![]()

Chapter I

Armstrong’s and the Period’s Origins

When questioned about the possible relationship or cross influences between Harlem Renaissance writers, artists, and musicians, a college professor said that any interactions and consequential inspirational art was minimal at best. He surmised that the Harlem Renaissance writers were merely imitating French impressionists, and the canon they produced was subpar. This research challenges that point of view through exploration of the influence of one of the period’s seminal performing artists, Louis Armstrong. To this end, this research will show the interrelationships and cross influences of the period’s literary, visual, and performing artists as well as the prevailing political and philosophical thoughts.

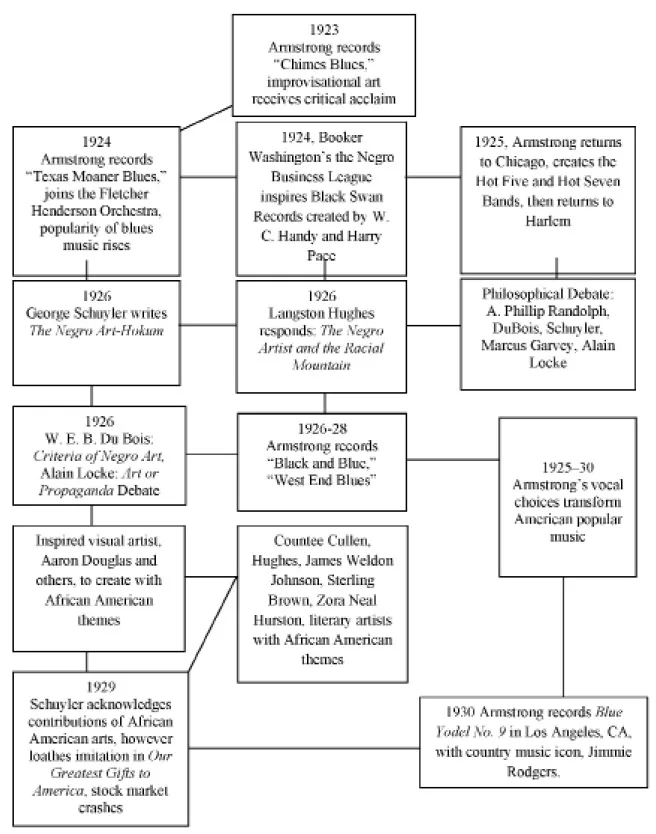

Armstrong’s improvisational choices helped ignite a variety of artistic activities during the period known as the Harlem Renaissance. In addition to the interrelatedness of Louis Armstrong’s creative decisions and the period’s literary and visual arts, this research examines the impact of Armstrong’s art and blues music on the political and philosophical debate during the Harlem Renaissance. A successful exploration into Armstrong’s and subsequently the period’s art, political, and philosophical entities requires one to examine the sources of the musician’s unique culture in New Orleans. The exploration will thus include the area’s West African approaches to making music in Congo Square, as well as the European musical influences, and the ebb and flow of racial relations that affected Armstrong’s life and choices. The reader will note such activity in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Louis Armstrong’s artistic contributions and interrelated artistic, political, and philosophical events, 1923–1930

Armstrong’s improvisational art, particularly his approach to blues music, was a significant contributor to the rise in the art’s popularity. Indeed, the performing art served as the subject or inspiration for much of the period’s literary and visual arts. Artistic contributions, though in various mediums, were interrelated. Not unlike other cultural or artistic eras, the Harlem Renaissance artists were aware of each other’s works. In various mediums, visual artists Aaron Douglas and Archibald Motley (among others) used blues music, and the ambiance created in some of the performing art’s Harlem venues as its themes. Subsequent chapters in this research will explore the use of blues music as the subject of poetic creations of some of the period’s important literary artists. They include, among others, Langston Hughes, Sterling Brown, and James Weldon Johnson. Philosophically, George Schuyler, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Alain Locke contributed to the debate as to the existence, purpose, and quality of the period’s art. These cultural matters were simultaneous with Louis Armstrong’s contributions to the period. Specifically, his initial foray with Joe “King” Oliver on “Chimes Blues,” collaboration with Bessie Smith on W.C. Handy’s composition “St. Louis Blues,” recordings of “Black and Blue,” and the seminal “West End Blues.”

Armstrong and the period’s art were not coincidental, unrelated events, but an evolvement of creativity spurred by the desire to express pride in the historical and cultural contributions of Africa and African Americans to this country and the world. The former is evidenced in the admonitions of artistic works such as Carter G. Woodson’s The Mis-Education of the Negro, Langston Hughes’s I Too Am America, a short-lived but important publication by a collection of seminal literary artists titled Fire, and Alain Locke’s The New Negro among others. Armstrong’s improvisational art, particularly his approach to blues music, was a major contributor to the rise in the art’s popularity. The performing art served as an aquifer to much of the period’s literary and visual arts. Artistic contributions, though in various mediums, were interrelated.

