eBook - ePub

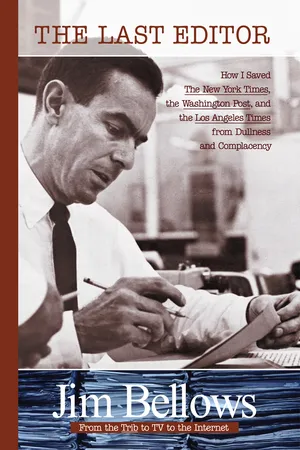

The Last Editor

How I Saved the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times from Dullness and Complacency

- 383 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Last Editor

How I Saved the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times from Dullness and Complacency

About this book

The innovative newspaper editor chronicles his storied career in this memoir, featuring sidebars from the like of Tom Wolfe, Katherine Graham, and more.

The Last Editor is the memoir of Jim Bellows, the editor whose David-and-Goliath battles changed the face of the newspaper business. Bellows struggled to save major competitors of America's three most powerful newspapers: the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times. In doing so, he developed major talent from rough cuts and brought a new generation of writers to the mainstream press.

The Last Editor is a unique memoir of a man who loved a fight—highlighted with commentary from his colleagues in letters and sidebars from the biggest names in media. Sidebars from Tom Wolfe, Ben Bradlee, Art Buchwald, Katherine Graham, Mary McGrory, William Safire, just to name a few, and 16 pages of black-and-white photos, provide behind-the-scenes insights to the triumphs and controversies of the man who shaped the industry.

"This is a lively, engaging recollection of the glory days of newspapers with amusing stories of the fabled men and women of journalism at a time when many American cities supported at least two newspapers." — Booklist

The Last Editor is the memoir of Jim Bellows, the editor whose David-and-Goliath battles changed the face of the newspaper business. Bellows struggled to save major competitors of America's three most powerful newspapers: the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times. In doing so, he developed major talent from rough cuts and brought a new generation of writers to the mainstream press.

The Last Editor is a unique memoir of a man who loved a fight—highlighted with commentary from his colleagues in letters and sidebars from the biggest names in media. Sidebars from Tom Wolfe, Ben Bradlee, Art Buchwald, Katherine Graham, Mary McGrory, William Safire, just to name a few, and 16 pages of black-and-white photos, provide behind-the-scenes insights to the triumphs and controversies of the man who shaped the industry.

"This is a lively, engaging recollection of the glory days of newspapers with amusing stories of the fabled men and women of journalism at a time when many American cities supported at least two newspapers." — Booklist

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Last Editor by Jim Bellows in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Journalist Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Jim Bellows loved a brawl. I think if a month went by without a brawl, he thought it was a pretty dull month.”

Tom Wolfe was recalling my relish at the literary controversy he landed us in with his articles on The New Yorker magazine.

It was 1965, the year that Norman Mailer marched on Washington, France left NATO, and the first U.S. combat troops landed in Vietnam, so it was not exactly an uneventful time. But the Tom Wolfe–New Yorker flap was still memorable. It was unsettling, potentially damaging, and the most fun I’d had in years.

I had set out to redesign the Sunday edition of the New York Herald Tribune for its publisher, John Hay “Jock” Whitney. Jock had made me editor of the paper and I was trying to create a lively alternative to the New York Times, New York’s venerable newspaper of record.

“Who says a good newspaper has to be dull?” we used to ask in our ads.

The centerpiece of our new Sunday edition was a new supplement called New York. It turned out to be so successful that it outlived the newspaper as the independent New York magazine. It contrasted nicely with the Sunday Times Magazine, which in those days was a little dull. Times readers were accustomed to spending their weekends with articles like “Brazil: Colossus of the South.” Their covers featured pictures of an ox with a Cambodian native behind it pushing a plow.

The literary stars on our new magazine were a couple of extraordinary young men whom I had managed to bring aboard the paper. One of them was a sportswriter named Jimmy Breslin, whose book about the New York Mets’ abysmal season, called Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game?, had been published in 1963. I put Jimmy to work writing a sports column, but I sensed that he was wasted there—Jimmy Breslin had enormous potential. So I asked him to write about the city. And the rest, as they say, is history. Then he started to write for New York magazine as well.

