![]()

1

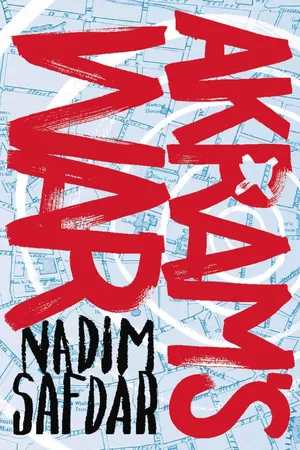

I am Akram Khan, formerly Sergeant Khan of the Queen’s Own Yeomanry, and in a short number of hours, at a place not far from here, loaded and enabled, I will submit.

My wife Azra sleeps in our bed, a white linen sheet pulled tightly around the bony geometry of her figure. Her thin hand, curled into a fist, is wrapped in the sheet, her wrist weighted with gold bangles. In profile, her nose is studded with a pinprick of gold. I lie next to her, every muscle contracted towards a knot in my gut, and although our bodies at their nearest point are merely an inch apart, I am careful not to touch her. I lie as though trapped, perfectly still under a shared sheet. When Allah wills it, and soon He will, it will be my time for eternal sleep, my conclusion. As I pass into the hereafter the brothers will wrap me in a shroud of linen, and they will chant the names of Allah as they lower my remains into the earth. And over my body they will heave a single slab of stone.

For Azra the membranous sheet is protection against my efforts to consummate our marriage. I have tried. For a time my hands were hopeful: brushing against her shoulders, playing with a loose strand of her hair, twisting it around a digit as tightly as I dared; when feeling bold my fingers would trace the bony contours of her spine. In the cold house, listening to the rain lash against the bedroom window and feeling lonelier than I imagined possible, again and again I would try.

The strength of my want surprised me. Even as I trembled, perspired, clutched myself to still my jerking muscles, the sensation felt decent. Later, shamed by her and branded a failure, a humiliation tempered only by the cumulative incantation of a thousand Bismillahs, I abandoned my earthly desires and accepted the inch or so between us. She snores lightly, contentedly, still a virgin.

She is not for me. Not in this life. I tell myself: I am saving my pleasures for when I am dead.

It is time to make ready, and carefully I swing my feet to the floor. A bullet fired from close range has left me with titanium and gristle for a knee joint. Below it I have no feeling, and I move awkwardly, trying not to wake her. I make it to the door and take one last look at Azra. She has turned away, her long black hair falling across the pillow, one knee bent up to her chest, stretching the sheet taut. By day my bedfellow covers herself in a black burqa that, save for a rectangular screen through which she sees, completely enfolds her body. She says the burqa is to conceal her from the lustful eyes of men. I say that her virtue is a strange game.

The narrow hallway is dark, and with the help of a walking stick that I leave by the door, I carefully place each step, keeping to the edges to avoid creaky floorboards. My fingertips brush against the wall for orientation and balance. I hear a faint rumble as the last train from Birmingham slows, ready for a last draw of breath as it pulls into Rowley Regis station, its great energy transmitting through the house.

The railway came first, then factories and workers’ houses, small damp houses like the one I have lived in my entire civilian life. In the early days the voice of our street was the echo of great steam-powered hammers and bubbling fires of molten steel, and to us this was regular and bucolic, as birdsong might have been for others. It was a disembodied noise, one I heard but could not see, shielded as it was by high perimeter walls. Children would assemble as the factory gates drew open at the changing of shifts, hoping that their fatigued and oil-stained fathers would buy them a pop on the short walk home. But more than that, we gathered for an opportunistic glimpse through a gap in the gates, of giant hammers and spitting fire.

The carpet is threadbare underfoot and the wall rough and crackly beneath my fingertips, and it startles me that there is knowledge here I have yet to acquire, and that the house has silently aged, sagged and worn. I hear a gentle sound of stretching bedsprings as my mother or father turns in their sleep. Reaching blindly into the room I pull at a light cord, then take a sideways stride into the loo and ease the door closed. A small extractor fan cut into the window picks up speed and settles into a constant rhythm. The overhead light blinks, casting the movement of my limbs in slow motion.

