eBook - ePub

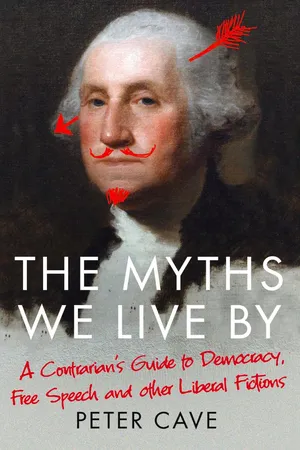

The Myths We Live By

A Contrarian's Guide to Democracy, Free Speech and Other Liberal Fictions

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Myths We Live By

A Contrarian's Guide to Democracy, Free Speech and Other Liberal Fictions

About this book

In this witty and mischievous book, philosopher Peter Cave dissects the most controversial disputes today and uses philosophical argument to reveal that many issues are less straightforward than we'd like to believe. Leaving no sacred cow standing, Cave uses ingenious stories and examples to challenge our most strongly held assumptions. Is democracy inherently a good thing? What is the basis of so-called human rights? Is discrimination always bad? Are we morally obliged to accept refugees?

In an age of identity politics and so-called 'fake news', this book is an essential resource for reinvigorating genuine public debate - and an entertaining challenge to accepted wisdom.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Myths We Live By by Peter Cave in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Ethics & Moral Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

What’s so good about democracy?

It seemed a great idea at the time. Being a democrat and liberal, I joined the Good Ship Democracy for a Mediterranean cruise. It possessed vast attractions for me, not least because my fellow passengers would, no doubt, be of my persuasion: all for democracy, for equal rights, for free speech.

Trouble started when the crew noticed that there were storms to the East and rocks to the West. ‘Which way should we steer – or should we turn back?’ they asked.

Foolish as I am, I assumed that the ship would deploy the services of a captain or pilot with expertise and knowledge of the Mediterranean seas, storms and safe harbours. The crew explained the error of my thinking. On the Good Ship Democracy, it transpired, we needed to vote on such matters, on all such matters.

‘But I have no idea which is the best way to go, which is the best way to vote,’ I complained, feeling a little irritated – and, yes, very worried. Other passengers joined in, agreeing that voting in this context was a silly and dangerous procedure. Others, though – the travelling know-it-alls – had no doubts, waving away our complaints. ‘We know what it is best to do,’ they insisted. It was a pity that those with such certainty disagreed with each other over what exactly that was. What exactly was the best thing to do?

The crew told us not to fret. Before we voted, we would be provided with charts, weather forecasts and instruction guides on how to assess those charts and forecasts. That struck us as making some sense: we could then evaluate the conditions and vote accordingly. That did indeed strike us as making good sense, until we realized that different sailors were providing us with conflicting data and very different readings of the data; in fact, much of the data seemed as baffling to the sailors as to us. Further, it soon became clear that some of us were pretty gullible or careless in reasoning; and some sailors were far more silver-tongued than others. The old hands wined and dined us, eager to persuade us of their expertise; others, it transpired, had personal reasons for what they advocated: some were wanting to turn back because missing the comforts of lovers left at home; others wanted to press on regardless, in expectation of adventurous romances to come.

The voyage continued in this way – or, rather zigzagging ways – as more decisions were required, more votes taken, with little consistency of approach manifested by our votes. How we envied other cruises that seemed to know exactly how to go and where to go.

Our Good Ship Democracy would still be meandering across the seas, save for the rocks that it struck. We abandoned ship, with some emergency helicopters coming to our rescue, manned by the military. Fortunately, we were not asked which way to fly to reach the shore.

The vignette above has at heart a fundamental criticism of democracy, as expressed by Socrates in Plato’s dialogue, Republic. The dialogue was written around 380 BC in ancient Athens, being the first substantial and enduringly influential text of political philosophy. Surely, we need experts – philosophers, indeed – to assess the best way for a society to run; Plato referred to those individuals as ‘Guardians’ of the ideal society, of the Republic. Even with the charts provided when on board Good Ship Democracy, few of us could have made sensible judgements. Even if the electorate is well-informed, there are many doubts about how competent most members are in assessing economic likelihoods, social justice and international relations – even in assessing their own best interests. In any case, if there is a right answer, why go through the ritual of voting and why take the risk of assuming that the majority vote reaches that answer?