The other star of the Trib’s new Sunday supplement was a young fellow named Tom Wolfe.

Tom had been working as a reporter on the paper, covering hard news for the main sections. I wanted articles that were readable stories, not just news reports. Not every reporter is able to write that way—but God knows, Tom Wolfe could do it. He could take the everyday fact and make you see it anew. He had met all the tests of a daily journalist regarding clarity and speech, but he had gone far beyond that.

William Shawn’s Hand-Delivered Letter to Jock Whitney

To be technical for a moment, I think that Tom Wolfe’s article on The New Yorker is false and libelous. But I’d rather not be technical.… I cannot believe that, as a man of known integrity and responsibility, you will allow it to reach your readers.… The question is whether you will stop the distribution of that issue of New York. I urge you to do so, for the sake of The New Yorker and for the sake of the Herald Tribune. In fact, I am convinced that the publication of that article will hurt you more than it will hurt me.… As the editor of a publication that tries always to be truthful, accurate, fair, and decent, I know exactly what Wolfe’s article is—a vicious, murderous attack on me and on the magazine I work for. It is a ruthless and reckless article; it is pure sensation-mongering. It is wholly without precedent in respectable American journalism.… If you do not [cancel the article] I can only conclude—since I know that you are a decent man—that you do not understand Wolfe’s words. For your sake, and for mine, and, in the long run, even for the sake of Tom Wolfe and his editor, Clay Felker (God help me for caring about them), I urge you to stop the distribution of that article.

Letter sent the Thursday before publication, April 11, 1965

Tom was a remarkable communicator of energy and grace. His prose rollicked along with unexpected words embedded in pages that were covered with a confetti of punctuation marks. If his prose was eye-catching, so was he—his trademark was a gleaming white suit.

It didn’t take editorial brilliance to put Tom Wolfe to work writing features for New York.

A Letter from J. D. Salinger to Jock Whitney

With the printing of the inaccurate and sub-collegiate and gleeful and unrelievedly poisonous article on William Shawn, the name of the Herald Tribune, and certainly your own will very likely never again stand for anything either respect-worthy or honorable

And since a magazine is only as good as its ideas, I brought aboard a young fellow named Clay Felker to edit New York. Felker was a font of them. He came over from Esquire, where he and Harold Hayes had battled for the top spot and Clay had lost. One of the reasons he lost may have been that he was lobbying his boss to do an article satirizing The New Yorker.

“When you can edit as good a magazine as The New Yorker, we’ll talk about it,” was the reply.

Great minds think alike. Tom Wolfe had the idea of doing a profile on William Shawn, the editor of The New Yorker. When Clay Felker suggested a sendup of the legendary magazine, Tom leaped at the idea. They agreed that The New Yorker—that great ornament of contemporary writing—had in fact become somewhat tedious.

E. B. White’s Letter to Jock Whitney

Tom Wolfe’s piece on William Shawn violated every rule of conduct I know anything about. It is sly, cruel, and to a large extent undocumented, and it has, I think, shocked everyone who knows what sort of person Shawn really is. I can’t imagine why you published it. The virtuosity of the writer makes it all the more contemptible, and to me, as I read it, the spectacle was of a man being dragged for no apparent reason at the end of a rope by a rider on horseback.

April 1965

Richard Rovere’s Letter to Jock Whitney

Physically and atmospherically The New Yorker office Tom Wolfe describes is a place I have never visited. The editor of the magazine described by him is a man I have never known. Unless I have lost all judgment and power of observation, the piece you published is as irresponsible as anything I have ever come upon outside the gutter press.

April 1965

The New Yorker had had its fun with New York magazine. Lillian Ross had written a piece for the Talk of the Town in a parody of Tom’s coruscating style. It was about a playground in Central Park and the main character was a young mother called Pam Muffin. Clay Felker was engaged at the time to the actress Pamela Tiffin. Well, they had had their fun. Now we would have ours.

Tom called up William Shawn and when he finally got him on the phone, told him he wanted to do a piece on The New Yorker for New York magazine, and he wanted to interview him.