I look into the mirror on the small cabinet above the sink and clutch my beard. Abruptly the flicker flatlines to a thin fluorescent beam. My beard is thick and densely black. It has grown to just beyond the length of one fist and is immediately recognizable from a distance. It marks me as one who has rejected the vanity of the infidel. One who has chosen. I release the hot tap. Pipes rumble as though summoning strength from distant corners of the house. A jet of water issues, becoming scalding; as it meets the cold parabola of the sink it generates steam. I turn it off and watch it glut.

From the cabinet I select a small pair of scissors, a disposable razor and a can of shaving foam, placing each item on the porcelain ledge between the taps. I pinch at a tuft of beard and take a swipe at it with scissors – a sinful thing. Out in the street I hear a cat cry and then all is silent save for the mash of the scissor blades. Short clumps of hair collect on my palm stretched below. I whisper a short prayer, ‘Bismillah ir-Rahman ir-Rahim’, a consolation for my loss.

About prayer I am superstitious, and superstition is a magic not permitted to the believer. Although we are born perfect, few of us remain in that state, and it is enough to reach out, to strive, to hope for forgiveness. At night I leave a gap in the curtains, and the very moment I awaken, raising my head from the pillow, I catch a piece of morning sky and whisper, ‘Bismillah ir-Rahman ir-Rahim.’ It is like saying hello to Allah, and every new scene seems to warrant it. A thousand times a day, maybe more – tucking into breakfast, pulling my trousers over my bad knee, leaving the house, sidestepping a crack in the pavement, seeing someone I know or don’t know, putting a fruit to my nose, watching a bent old lady crossing the street, washing my hands or rubbing my sore knee. Remembering Allah lends a kindness to each scene, slows down our fast lives, so that even the little things are lived in a state of suspended grace. And the more I say the Bismillah, the more it seems necessary. It is instinctive, important. It reminds me of the vastness of I, a mobile dot under the spread diaphragm of a ceaseless heaven.

I snip carefully around the vermilion border of my lips where brown skin meets pink flesh. Between my fingertips the hair feels thick and wiry. It is densely black, glossy from the application of palm oil scented with sandalwood and something else, something eastern and exotic, an oud, a pleasant odour, something like night-blooming jasmine, a scent that keenly fills the air wherever a group of brothers assembles.

Brothers: drawn from distant corners of the world and merged in Cradley Heath. United beyond blood and flesh, the strongest of brotherhoods falling under the cast of Allah’s love. Brothers at the mosque, and afterwards brothers walking hand in hand and arm in arm, brothers brimming with excited thoughts as we repair to the Kashmiri Karahi House and Sweet Shop. Brothers who, before a word is said, upon the instructions of Brother Mustafa (our first-in-command) scan the sparsely furnished kebab shop, sweep memory for the slightest change in the walls, look underneath green plastic tables and chairs, patrol behind a counter at the far end, and unscrew, inspect and replace a solitary pendant light bulb.

Under a dim fluorescent light at the Karahi House the brothers and I (although I no longer wear three stripes, clearly I am second-in-command) feel safe. We talk about martyrdom and search each other’s eyes for the difference between doubt and sincerity.

‘What would it be like?’ Second-in-command.

‘Who will go first?’ First-in-command.

‘Will Allah greet us personally?’ That could be any one of the brothers, lightly swaying to a scene secured under clamped eyelids.

And, although no one will say it out loud, we are each picturing voluptuous houris, their bodies stretching against the slippery silk of the most exotic garments – and we each struggle to hide that thought from our brothers.

