![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Daughter of the War in the Desert

If Kurdistan was a country, it would be one of the most populous states in the Middle East, with thirty million people scattered between Iran, Iraq, Syria, Turkey and Azerbaijan. This is just the official toll, the real number is believed to be as many as fifty million. Turkey and Iran refuse to acknowledge their Kurdish populations, and therefore don’t count correctly the number of Kurds living within their borders, so it’s hard to know for sure how many we are.

My family was originally from the eastern part of Kurdistan, in the western part of Iran, which we Kurds call ‘Rojhelat’, meaning sunrise. In the YPG, our area in northern Syria is the western part of Kurdistan and we call it ‘Rojava’, meaning sundown. In Kurdish we also use the words Rojhelat for east, and Rojava for west. Bakur, our northern area, means ‘north’ in our language, and geographically is situated in south-east Turkey. Bashur, our southern area, is in the northern part of Iraq and we use this word for south.

Most Kurds speak Kermanji, which is spoken in Bakur and Rojava. Some Bakur Kurds still speak the original Kermanji, called Zazaki, but also different dialects, such as Sorani, Badini, Feyli, Kalhuri and Hawramani, which are also spoken in Rojhelat. Originally my family spoke Kalhuri, but now we speak Sorani or a kind of pidgin-mixture of both. Because of the different dialects, it’s pretty common for Kurds to struggle to understand each other.

My grandparents are both children of the Mahabad Republic, the first and only independent state declared by the Kurds in January 1946, and destroyed by the Iranian regime in December that same year. Along with their parents, my grandparents supported the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI) when it was formed the year before. As the first Kurdish armed movement to become an official political party, the PDKI was established to promote democracy, social justice and gender equality, rejecting monarchy, theocracy and autocracy. Supported by the Soviet Union, the PDKI ran our republic for the five years leading up to the official declaration in 1946. The PDKI continue to train Peshmerga (our word for fighter, which translates as ‘one who stands in front of death’) to defend Rojhelat from the Islamic regime of Iran. After our nation was destroyed by the Shah of Iran in December 1946, many PDKI leaders were executed, but the party remained in existence. My grandfathers met while my family was still inside Iran, as they both served as Peshmerga fighting against the regime of the Shah in 1967. This is how my mother and father would later come to know each other.

My mother’s family farmed the mountains outside Kermanshah in the countryside of Serpeli-Zahab, which is right on the border with Iraq. Even within this small region there are several dialects: Kermanshani, Kalhuri, Sorani and Feyli. Working as an informal cooperative, her family produced food and reared animals to trade. My mother didn’t go to school in Iran or Iraq – her education comes from Denmark. My father believes the lack of women’s education is one of the reasons why Kurdistan still doesn’t have its own nation state, and he was educated very well by his family along with his brothers in Iran, but his studies were cut short by the war. All of the sons in his family, just like my mother’s, became Peshmerga as soon as they were old enough. This led to several relatives and friends being executed and killed inside Iran, so my father had to leave.

While my father’s family is mainly Sunni Muslim, one of his brothers was a Christian – which didn’t bother his family, but made him even more of a target for Iran’s Revolutionary Guards. He would sneak around to attend services run by the American Church groups that existed inside Iran. He was abducted many times, but he could not confess to crimes that he had not done, so his captors would eventually grow tired and release him. They tortured him because he was a Kurd, first and foremost, but also due to his belief in a Christian God and their belief that he was an agent of ‘the Great Satan’ – America. Kurds are mainly Sunni Muslims, and the regime remains a Shia theocracy. To be a Kurd in Iran at the time – male or female – was to be an enemy of the state, and to be Sunni inside Iran still remains very difficult.

My mother’s father was a Peshmerga commander and captain for the former president of Bashur, Mala Mustafa Barzani. He was also a farmer, who would take animals to trade in the markets inside the old souks of Kermanshah, our city in Iran. Our area, also called Kermanshah, has the highest Kurdish population in Iran and extends far beyond the city, almost from the city of Hamadan towards Tehran, and to the border with Iraq on the other side. It is home to Shia and Sunni Muslims as well as Circassians and Christians, which makes it unique as a region inside Iran. Although the city suffered in the Iran–Iraq wars during the 1980s, the people of Kermanshah are relatively open-minded for the Middle East. Different cultures live peacefully together, as they are all threatened by the regime. Young people especially look west for their hopes for the future – devouring American media, fashion and popular culture – or at least the ones I know do.

