![]()

PART ONE

Diagnosis

and Treatment

![]()

1

Understanding Cancer

Malin Dollinger, M.D., Andrew H. Ko, M.D.,

Ernest H. Rosenbaum, M.D., and David A. Foster, Ph.D.

Cancer is a general term for the abnormal growth of cells. Cells are the building blocks of our bodies. Every normal cell contains twenty-three pairs of chromosomes. Winding through each pair is the double helix of the DNA molecule, the genetic blueprint for life. DNA is the controller and transmitter of the genetic characteristics in the chromosomes we inherit from our parents and pass on to our children.

Our chromosomes contain millions of different genes—pieces of DNA containing information on how the body should grow, function, and behave. Genes determine the color of our eyes, tell injured tissues how to repair themselves, tell our stomachs how to make gastric juice, and direct the female breasts to make milk after a baby is born. Most of the time, these genes function properly and send the right messages. We remain in good health, with everything working as it should.

But there are an incredible number of genes and an unimaginable number of messages. And since the chromosomes reproduce themselves every time a cell divides, there are lots of opportunities for something to go wrong. Although the vast majority of “mistakes” that occur during chromosome reproduction or from damage by external factors are repaired by the body, sometimes something does go wrong in the process of cell division—a mutation that alters one or more of the genes.

Cancer results from genetic change or damage to a chromosome within a cell. The altered gene sends the wrong message or a different message from the one it should give. A cell begins to grow rapidly. It multiplies again and again until it forms a lump that’s called a malignant tumor, or cancer.

Uncontrolled Growth Rapid cell growth is not the same as malignancy. We all experience two normal situations in which our body tissues grow much more rapidly than they usually do. We grow from a single cell to a perfectly formed human being in nine months. Then we grow into a normal-sized adult human being over the next sixteen years or so. In addition, when we are injured and need rapid repair, restoration, and replacement of damaged tissues, our bodies can produce many new cells in a very short time.

When either of these processes—growth or healing—is completed, a set of genes tells the body that it is time to “switch off.” We don’t continue growing throughout our lives, and the scar we have after a cut has healed remains just that—a scar. Those are the rules.

But a cancer cell doesn’t obey the rules. The change in its genetic code makes it “forget” to stop growing. Once growth is turned on, cancer cells continue to divide in an uncontrolled way. It’s as though you set the thermostat in your house for a certain temperature, but no matter how hot your house gets, the furnace keeps running. No matter what you do to turn it off, it produces heat as if it had a mind of its own.

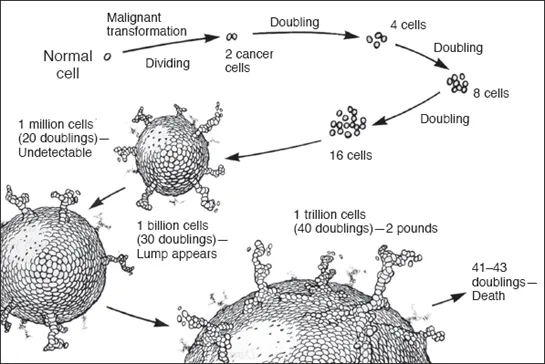

The malignant transformation of a normal cell and subsequent doublings. After twenty doublings (1 million cancer cells), the cancer is still too small to detect.

Doubling Times Cancer starts with one abnormal cell. That cell becomes two abnormal cells that become four abnormal cells and so on. Cells divide at various rates, called doubling times. Fast-growing cancers may double over one to four weeks; slower-growing cancers may double over two to six months. It may take up to five years for the duplication process to happen twenty times. By then, the tumor may contain a million cells yet still be only the size of a pinhead.

So there is a “silent” period after the cancer has started to grow. There is no lump or mass. It’s too small to be detected by any means now known. What is not commonly appreciated is that the silent period is considerably longer than the period when we do know a tumor is present.

After many months, usually years, the doubling process has occurred thirty times or so. By then, the lump may have reached a size that can be felt, seen on an X-ray, or cause pressure symptoms such as pain or bleeding. To be able to see a tumor on an X-ray, it usually has to be about half an inch (1 cm) in diameter. At that stage, it will contain about 1 billion cells. When it is smaller, X-ray imaging techniques are not usually sensitive enough to detect it, although some newer imaging methods—especially computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—may sometimes detect such small tumors. Blood tests called tumor markers may be able to detect tiny cancers that are not visible on X-ray or MRI examination, for example, PSA for prostate cancer (see chapter 2, “How Cancer Is Diagnosed”).