‘Ah,’ it is replied to Plato, ‘no doubt we need experts for the means, explaining the different means to an end; but, in contrast to deliberating about means, we surely should all have a say in what sort of society we want, what we are aiming to achieve and what we are prepared to countenance to secure those aims. There is no “the” right answer for there is a plurality of ways of living.’

It is true that most of us cannot work out economic and social implications of a variety of different policies; experts, though, can often tell us what is likely to happen as a result of certain policies, the risks involved and how society would develop for the different groups within. We can then vote on the basis of which policies overall we prefer: that is where the democratic vote of the majority justifiably comes to the fore.

Plato would disagree. Plato’s approach would have not merely an expert captain, steering us clear of rocks and storms, but a captain who would also be expert in telling us what our destination should be, which destination is best for us – best, indeed, for one and all of us.

Surely, many continue to insist, Plato is wrong in his belief in the existence of an expertise in ends. It is up to us whether we should prefer to end up in Turkey, Israel or Egypt – and it is up to us what kind of society we want. Some people may prefer a society destined towards low taxation and few social-welfare benefits; others may prefer just the opposite. Some may prefer a society that promotes free thinking, alternative ways of living and religion; others may prefer conformity and tradition. Once experts have informed us of the different viable means to the various desired ends, then it should be for us to decide which to follow.

Our reply to Plato, as implied, is grounded in a ‘pluralism’; there are different ways of living, different ends, different priorities regarding the means. No expert can tell us which are the best. We have some diverse values, conflicting desires and a spectrum of attitudes to risk. As already indicated, some people prefer society to be liberal, where citizens’ conduct is relatively unconstrained; some prefer a more regimented society where we all ‘know our place’. Some may be easy-going over the availability of abortion, voluntary euthanasia and same-sex marriages; others, perhaps for religious reasons, would impose restrictive laws pertaining to such matters. Priorities also differ: some place health services provided by the State as of higher value than speedier rail connections. In Britain there is considerable scepticism by many about the billions of pounds to be spent on the HS2 rail project – a vanity project, as it is seen – billions that could be better spent on social care and housing.

The above observations can have light cast upon them by the philosophy of David Hume, the great Enlightenment Scot of the eighteenth century. Hume was a good-humoured man who would obliterate his philosophical melancholy and scepticism by dining, conversing with friends and playing backgammon. In his A Treatise of Human Nature (1738) he makes the point that preferences, passions – what we ultimately value – are not determined by reason:

’Tis not contrary to reason to prefer the destruction of the whole world to the scratching of my finger. ’Tis not contrary to reason for me to chuse my total ruin, to prevent the least uneasiness of an Indian or person wholly unknown to me. ’Tis as little contrary to reason to prefer even my own acknowledge’d lesser good to my greater, and have a more ardent affection for the former than the latter…

Being human, we naturally have plenty of preferences in common – few choose their total ruin – but we do not all possess the same preferences regarding how society should run. No expertly reasoned answer is available about which ways of living are politically best justified; hence, a mechanism is needed to determine what politically should be done. That mechanism is the democratic vote.

Some individuals would no doubt prefer to follow their own agreed way of living; they can readily grasp how others also have preferences to have their own, but different, ways. Attempted resolution by physical battle would lead to chaos for all; leaving the field, becoming hermits, has few attractions. Democracy, by contrast, has a central attraction; it offers an approach where, it seems, we can all have a say in what to say, in how we are ruled. We all can vote; we can all agree to accept the outcome. It is as simple as that – except it is not simple and not as simple as that.