My mother thinks she was eleven when her family fled on foot from Iran into Iraq. As she never went to school or learned to count, she isn’t even sure when she was born: she thinks it was 1971. She has a very conservative view of how a family, and especially women, should be. She married my father when she was fourteen years old, in a match arranged by my grandfathers, who met again when their families were both living in the Al-Tash camp in Ramadi, after they fled Iran.

Marrying young remains very normal in my culture, and in my family. Back in my mother’s day – which is not so long ago really, as she is not yet fifty – girls would be married as soon as they had their first period. My mum used to say it was for our own sake, because waiting longer would mean a girl was more likely to have physical contact with a man, which, in my mother’s opinion, is a fate worse than death. As our mother, it is up to her to police our sexuality and ensure that we protect the family name until we are married. The younger this happens, the better. I am twenty-five now, and my not being married is a source of discomfort for my family. We talk a lot about girls in our community, and as a girl gets older and remains unmarried, rumours about her start. People look down on her, and talk badly of her mother for not being ‘woman enough’ to raise girls properly. Everything we do right, our father takes the credit for, but for everything we do wrong, our mother takes the blame.

A woman being independent, or living alone, is treated suspiciously by the community. After a certain age – normally late teens or very early twenties – marriage prospects for girls like me shrink, and offers of marriage start coming in from older, divorced or disabled men; those with lower status. If you are unmarried after twenty-five, in the community I grew up in, most likely your fate is to stay unmarried or to become a man’s second wife or mistress. In the Islamic world it’s estimated that one in every five men practises polygamy, and sadly many men in Europe practise it, too. If, like me, you are not a virgin, your prospects are worse still.

In the 1980s, when my mother was growing up, the Iran– Iraq war was fought mainly in Kurdish areas, and villages all along the border were destroyed by Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist party soldiers, who suspected the villagers of being traitors to the Iraqi government, or loyal to Iran. Hussein was a dictator who fought against anyone who wasn’t a Ba’ath supporter. During the disaster of the wars, our neighbouring countries supported different Kurdish armed movements, and different tribes aligned with them in return for food, supplies, shelter and protection. This led to different Kurdish factions fighting each other, and although the conflict between Iran and Iraq eventually stopped, their wars against the Kurds never did. The Iraqi border with Iran became porous, as Iranian Kurds (from the PDKI) brought supplies over the mountain to fight against Saddam, and other Peshmerga fighters from Iraq (from the Kurdish Democratic Party, known as the PDK) used the borders to fight the regime of Iran. Many of the Kurds living near the border were nationalists against the Ba’ath party and Saddam, but were also opposed to the Islamic regime of Iran. My family, like many in the region, was against them both. Thousands of Kurds fled from Iraq into Iran, but going back to Iran, as supporters and members of the PDKI, was not an option for us.

My family name, Palani, has long been associated with the PDKI, and still is. After living in Balkan camp near Sulaimaniya in northern Iraq, both my father and my mother were moved, with their families, by an NGO to the Al-Tash camp near the desert in Ramadi, in the centre of the country. Some of my father’s family were moved south from Balkan to Halabja, and lived there from 1987 until the 1988 attacks.

On 16th March 1988 Saddam Hussein’s forces dropped chemical bombs on the city of Halabja, killing thousands of civilians. More than 5,000 people were poisoned that day, and many more died as a result of their injuries in the months and years that followed. It is the greatest crime ever inflicted on our community, and remains the biggest gas attack ever launched against a civilian area. Halabja was not the only gas attack against members of my family, but it was the most personally devastating, as many of our immediate relatives died: thirty family members in all. My maternal grandmother lost her entire family. We have only one picture of my aunts who died, from when they were younger girls with my grandfather in Iran. We don’t have any pictures of their children or family, so I often wonder when I see the famous images of the attacks if the bodies of the children I am looking at are the remains of my relatives. I will never know.