“We have a policy at The New Yorker,” said Shawn coolly. “That is, if someone doesn’t want to be profiled, we drop it. I would like you to show me the same courtesy.”

Tom explained that it was, after all, The New Yorker’s fortieth anniversary, and Shawn was, after all, a famous figure in publishing. So Tom was going to do the piece.

As he set out to write the article, the first thing Tom realized was that you cannot write a parody of a dull magazine. Not for more than half a page.

“Once you get the joke, it gets duller than dull. It’s the Law of Parody.”

So Tom decided to change the tone completely. He set out to write it in the style of sensational tabloid journalism. Something on the order of the old Police Gazette.

“I thought, the wilder and crazier the hyperbole, the better,” said Tom. “I wanted to paint a room full of very proper people who had gone to sleep standing up.”

Tom was working in the satiric tradition established by The New Yorker itself. Back in the 1930s The New Yorker had done a savage sendup of Time magazine and its famous editor, Henry Luce.

Luce went through the roof. The New Yorker’s founding editor, Harold Ross, had sent a copy of the article to Luce ahead of time, and Luce went berserk. He confronted Ross in Ross’s apartment and threatened to throw him out of the window. Tom never dreamed that Shawn’s reaction would make Luce’s seem mild.

Tom Wolfe Replies and Pays Tribute

A lot of people are going to read the letters and wires by Richard Rovere, J. D. Salinger, Muriel Spark, E. B. White and Ved Mehta, five New Yorker writers, and compare their concepts and specific wording and say something about—you know?—funny coincidence or something like that. But that is unfair. These messages actually add up to a real tribute to one of The New Yorker’s great accomplishments: an atmosphere of Total Orgthink for many writers of disparate backgrounds and temperaments. First again… they are evidence, I think, of another important achievement of The New Yorker. Namely, this wealthy, powerful magazine has become a Culture-totem for bourgeois culturati everywhere. Its followers—marvelous!—react just like those of any other totem group when somebody suggests that their holy buffalo knuckle may not be holy after all. They scream like weenies over a wood fire.

April 25, 1965, in New York

Tom’s piece turned out to be very long, so we broke it into two parts. The first part was almost exclusively about William Shawn—his life, his mannerisms, and the atmosphere he had created at The New Yorker. It kidded the magazine’s offices, its customs, and its editorial procedures. Tom pictured the hallways filled with aged messengers bearing a blizzard of multicolored memos: “They have boys over there on the 19th and 20th floors, the editorial offices, practically caroming off each other—bonk old bison heads!—at the blind turns in the hallways because of the fantastic traffic in memos. They just call them boys. Boy, will you take this, please.… Actually, a lot of them are old men with starched collars with the points curling up a little, ‘big bunch’ ties, button-up sweaters and black basket-weave sack coats, and they are all over the place transporting these thousands of messages with their kindly elder bison shuffles shoop-shooping along.”

He called Shawn “The Colorfully Shy Man” and portrayed him as diffident, excessively polite, and soft-spoken. He pictured Shawn draped in layers of sweaters as he went pat-pat-patting through the corridors.

The first section was headlined: “TINY MUMMIES! The True Story of the Ruler of 43rd Street’s Land of the Walking Dead!”

New York was printed on Wednesday for the Trib’s Sunday edition. On Thursday, I sent a copy o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Résumé

- Introduction

- 1. Tom Wolfe and The New Yorker

- 2. Ben Bradlee and The Ear

- 3. The Klan, Mr. Hoover, and Me

- 4. The Maggot Also Rises

- 5. Early Mentors

- 6. The Shining Moment

- 7. Maggie Changed Me

- 8. Decline and Fall

- 9. East Is East and West Is West

- 10. Good Times, Bad Times

- 11. Joe Allbritton

- 12. Oh, Kay!

- 13. Mary Not Contrary

- 14. Citizen Bellows

- 15. Big Stories

- 16. E.T. and ABC

- 17. On to the Internet

- 18. USA Today and TV Guide

- 19. The Geezer and the Kids

- 20. Last Word, and the Towers

- Acknowledgments

- Photos

- About the Author