Contrary to the opinion of the professor, the literary art of Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, and Zora Neal Hurston, among others, were not celebrated in the context of French imitators but were indicative of the creative energy present in Harlem during the third decade of the twentieth century. In separate camps, visual and performing artists too contributed to the period’s art. The genius was in their ability to speak to the soul and essence of the African American experience.

Early West African Cultural Influences in New Orleans and Subsequently on Louis Armstrong’s and the Period’s Arts

The growing popularity of jazz and blues music during the third decade of the twentieth century, as well as the emergence of the period known as the Harlem Renaissance, did not take place in a cultural vacuum. The visual, performing, and literary arts produced during the period embraced African American mores and folkways. Therefore, it is necessary to explore Louis Armstrong’s contributions to the period in a historical context. This research explores some of the vestiges of West African history that influenced the music and cultural behaviors of the New Orleans enslaved population. One discovers (when placed in a historical context) that Armstrong’s art is partly a result of the performing arts’ practices during the decades before and after the Civil War. They include vestiges of West African music in an area called Congo Square and its subsequent influence on the cultural behaviors of the city’s people of color. European performing arts genres were equally influential as the city (during the nineteenth century) was home to two opera houses, while formal balls were prevalent, often employing Black musicians. Their employment was testimony to a musical versatility necessary to satisfy employers whose refined palates were nurtured by life in arguably America’s most musical city. Indeed, the documented behaviors and resulting rituals cultivated a cultural uniqueness that influenced the city’s early jazz pioneers and, subsequently, Louis Armstrong.

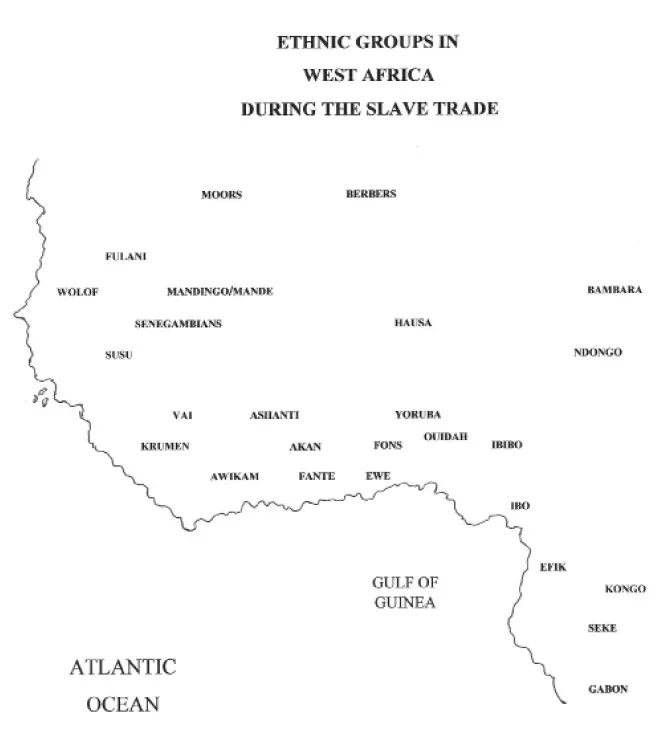

Though the enslaved that congregated in Congo Square may have been generations removed from their ancestors’ native land, evidence shows that they made every effort to recall the cultural significance and purpose in their weekly gatherings. More importantly, and pertinent to the Harlem Renaissance, documentation exits of West African historical and cultural contributions to world civilization. The contributions manifested themselves in the customs and cultural behaviors practiced by the enslaved and their posterity. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a careful (though brief, as attention to the broader subject demands such) exploration of the West African sources and how the New Orleans artistic diaspora shared it with the world, to fully comprehend the roots of the Harlem Renaissance’s performing arts.

African historians Cheikh Ante Diop, Al Bakri, and Ivan Van Sertima, in various research publications, detailed the cultural and political atmosphere in West Africa. Notably, the authors examined and published historical data about the peoples of Mali, Songhay, and Ghanaian empires from the tenth to nineteenth centuries. Diop especially noted the pre- and post-Islamic influences on West African culture, particularly music, which had a significant bearing on the music heard in Congo Square. The cultural lineage from West Africa to the enslaved diaspora in Congo Square becomes clear after careful exploration. Significantly, twelve of the first thirteen slave ships that arrived in Louisiana came from the Senegambia region in West Africa. France endorsed the enterprise under the auspices of the Company of the Indies. To this end, the earliest enslaved Africans brought to Louisiana in 1719 and 1743 were Senegambians, Mande, and Wolof from the Upper Guinea region, and from Ouidah. From the Lower Guinea region, the Ndongo and Kongo peoples were too enslaved and brought to Louisiana. The diverse grou...