Benign and Malignant Tumors Tumors are not always malignant. Benign tumors can appear in any part of the body. Many of us have them—freckles, moles, fatty lumps in the skin—but they don’t cause any problems except (sometimes) cosmetic ones. They can be removed or left alone. However they are treated, they stay in one place. They do not invade or destroy surrounding tissues.

Malignant tumors, on the other hand, have two significant characteristics:

• They have no “wall” or clear-cut border. They put down roots and directly invade surrounding tissues.

• They have the ability to spread to other parts of the body. Bits of malignant cells fall off the tumor, then travel like seeds to other tissues, where they land and start similar growths. Fortunately, not all the many thousands of cancer cells that break off a tumor find a place to take root. Most die like seeds that go unplanted.

This spreading of cancer is called metastasis. And doctors are always concerned about whether the cancer has metastasized during the silent period. If it has, then the migrating cancer cells have begun to go through their own silent period. They, too, are too small to detect for many months or years.

Almost all cancers share these two properties, although cancers arising in various organs tend to behave differently. They spread to different parts of the body. They grow in very specific ways that are characteristic of that cancer. The consequence is that there is a specific method of diagnosis, staging, and treatment for each kind of cancer. One set of principles governs diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer, for example, while the rules for lung or colon cancer are just as complex but somewhat different.

What Causes Cancer

Although cancer is usually thought of as one disease, it is in fact more than 200 different diseases. For many of these cancers, no definite cause is known. There is no one single cause. In fact, cancer remains something of a mystery. But the clues we have discovered from research are greatly increasing our understanding.

The Roles of Oncogenes and Tumor Suppressor Genes One of the most exciting and important developments has been the discovery that some normal genes may be transformed into genes that promote the growth of cancer. These have been called oncogenes, the prefix onco- meaning tumor. This discovery has led to much research, better understanding of how cancer develops, and insights into methods of prevention, detection, and treatment.

Conversely, there is another set of genes called tumor suppressor genes, whose normal function is to help control cell growth. If tumor suppressor genes don’t do their job properly or are missing altogether, the cancer-producing action of an oncogene may not be suppressed and cells may turn cancerous as a result (see chapter 44, “Investigational Anticancer Drugs”).

The Implications for Screening All this new information raises the possibility that we may soon be able to test individuals—for example, with a blood test—to discover whether a specific oncogene is present and if the suppressor gene is defective or absent. The presence of certain oncogenes may even give us information about how likely it is that a cancer will spread. We may soon be able to identify people with a higher risk for cancer and possibly carry out other intensive detection and screening methods. Techniques for testing for oncogenes have recently been developed and are beginning to be available for general use. This new knowledge is already used in the study of familial (inherited) polyps of the colon and for familial breast cancer (see chapter 42, “The Impact of Research on the Cancer Problem: Looking Back, Moving Forward” and chapter 46, “Genetic Risk Assessment and Counseling,” for additional screening information).

How the Process Works There are approximately 20,000 to 25,000 genes within a human cell, only a small fraction of which regulate cell growth or division. It is now also thought that we all carry normal cells that contain oncogenes in the chromosomes, but that these oncogenes are never activated. They simply lie dormant throughout our lives.

In other cases, a mutation may occur because of some assault on the cell structure. Some stimulus or chemical agent turns on a “switch,” several oncogenes are activated, and they set to work together to transform a normal cell into a cancer cell. This is thought to be at least a two-step process. First, the DNA must go through an initial change that makes the cell receptive. Then a subsequent change or set of changes in the DNA transforms the receptive cell into a tumor cell.

The big question is, what causes these changes in cellular DNA in the first place? There are several theories. One focuses on viruses, which can insert their own DNA into a cell’s DNA and make the cell produce more virus-containing cells. Viruses may insert a viral oncogene or they might simply act as a random mutating agent.

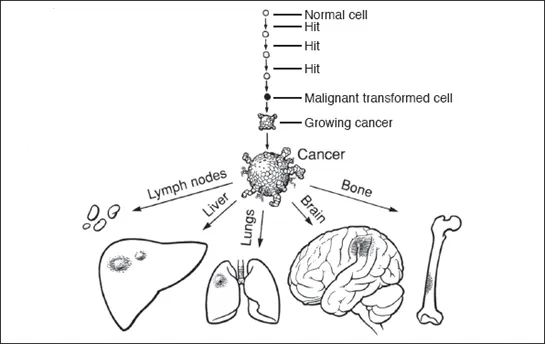

There is also some evidence that an assault by a “single carcinogenic bullet” hitting the cell at just the right spot can make a cell become cancerous. But the alternate theory that has gained a lot of support focuses on multiple “hits.”