My mother had me quite young, but before me she had my three brothers and one of my sisters. My mother had all her babies in Ramadi: six in total. Two years before I was born, in 1991, things became more difficult for my family, as we had taken part in another failed uprising against Saddam Hussein. My father worked as a pharmacist, but like all Peshmerga, he helped the American soldiers when the Iran–Iraq war turned into the Gulf War in 1990.

Working with the Americans was a political pivot for my grandparents, as the Soviet Union had previously been our allies supporting the Mahabad Republic, and we were now aligning with US forces; but, as Kurds, we are not afraid of making strategic alliances against our enemies. As Kurds, we are targeted by the countries within whose false borders we live: Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran; and by their strategic backers. After Halabja, Saddam Hussein was our common enemy and we got help from the USA to depose him.

My father speaks five languages, having benefited from his education in Iran under the Shah, and worked with the USA to help the soldiers with logistics, translation and supplies in Iraq. When the Americans originally came to Ramadi they had not expected conditions to be as desolate as they were, and they were forced to leave again so that they could plan properly for a bigger operation. My father managed supply routes for them and spent some time working as a translator. He speaks with an American accent when he talks English, as many Kurds do. The US soldiers would guard our camps so that Saddam’s soldiers couldn’t come in, and their combat medics would give basic treatments to those in dire need.

The Americans promised that a Kurdish region would be established in Iraq after Saddam fell, so naturally many Kurdish men joined up to secure this and to avenge our dead. But the Americans lost the Gulf War – they left in 1991 with Hussein still in power – and when they suddenly left Ramadi, our camps were attacked. We were on the retreating side and, as punishment for working with the Americans, we were again targeted by the regime. Around this time our camp in Ramadi suffered an attack, and my older brother Mariwan was killed due to the lack of medicine and treatment provided for our people from the hospital in Baghdad. Lots of our people died; from bad medicine, from no medicine, but mainly from the regime’s attacks.

My brother was two years old when he died and was buried in the desert along with the others who were killed. Neither my mother nor father talks about him. The trauma of his bloody death lives on in both their hearts, and my mother places this event as the moment their marriage began to disintegrate. I’m not sure. I’ve only really seen my mother hysterical once in my life, and it was when one of my two surviving older brothers got sick. She screamed at my father and said that if another of her sons died, she would go with them and he would be left with us. Mariwan was named after a Kurdish city in Rojhelat, but in our family everyone called him Rambo, because he was very big when he was born, with white skin and black hair. There was one old TV in the camp, where we would watch American films huddled together, and Rambo was everyone’s favourite show. Mariwan was supposed to grow up to be a warrior, like our father and grandfather.

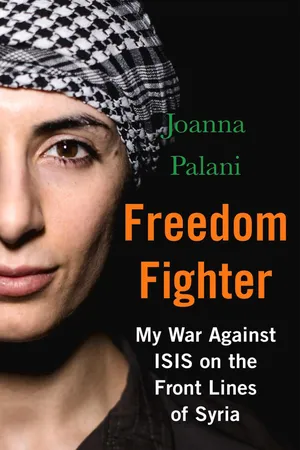

A few years after my brother died, on 22 February 1993, I was born. My mother said I arrived at first light on another freezing-cold day. I was named Hero Palani – a Kurdish name, but also after the Greek goddess Hera – by my father, but my beloved Christian uncle Jabbar changed my name to Joanna, which means ‘beautiful’ in Kurdish. I remember more from Ramadi than my siblings, but within our family there is endless debate over whether we actually remember events or just think we do, because we know the story behind the photograph. Old photographs are a particularly valuable commodity in my family: both my parents jealously guard pictures of their family and their childhoods in Iran, and then of ours in Iraq. There is a certain preciousness to our photographs; spread out as we are, and destroyed by such an array of enemies, these pictures are often the only evidence we have of our relatives and our past. In Kurdish culture we celebrate the group – the family, the community and the clan – instead of the individual, and the rules of the clan are the rules by which we live. The pictures of my family in Ramadi show us all huddled in a big tent. Inside, almost a whole wall of our tent is taken up with coloured blankets, and some of my earliest memories of Ramadi are playing on these blankets and looking up at the sky.

