- 330 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Bizarre Careers of John R. Brinkley

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Bizarre Careers of John R. Brinkley by R. Alton Lee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2022Print ISBN

9780813195391, 9780813122328eBook ISBN

9780813195940

Humble Origins

THE APPALACHIAN MOUNTAIN AREA OF NORTH CARolina, into which the Brinkleys migrated during the colonial era, has a rugged terrain but a pleasant, mild climate. Observers have long described the area as a “make-do” land. The inhabitants, both Indian and white, had to become jacks-of-all-trades and make do with the meager resources the land provided. Its harsh nature made its people tough and independent-minded. In this environment, most mountain folk married each other and raised numerous children, continuing unabated a cycle of grinding poverty. The milieu imbued a chosen few with ambition; infrequently, one with good intelligence, lofty goals, and great resolve managed to escape to a life outside. Others remained trapped in the culture.

Little is known of the early Brinkleys except what John R. Brinkley revealed later in his official biography and from a few scattered sources. William Brinkley, John R.’s paternal grandfather, was one of the first of the family to migrate southward down the valleys from Virginia into this austere culture, settling near Charlotte, North Carolina, while his relatives moved to nearby Mecklenberg County. He was elected captain of the First Regiment of North Carolina Troops in the Revolutionary War and received the usual land grant following hostilities. One of William’s sons, John, became a mountain doctor, that is, one who “read” medicine with a doctor much like one read law with an attorney before entering the legal profession.1

Clement Wood’s official biography of John R. Brinkley avers that his father, this “doctor” John, attended Davidson College in Charlotte and received a degree. This is highly unlikely, however, as attending college in the antebellum South was expensive and confined largely to the plantation and urban aristocracy who could afford it, not poor mountain folk. The biography also notes that “he had an eye for comely girls,” a more convincing assertion given that William had John’s first marriage annulled because he was underage, and John outlived several other handsome wives. He had two daughters by his first legal wife, Sally Honeycut. The 1850 census lists John, his second wife, Sarah, age twenty, and daughters Martha and Naomi living in Yancey County, North Carolina. John married his third wife, Mary Buchanan, in Webster, then county seat of Jackson County. (It was this marriage that caused John R. Brinkley to believe he had a half-sister, the celebrated cartoonist “Nell” Buchanan, daughter of “Marguerite” Buchanan.) When Mary died, the roaming doctor moved to Tennessee but soon returned to North Carolina where he married Fanny Knight.2

Fanny, like some of John’s earlier wives, died of tuberculosis, or what the mountain people called the “white plague,” and his inability to save his wives from this scourge made him broody. He was a Methodist and these losses “brought him over nearer to God.” His first four wives died before North Carolina seceded from the Union. John opposed slavery, but loyalty to his state forced him to serve the South reluctantly as a medic during the War of the Rebellion. Twice wounded during the conflict, according to the authorized biography, “he walked palely out of the hospital at last, limping only a trifle, and went on with his tight-lipped healing of the sick, the maimed, the halt, the blind.”3

In 1870, when he was forty-two, Doctor John married Sarah Mingus in Sylva. When Sarah Mingus’s attractive, reddish-golden-haired, twenty-four-year-old niece with dancing blue eyes named Sarah Candace Burnett came to live with them, the family called the aunt “Sally” to avoid confusing the two Sarahs. On July 8, 1885, the niece took to bed in Beta, North Carolina, near Sylva, and delivered a baby boy. She named her son John Romulus Brinkley, John after his father (Sally’s husband), and Romulus for one of the legendary brothers nursed by a she-wolf who later founded Rome. When John R. was old enough to understand, his mother told him the story of Romulus and urged him to be a “builder” when he was a man. The Wood biography declares that when he was baptized as a Methodist, the preacher thought Romulus was a heathen name and changed it to Richard. Brinkley himself later admitted that his friends teased him about his name so much that he went to court and officially made it Richard after his “uncle,” the first John Richard Brinkley. Being a love child in this culture was not extremely rare but nevertheless posed a psychological handicap in the maturation of the individual.4

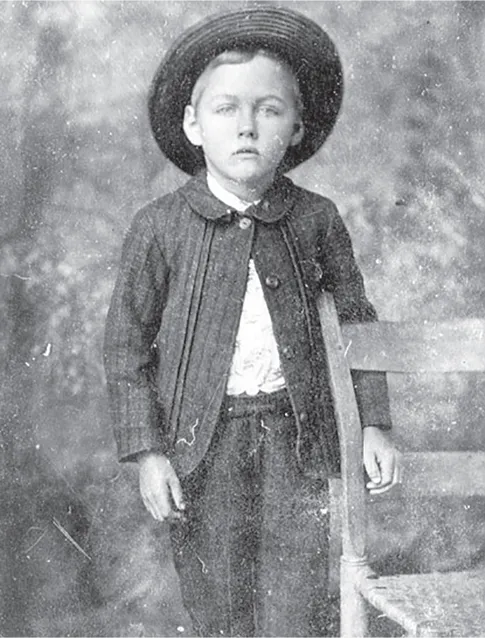

John Richard Brinkley II, as a boy. (Courtesy of the Kansas State Historical Society)

