![]()

1

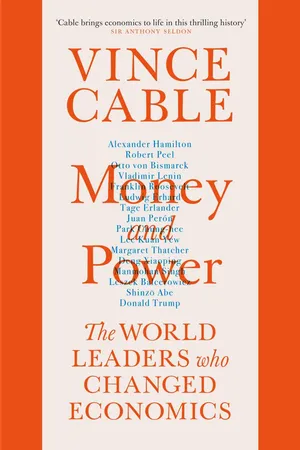

Hamilton: The Economic Founding Father

The closing decades of the eighteenth century were the first period in which recognizably modern political and economic ideas came to dominate. It witnessed the first stages of what would become the industrial revolution in the UK. The period also spans the American and French revolutions when ideas of ‘left’ and ‘right’ and liberalism and nationalism found full expression. It saw the publication of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776) building on the work of John Locke and David Hume. The book’s ideas helped to frame the debate around trade – and wider economic policy – for much of the next century and beyond; indeed, its legacy lives on today.

In the new United States, Alexander Hamilton (1755–1804) was at the centre of political and economic life: as a revolutionary soldier; then leading politician; as co-author of the US Constitution; and as economic policy maker and thinker (most prominently as George Washington’s Treasury Secretary). According to American economist Douglass North, as Washington’s Treasury Secretary, Hamilton was responsible for ‘the most important developments for subsequent growth in the economy… as [his policies] formed the monetary and fiscal underpinnings of the new nation. The first established a sound credit basis; the second was an important beginning of an elaborated capital market.’1 Hamilton set out the framework for America’s industrial revolution and private enterprise economy and for a system of trade protection to support manufacturing – widely copied elsewhere in the subsequent two centuries. His approach to economic policy was perhaps best summarized by his biographer Nathan Schachner, who noted that he had read and absorbed Adam Smith but had adapted his ideas to the particular needs of newly independent America.2 He also anticipated the future needs of a developing market economy for financing business and government. He established the pragmatic formula which has served most successful governments well in the US and beyond: he was an enthusiastic supporter of business and markets but also promoted strong government.

Hamilton attracted much attention for other reasons: his colourful upbringing amid the slave-owning communities of the Caribbean (and his own antipathy to slavery); his brilliant military record as a youthful aide-de-camp to Washington in the War of Independence; his role in framing the new American Constitution and the party system of the fledgling democracy; his contributions as a poet, essayist, lawyer, financier and businessman, educator and political theorist; and his venomous personal feuds and polemics with political opponents, including future Presidents Jefferson, Madison, Adams and Monroe, culminating in an early death aged forty-nine in a duel at the hands of Vice President Aaron Burr. His life and death are sufficiently exotic to have generated a popular musical. He was one of two of the Founding Fathers never to have become President (the other being Benjamin Franklin who was considered too old for office at the time of Independence). However, as the man who established the foundations of American capitalism he is, arguably, as significant a figure as any of those who were.

The Revolutionary

Hamilton has had many biographers3 – latterly, and most comprehensively, Ron Chernow.4 But for our purposes, a few details are important to establish the context. He was born on the Caribbean island of Nevis before moving to the Danish colony of St Croix. Both islands’ economies were based on enslaved people working the sugar plantations. What are now territories renowned mainly for tourism were then important cogs in the world economy (the British tried to obtain Guadeloupe from France in return for Canada).

His family life would now be described as ‘chaotic’. He was illegitimate. His relatives would probably be dismissed today as ‘white trash’. He was fortunate, or enterprising, enough to be taken under the wing of a trader who employed him as an apprentice clerk. He also attracted the attention of a wealthy patron who encouraged his love of reading and writing (as a teenage journalist) and paid for the young Hamilton, aged seventeen, to go to North America to study, never to return.

One enduring legacy of his Caribbean upbringing was his fervent opposition to slavery. He was a strong abolitionist, which lay in part behind his subsequent quarrels with Jefferson especially, but also Madison, who held people in slavery. And his approach to economics was based in large part on his insight that economic strength came from innovation, enterprise, education and manufacturing technologies, not from exploiting enslaved people and raw materials. Long before the Civil War he identified the underlying strength of the industrial North as being its industry as against the agrarian, plantation, economy of the South (his crucial work in developing manufacturing was later acknowledged by Abraham Lincoln).