My father, uncle and I are the only ones who remember the Ramadi camp as it really was, for the rest of my family have these weirdly romantic memories of our lives there. I remember it as a dry and dirty place, without much food or water. I would accompany my older siblings and other relatives to dig for water in the sand. Because it’s in the desert, Ramadi scorches in the summer and freezes during the winter. We would be sent to bed with gloves and hats on inside our tents, and if we complained of a chill we would be allowed to sleep in between my mother and father, along with my youngest sister, who in my mind was permanently attached to my mother’s chest. I’ve never learned to sleep properly, and my memories of bedtime are of lying shivering in between my parents, or trying to find some relief from the oppressive heat. Many infants died from pneumonia and hypothermia in Kurdish camps around this time; it’s hard to know how many, as we are not the kind of community the regime was interested in recording, and we would never trust them to keep count accurately anyway. Because of the lack of medicine, vaccines and healthy food, my siblings and I suffered from malnutrition. We had those big stomachs you see on television, where the swelling was caused by not having enough protein in our diet – a condition known as kwashiorkor.

I was too young to go to school, so I stayed with my mother and my baby sister as our older brothers and sister went for lessons. They had to walk to school from our tent in single file, with one standing in front of the other with a branch, so that if they came across a landmine, only one of them would be killed. When my brother and sister went to school, my mother would sit in the front of our tent and fix her hair and inspect her face, using a tiny pocket mirror that she would hold up to the light. She would always become very annoyed if we got dirty, and once we were washed we were expected to stay clean for as long as possible. Water was a precious commodity, so we weren’t allowed to wash too frequently.

My older sister would collect sticks from ice-cream lollies from around the camp and we would transform them into dolls, and build them houses and furniture from the rubbish that we found in the sand. We had many cousins and family members across the camp, so we would sometimes spend the day or night with them in their tents or houses. Behind the tents the boys would play football, making a ball from different plastic bags fashioned together – the older boys managing to copy the stripes of a leather ball surprisingly well. The women built ovens to prepare the bread daily, and dug deep holes in the sand for water. Every night everyone would gather around the TV to watch the news. Although the camp had two entrances and exits, us Kurds shared with the Shia families, and we all lived together.

Saddam’s soldiers were called ‘the redheads’ because of the berets they wore as they stomped around our camp. After the Americans left, they would come in whenever they felt like it, and my aunt would tell us kids to run and hide inside our tents. Our Peshmerga had no weapons in the camps, so we had no choice but to agree to whatever the soldiers demanded. They of course targeted our women, raping them with absolutely no consequences to themselves. In the Middle East, most people consider a girl able to have sex as an adult after she has had her first period. A ‘woman’ is normally a married person who has had sex, whereas a ‘girl’ has not had sex. The redheads would take any girl they wished, and they did so often. The girl was sometimes taken away from her family and never seen again – trafficked into prostitution or killed – or was returned to her family after the rape, so that the family would be destroyed by the shame. Either way, the girl’s life was over. In a war created by men, the girls are sacrificed.

After the Americans had left, leaving the camp open to attack from Saddam, the military bases and medical hospitals all packed up and left; it was only the NGOs that remained. Suddenly everyone was trying to leave the camp, in case the redheads came back again. There was fear that the first bombardment was just a precursor to a second attack, and that they were planning to gas us alive. We had no gas masks of course, but my parents taught us how to cover our faces and ears with our clothing.

The United Nations helped my family apply for asylum to leave Ramadi, and suddenly, in 1996, we were told we were going to Denmark, as UN refugees. We got to leave more quickly than other families because of what had happened to Meriwan, but my aunt was not allowed to travel with us at the time. I remember three big buses coming to collect us and several other families who were going to Scandinavia. The women who were staying behind sobbed as we boarded the buses, and the crowd was so big that the bus driver got annoyed at everyone hugging each other through the open windows. My mother tells me that she held up me and my little sister at the back of the bus, so that my aunt could look at us one last time through the window, and then held me and cried into my coat until we arrived at the field where the plane was. She talks about our aunts a lot, and we remain close to them when we travel back to Kurdistan. Today I’m closer t...