In the official biography, Brinkley says he did not remember his mother, yet Wood, to the contrary, recounts some vivid recollections of her. Wood described Brinkley’s infancy with her as not particularly happy, punctuated with the ever-present risk of tuberculosis contagion. She insisted he sleep with her, over the father’s objections. During a particularly harsh winter, she developed pneumonia, from which she never fully recovered. This eventually evolved into the “white scourge.” Night after night the boy, called Johnnie during his youth, awoke to her coughing and vomiting, the sheets damp with her perspiration. Believing she did not have long to live, she pushed herself to the limit, teaching the boy good table manners and the Lord’s Prayer—a difficult task as the little fellow was three years old before he could speak coherent words. She took him to all nearby religious revivals, and Johnnie recalled one particular meeting where he caught chicken pox. The hymns, the emotionalism of the “saved,” and the immersion of those baptized made a deep impression on the youngster. As an adult, Brinkley consistently demonstrated a strong piety in public and was very conversant with the Bible.

The Wood biography describes a dramatic and piteous deathbed scene with his mother when he was five.

In a feeble voice the dying mother called her one child to her bedside. He stared with awed round eyes at her emaciated body, hardly more than skin and bones; he leaned closer to catch the racked whisper that was all she could utter. There was a rattling in her throat; he had been told that this was the death rattle. Her eyes were on the mouldy [sic] plank ceiling; the little son knew that she could see through it to the unseen glories of the New Jerusalem. One emaciated arm came out, the fingers clutching at the counterpane, before they found the tiny son. She had to leave him, she said. She had prayed a lot about it, she said; because she was so anxious about his future. An angel had come to her in the night she said, who had told her that her own aunt would raise him, that he would grow up to be a great and useful man. There were tears trembling in her eyes, and Johnnie wondered why they didn’t fall. She brought out the other emaciated arm and looked again toward the ceiling. Feebly she tried to clap her hands. Her eyes opened for a choked shout. ‘Kiss me, Johnnie.’ And she had gone.

They buried her on a hill at the Lovedale Baptist Church cemetery outside of Sylva. Years later John R. Brinkley marked the site with a granite angel. The inscription reads: “In memory of my mother Sarah Candace Burnett, June 17, 1859, April 23, 1891. J.R. Brinkley, M.D.”5

Sarah T. Brinkley, or Aunt Sally, and John Richard Brinkley, whom the boy called “father,” raised the youngster. The family moved to East LaPorte where the father, who had become a minister in addition to his medical work, was welcome, as doctors were everywhere in the mountains. Patients seldom had money to pay for his ministrations, but sometimes he would bring home a ham or a turkey or occasionally a bucket of honey or molasses. In addition, the Brinkleys had a potato patch, with both white and sweet potatoes. A cow furnished some milk for the boy as well as for making gravy. Doctor John’s pleasures included hunting with his dog, dining on his favorite dish of sweet potatoes and opossum, and enjoying a plug of chewing or “manufactured” tobacco, as he called it.

Grave site of Sarah Candace Burnett, Brinkley’s mother. (Courtesy of the Kansas State Historical Society)

Always he prayed before meals and upon leaving on a medical call. Everyone was expected to kneel and pray with him. On one such occasion, Johnnie watched his pet pigeons strutting and preening in the sunshine. Horrified, he saw a cat spring on one. The boy was too afraid of his father to interrupt the prayer, but afterward he killed the cat in retaliation. His father was strict with him but never used the traditional hickory stick, due to Aunt Sally’s interventions. John Richard Brinkley taught the boy a simple code: be honest and honorable; guard your good name; honor preachers and doctors as being especially blessed by God; defend justice and righteousness; keep the Sabbath holy; and remember that God is quick to punish wrongdoing. Yet despite the great age differential, he was kind to his son in his own way, making sure the boy was supplied with candy and oranges as well as a mouth-harp, which Johnnie enjoyed playing.