Soon after Hamilton embarked on his college education he was caught up in the colonial uprising against the British crown. He achieved early recognition as a nineteen year old, reportedly making a stirring speech at a mass meeting in support of the Boston Tea Party rebels in 1774. And when military hostilities broke out a year later, Hamilton supported the revolution, albeit initially with a journalistic pen rather than a sword. His writings, alongside his legal studies, did betray a tendency, later held against him by his political enemies, to disdain disorder and the populist politics of the uneducated common man. In the current era, he would perhaps have been marked down as an intellectual elitist and apologist for the ‘establishment’, despite his humble origins. His speeches at that time also demonstrated his preoccupation with the fact that economic relations with the colonial British authorities were heavily one-sided and needed rebalancing. In one of his pamphlets he foreshadowed the mature Hamilton: ‘we have food and clothing in plenty: as for those articles we import from abroad, why not manufacture them ourselves?’5

By the following year (1776), however, Hamilton was founding and leading an artillery troop of sixty-five men and within months had come to Washington’s attention for his courage under fire and organizational ability. In the early days of the war, when the rebels were mostly in retreat, Hamilton’s reputation grew and, aged twenty-two, he was one of Washington’s aides-de-camp and a lieutenant-colonel, rising to become, in effect, Chief of Staff. In the years of warfare which followed he would become a heroic soldier despite Washington’s instructions to stay away from the battlefield and he greatly improved the logistics of Washington’s army. But he also found the time to devour books on classical philosophy (Hobbes, Cicero, Bacon) and history and economics (particularly Adam Smith); to marry into a rich and socially respected family; and to develop a clear philosophy, shared with Washington, for post-revolution America. They envisaged a federal rather than confederal state, with a national army, a strong executive and national unity.

Politics and Policy

In the closing stages of the war against the British colonial authorities and before winning recognition for heroism at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781, Hamilton focused his attention on practical policy issues, especially regarding the economy.

The United States at that time was a small, agrarian country. There were no cities with a population of more than 50,000 in an overall population of 3 million. There was virtually no industry: only one cotton mill in 1791 (there were around 100 by 1808). The economy was badly damaged by the restrictions on exports to Britain (they fell from £1.75 million in 1774 to £750,000 in 1784). And there was double-digit inflation as a result of the demands of the war, greatly reducing the value of the dollar against gold.

In 1781, as the end of the war drew near, Hamilton produced a blueprint for dealing with fiscal crisis involving federal taxation, the creation of a national bank, the use of bond markets and foreign borrowing to raise credit for the government, and a system of public debt management. His contemporaries were also shocked by his open acknowledgement of the useful role of what he called ‘moneyed men’: the fiscal crisis ‘links the interests of the state with those of the rich individuals belonging to it’.6

A year later he published the ‘Continentalist’ essay which advocated higher tariffs – albeit moderate and effective – on a range of goods, mainly for revenue reasons. Protectionism was the norm in Britain. As a result, US exporters faced severe duties on wheat, tobacco, rice and fish. So, Hamilton was reflecting the mercantilist orthodoxy of the day which valued exports over imports and trade surpluses over deficits. Although he had read and been impressed by the arguments of Adam Smith – the ‘division of labour’ and the ‘hidden hand’ of the markets –‘free trade’ had little attraction to him. Indeed, his priority was to restore solvency and pay soldiers. Such a task needed taxes, especially import duties (collected by a strong centralized government machine).

His writing, at this stage, also betrays his contempt for populism and easy solutions, pandering to ‘what will please, not what will benefit the people’.7 Nonetheless, he opted for the grubby world of politics and became a member of the Confederation Congress (representing New York).

In the aftermath of the War of Independence, Hamilton maintained a polymath existence as lawyer, politician, journalist and campaigner (against slavery). He established a (private) bank for New York, providing the first stock ever to be traded on the New York Stock Exchange. In one of his few lapses of judgement on economic matters he dabbled in real estate speculation in upstate New York rather than Manhattan where he would have made a fortune. He also showed the first signs of the trait that was ultimately to destroy him: an inability to resist being dragged into public arguments of invective and innuendo with political opponents. On this occasion, his opponent was the powerful Governor of New York, George Clinton. Inevitably some of the mud stuck (which included the then controversial suggestion that he was mixed race or, alternatively, the illegitimate son of George Washington).

