Turning toward the his...

Table of contents

- Subvention

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction: The Promise and Predicament of Crude Oil

- 1. Environment: A Disastrous History of the Hydrocarbon Present

- 2. Governing Disaster

- 3. Ethical Oil

- 4. Occupying the Implication

- 5. Petrochemical Fallout

- 6. The Ecological Mangrove

- Conclusion: Negative Ecologies and the Discovery of the Environment

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- References

- Index