Even as a boy, it was clear Johnnie was mechanically minded, and he always had hammers and tools handy. He was good at mathematics and an avid reader. The wife of a local magistrate who loaned him books and magazines discovered he could remember things readily, with a talent that would later be termed a photographic memory.6 As Johnnie grew older he, like his father, enjoyed hunting coon, fox, opossum, and squirrel. The Tuckasegee River also provided many happy hours of entertainment. The twisting, narrow mountain stream eventually drains into the Tennessee. Near his home there was a deep hole, perfect for fishing, and a calm stretch of water where boys could swim. The relatively-mild climate was conducive to outdoor sports much of the year. Neighboring outhouses and barns drained into the river, forcing Johnnie to carry water for the house from a nearby spring. Coal oil was expensive at 20 cents a gallon, so he gathered pine knots for the fireplace to take the chill off the evening air and to provide light for his reading. At nights, he watched fascinated as his father mixed his medicines from native herbs and purchased patents, accumulating a good deal of mountain folk medicine through observation.7

When Johnnie was ten, his father became gravely ill. The old man suffered from chest pains and had difficulty passing water. He had hardly taken to his sick bed when Aunt Sally told him a man had come asking for his help. The mountaineer’s wife, twenty-six miles away, was in need of medical assistance. John hitched up his old mare and plowed a bit of ground where he planned later to plant some corn. He rested on the Sabbath, then Monday morning after saddling the mare rode off along the mountain passes and trails. He made it to the cabin, examined the woman, and gave her some medicine. While her family was eating supper, he sat in front of the fireplace, watching the glowing embers and chewing tobacco. He died while sitting there. Neighbor John Moody brought the body home in a wagon and they buried it in the Wike Graveyard on a hill in sight of the Brinkley house. Johnnie was thrilled with being the center of attention as he rode on the funeral wagon, but was devastated by the solemnity and finality of the occasion. His mother was gone, and now his father. He vowed that he would hurry and grow up to become a doctor like his father, healing people so they would not die.8

Thaddeas Clingman Bryson, who grew up with Johnnie, recalled that his father had given John Richard Brinkley the use of a house along with a few acres for taking care of the Bryson family medical needs. Bryson now let the two survivors remain on this meager homestead. Aunt Sally could earn $3 for midwifing, providing perhaps $20 a year to purchase the few necessities to survive. They ate large amounts of cornbread and turnip greens, and Brinkley later said that if they had some molasses to sop up with the cornbread, they “had a feast.” They were not “poor as church mice,” however, as he tried to convince his radio audiences years later. Almost everyone they knew, except the Wikes, were impoverished mountain folk like themselves.

John recalled taking the old mare “over to Nigger Dave Rogers, and hitch[ing] her to the old man’s tanbark mill, and grind[ing] bark for him all day, to receive a gallon of molasses in return. Corn pone, milk, and molasses; it was a feast while it lasted.” But a day’s work for a gallon of molasses! When Aunt Sally was away on “baby cases,” Mrs. Amanda Jackson took care of him. This happened so frequently that he came to regard her as another mother. Four decades later he recalled her fondly and, when he discovered she had skin cancer on her face, offered to pay her expenses to travel to Little Rock to be treated by his friend, Dr. L.L. Marshall.9

Meanwhile, well liked by playmates, Johnnie was growing and observing and learning. He was a small boy for his age, but physically quick, fast to learn, and somewhat of a daredevil, friends remembered. Bryson recalled him as a bright young fellow who loved to play around Felix Leatherwood’s general merchandise store. There were always oldsters there engaged in checkers or pitching horseshoes. An observant, quick-witted youngster could absorb much by listening to their stories.10

He learned that the left hind leg of a rabbit killed in a cemetery and carried in the right hip pocket brought good fortune. Lacking this scarce omen, possessing a buckeye was also lucky; having both, of course, doubled the possibilities of good fate. Along with these charms, the chap had his boyhood dreams. “He was to be a doctor; that much was determined. . . . [H]is heroes [were] Abraham Lincoln, Thomas A Edison, William McKinley.” He fantasized about “freeing the slaves,” “illuminating the world,” or “facing an assassin’s bullet” like his heroes. He also dreamt of “healing the sick” and, as all poor boys imagine, of becoming rich.11

Johnnie attended the local school, held three or four months during the winter in a one-room log house. It was three miles from his home, and he later recounted the usual story of walking there barefoot in the snow, uphill both ways. In cold weather, he wrapped his feet in gunny sacks. The school was ungraded, which was normal for the time, and each child was expected to master as many subjects as possible during the brief terms. The teacher was paid $15 per month, plus free boarding with various families. This low remuneration resulted in inadequate pedagogues, and usually there was an annual turnover when the teacher found a better position.

When it was time for him to begin school, someone told Johnnie that the teacher enjoyed cutting off the ears of little boys. When she first came to call, unfortunately, she carried a large pair of scissors in her sewing bag. Johnnie refused to go to school that term. The next year Aun...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Picture

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. Humble Origins

- 2. Toggenberg Goats

- 3. Radio Advertising

- 4. Beset by Enemies

- 5. Brinkleyism

- 6. Hands Across the Border

- 7. The Old Cocklebur

- 8. Decline and Fall

- 9. Postscript

- 10. Conclusions

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Sources

- Index