His major contribution to posterity in these years followed from his participation as one of the fifty-five delegates from twelve states to the Convention which produced the American Constitution. Revered today as having almost religious significance, the Constitution was hammered out over months of often acrimonious argument amid much skulduggery, somewhat removed from Benjamin Franklin’s later description of it as ‘the most august and respectable assembly he was ever to see in his life’.8

The dominant intellectual influence on the Constitution was a series of essays – the Federalist papers – authored by Hamilton and Madison, which appeared in 1787. Though they would later quarrel bitterly, at that stage they were close collaborators and shared a similar view of the necessary balance to be struck between the federal government and the states. Similarly, they broadly agreed on how to achieve the necessary checks and balances between the executive, legislature and judiciary and between order and liberty. Their essays, which Hamilton often had to write in a hurry between his legal cases, are now regarded as seminal works.

Hamilton’s distinctive contribution to the papers reflects his antipathy to over-powerful state politicians and to demagogues who claim to speak for the popular will. More positively, he sketched out the commercial benefits of economic union and common monetary policy. And he managed to insert his economic philosophy, which could have come out of the mouth, or pen, of Adam Smith, that monopolistic vested interests are bound to pursue their own interests and so need to be regulated.9 Hamilton’s contribution was not merely to pump out the words; he was able, with Madison, to win – from a minority position initially – the federalist case, and then get the new Constitution approved by the states, most crucially in the recalcitrant state of New York.

The Treasury Secretary

Once the Constitution was agreed, the way was open to choose the first President: at that time, by an electoral college of state representatives, not by party or popular vote. Hamilton was determined that Washington should become President: the only man, he believed, with the stature for the job. Washington, once persuaded to run, was the clear favourite but Hamilton managed, with his characteristic lack of tact, to make a mortal enemy of John Adams, the only other plausible candidate, who became the new Vice President and, in due course, the second President of the USA. Hamilton’s reward was to become Washington’s first Treasury Secretary in 1789. At that time, it was the most powerful executive position in the new administration (one of only three, the others being Secretary of State – Jefferson – and Secretary of State for War). It was also a highly sensitive post since the new state needed to raise taxes, and taxation was potentially the flash-point for differences between federalists and the states. Yet he was clearly the best-prepared candidate for the job, having spent years reading and drawing up a detailed blueprint for government.

Within hours of being appointed he had raised a large loan for the federal government (from the Bank of New York which he himself had established) and then another from a new Philadelphia bank. Historians are agreed that he was an administrative genius who combined theory and practice, rapid decision making and careful systems building. To all intents and purposes, he became Washington’s Prime Minister, though parallels with government today are somewhat misleading (he had thirty-nine employees, the State Department five and the Department of War only two). He and the other brilliant minds of his generation were deployed creating a new state for just over 3 million people (excluding 700,000 enslaved people) with an administrative apparatus which today would be expected in the lowest tiers of local government. The juxtaposition of greatness and pettiness, visionary constitutional design and small-minded personal jealousies can only be understood in that unusual context.

Hamilton’s solution to the problem of how to finance the new state was in the form of a fifty-page report. It was typically clear-minded and radical. American governments would need to borrow at affordable interest rates for the foreseeable future; so, debt markets must be efficient and the federal government must always be trusted to honour its debts. He made explicit something we now take for granted: that the national debt will never be repaid. The task of fiscal policy is to be able to service the national debt and to maintain confidence that government can continue to borrow in the markets on good terms. If greater confidence in government securities were then to drive up their price, rewarding speculators, then so be it. By the same token, higher bond prices meant lower interest rates benefiting the economy. Furthermore, confidence in government securities would enhance their status as collateral for private business borrowing and thus for expansion of the money supply, which he saw as essential to maintaining economic activity (his writings on the quantity and velocity of money in circulation show a remarkably modern approach to monetary policy). To uphold confidence that the government would always honour its obligations to creditors, expandin...