After two or more “hits,” a transformed malignant cell grows into a lump we call cancer. Cells may eventually break off and spread (metastasize) via lymph vessels or blood vessels.

The Multiple Hit Theory According to this theory, all cancers arise from at least two changes or “hits” to the genes in the cell. Alfred G. Knudson, a cancer geneticist, developed his “two-hit” hypothesis in 1971 using hereditary retinoblastoma as a model. He postulated that patients who inherited one copy of a damaged gene (eventually discovered to be a tumor suppressor gene called RB) were at risk for developing this rare type of eye tumor, occurring mostly in children. That one bad copy alone was not enough to cause cancer; however, if a second hit to (or loss of) the good copy in the gene pair occurred sometime after birth, retinoblastoma would result.

Most cancers do not fall into this direct hereditary pattern and require multiple “hits” to various genes that build up and interact over time. These “hits” may come from chemical or foreign substances that cause cancer, called carcinogens. These initiate the cancer process. Or the hits may be promoters that accelerate the growth of abnormal cells. Critical factors are the number and types of hits, their frequency, and their intensity. Eventually, a breaking point is reached and cancerous growth is switched on.

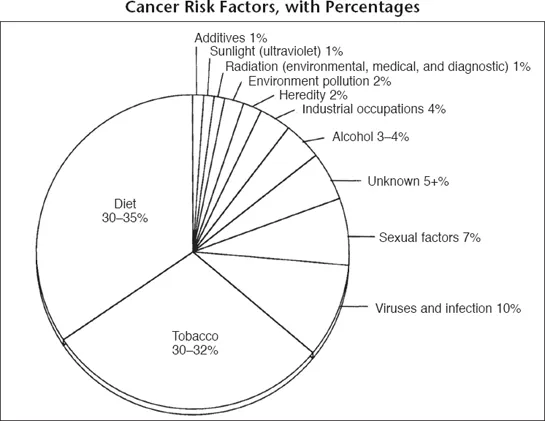

Initiators include

• Tobacco and tobacco smoke carcinogens. Lung cancer was a rare disease before cigarette smoking became widespread.

• X-rays and exposure to ionizing radiation. It is well known that there is an increased incidence of leukemia among atomic bomb survivors. This same increase was noted in radiologists, the doctors who specialize in the use of X-rays, years ago. It should be pointed out that the average diagnostic use of X-rays does not increase the chance of getting cancer enough to rule out their use as a valuable health care tool. The risk of not having an X-ray may far outweigh the risk of cancer being caused by the use of X-rays for diagnosis. Used properly, X-rays are of great benefit in finding cancer at an early, curable stage.

• Certain hormones and drugs, such as DES (diethylstilbestrol), some estrogens (female hormones), and some immunosuppressive drugs.

• Excessive exposure to sunlight.

• Industrial agents or toxic substances in the environment, such as asbestos, coal tar products, benzene, cadmium, uranium, and nickel.

• Dietary factors, such as high-fat and low-fiber diets, or carcinogens within food products or those created by the cooking process (see chapter 23, “Maintaining Good Nutrition”).

• Obesity.

• Sexual practices, including the age of a woman when she first has intercourse and first becomes pregnant. Certain sexually transmitted viruses can cause cancers, and the risk of catching one of these viruses increases with unprotected sexual contact and with the number of sexual partners. This is particularly true for AIDS-related cancers such as Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Promoters include

• Alcohol, which is a factor in 4 percent of cancers, mainly in cancers of the head and neck and the liver.

• Stress, which may weaken the immune system. Stress unfortunately relieved all too often with cigarettes, alcohol, rich food, and drugs.

Miscellaneous factors include

• Heredity.

• Weaknesses of the immune system, such as in transplant patients.

When two or more hits are combined—tobacco smoke and asbestos exposure, or cigarette smoking and alcohol, for example—the chance of getting cancer is not the sum of the individual risks. Rather, the chances are multiplied. Cancer is an additive process with many different hits occurring and interacting over many, many years.

What it comes down to is that the risk of developing cancer depends on

• who you are (genetic makeup),

• where you live (environmental and occupational exposures to carcinogens), and

• how you live (personal lifestyle).

Now that so many factors in our daily lives that affect the risk of getting cancer can be identified, cancer risk assessment has become increasingly vital to our continued good health. Risk assessment screening of apparently healthy people is now used in many cancer centers (see chapter 46, “Genetic Risk Assessment and Counseling”).

How Cancer Spreads

It is possible for tumors to start to grow in several places simultaneously, though this is unusual. They usually start to grow at a single site, called the primary site. So if ...