‘Boom. Boom.’ That’s Ali, the Karahi House proprietor. He is a joker and speaks carelessly as though to shame us. ‘I can see ladies dancing in your eyes.’ A spatula in one hand gesticulates lewdly while with the other he flips lamb chops on a sizzling grill. ‘Their feet, garlanded in silver anklets, dancing on your filthy souls.’ Oily spice fills the room.

Carefully I drop the hair into a plastic Ziploc bag retrieved from my pyjama pocket. The uneven crop of close-cut bristle now reveals something of my former face. I have a square jaw, full lips, and eyes a girl once described as gentle. When it mattered to me, I considered myself handsome. It flashes across my mind that before I shave it all off I could groom myself something fashionable. A goatee, perhaps? Just for a minute, to see what it would look like. But those thoughts are the diversions of Beelzebub, a temptation to infidelity, and to compensate I whisper a quick Bismillah. Staring into the mirror, I allow myself a small smile. A smile in recognition of the unfortunate fact that we can never be truly faithful to Allah, that within my weak mind there is still resistance, rebellion.

I shake my head vigorously as though it will scatter those thoughts, and with the razor I cut neat tracks into what remains of my beard, dispersing shaving foam thick with black hair under the running tap. The skin underneath is smooth and stretched taut like a canvas over my chin. Already I feel colder without the beard. My face itches and burns and I rub and press at it as though kneading dough, leaving behind short-lived, thumb-shaped welts. The image staring back at me is boyish: it is the vanity of the infidel and reminds me of my earlier self, of a time before belief in the one and true God. That there was a time before belief seems hardly possible, and I turn my eyes away.

I rub in a splash of Cologne, gritting my teeth as it stings. It has been a long time since I felt that particular pleasurable pain.

My gaze tilts upwards, squinting through a small rectangular window to the marbled black sky, imagining the hazy horizon, the join between sky and land that determines the end of the visible world. A scene that Allah will illuminate at dawn. ‘Bismillah ir-Rahman ir-Rahim.’

I concentrate my eyes into the distance, connecting with what I cannot see, the great invisible being just beyond. I am barely conscious that I am standing before Allah. I see through the clouds to a crescent moon. As I concentrate harder, I view a colourful scene of an orchard with round bushy trees of a wonderful brightness, the likes of which I have never before seen. Bulbous red pomegranates grow on the trees, and in the air is the scent of sandalwood and jasmine and roses. A stream flows across the foreground. On its golden waters glides a wooden barge propelled by a fisherman punting with a long pole. In the background, as though painted in, are the snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas, places colder and more isolated than man could ever stand. As I now look down, out from this dizzying height, a wind spurs like sharp knives at my face, and as my arms waver for balance I open my mouth for one final breath of thin, giddy air.

I feel a knot in my throat; my heart races and a surge of adrenaline makes my whole body shiver. Despite the coldness of the bathroom, strangely I feel warm. It takes all my control not to cry out loud.

And suddenly an ugly pain works my knee. A familiar antagonist that is worse between the hours of sunset and sunrise. The doctor assured me that all pain increases at night-time, but its eagerness surprises me. Sweating, I rest on the edge of the toilet seat and clutch at my artificial knee and hope that might banish the sensation that grips, like the branches of an electrical tree, the nerves above and below the wound.

When finally it eases, I pull down my pyjamas, letting them drop to my ankles. My cock I shield with one hand and, with the other, first trim the hair, snip and deposit. I adjust my position, but very carefully in case I reignite the pain, bending low to my task. I rub in a very thin layer of shaving foam and carefully guide the razor around the curves, pulling and tweaking at my anatomy, stretching the skin flat.

The razor, sealed into the Ziploc bag, I dispose of in a pedal bin under the sink. The shaving foam and scissors are replaced in the cupboard. It is better to return things to where they came from, always better.

Quietly I unlock the bathroom door, turn off the light and step into the hallway. It wasn’t as satisfying as I would have had it. I had imagined an overwhelming serenity, but it was more practical than that, and at times, shivering in the cold bathroom, I had wanted it to be over as quickly as p...