Most people today approve of democracies. Dictatorships seek the linguistic privilege of deeming themselves ‘democracies’ sometimes even in their formal names. We have, for example, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria. Such dictatorial democracies receive much mockery from the ‘true democracies’ of the West. To cast serious doubt on democracy in practice there is, in fact, no need to fly off to those dictatorships enmeshed in linguistic gymnastics. We could simply look at our own Western democracies, as we shall do in Chapter 2. In this chapter the attention is directed at the defects of democracy even as an ideal to be pursued – though, to expose certain defects, we shall inevitably encounter some clashes with the practice.

It is important to note: the reasoning above regarding how democracy is needed to handle conflicting preferences was not itself justified by democratic votes. Democratic voting may justify the policies governments pursue, but it cannot justify using democratic voting – for that would be circular, akin to lifting yourself, as is famously said, by your bootstraps. Democratic voting was justified above (be it well or poorly) by reasoning regarding what individuals should rationally accept as the best way to run a society. Plato would approve of the approach – that of rationality – but, as seen earlier, argues that there are faults in the reasoning in favour of democracy.

DEMOCRACY: FAILURE IN THEORY

A democracy, in essence, consists of some machinery: there is an input from ‘the people’, various wheels turn, levers clang, steam hisses – and the eventual outcome is a government. What the government does is meant to bear some relationship to the interests of the people whose votes were the inputs. What is the relationship? Surprisingly, there is vagueness at a most fundamental level.

When people vote – even the most reflective – they are unclear how they should be determining their votes. What does democracy theoretically require? Listen to voters. Some openly say that they are voting in what they consider to be their best interests – or their grandchildren’s best interests – or what is best for the planet. Others may be doing their best to vote on what is best for the society or best for people in general or for the poor – or to be in accord with certain religious beliefs. There is a mishmash of aims.

True, the machinery could be justified as a means of delivering a result when people’s interests and aims differ; and people should simply vote in their own (perceived) best interests. The machinery, though, could be justified as delivering a proper result only if voters vote on what they sincerely think is in the community’s best interests. In neither case, though, is the outcome satisfactory.

If people are voting in what they take to be their own interests, there is no reason at all to believe that the machinery (however it works) delivers something that is in fact in the interests of the community or even in the interests of the majority of voters. If people are voting in what they take to be the community’s interests, there is no reason to believe that the machinery delivers what is in fact in the community’s interests. People make mistakes both about what is in their own interests and about what is in the community’s. Unless we ascend to Platonic heavens, we are stuck here in the grubby real world of mistaken views, genuine bafflement and conflicting interests. After all, the interests of corporate executives do not typically coincide with the interests of those working on factory lines. True, all may, for example, have the same interest in reducing the number of murders, but democratic voting is no reliable means to achieve that desirable reduction. In Britain a majority often call for the reintroduction of capital punishment – but that majority view could be in the belief that capital punishment deters would-be murderers, a belief for which there is no convincing evidence.

Even if we accept that people should vote on policies on an ordered-preference basis – first choice is this; second choice is that; weigh accordingly – determined by their own interests, contradictions can arise, leaving it unclear how to determine the ‘right’ collective decision. An example is in this chapter’s endnotes. As the economist and Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen quipped, ‘While purity is an uncomplicated virtue for olive oil, sea air, and heroines of folk tales, it is not so for systems of collective choice.’

It is time to wheel on stage Jean-Jacques Rousseau, an eighteenth-century philosopher, born in Geneva, a major influence on the Enlightenment and indeed the French Revolution through his ideas in The Social Contract (1762). Here we meet his notion of the ‘General Will’ – the Will that advances the community’s interests and upholds the interests of all the citizens. Mysteriously, the General Will is constant, unalterable and pure; mysteriously, it can be discovered if people vote for what they believe is in the community’s interests. Now, it is certainly plausible that in a village, club or small enterprise, members may have a strong sense of community and will vote for what they honestly believe is best for the community – and get it right. That sense of community, though, may not be very strong when we have in view a vast nation, itself made up of very diverse groupings. Despite that, Rousseau proclaims the benefits of outcomes determined by majority votes. Here is how.

In a reasonably sized community – in fact, the larger the better – majority opinion, argues Rousseau, is more likely to be right on any matter than any individual voter. This may be laughed out of court, but it has a mathematical justification given by Nicolas de Condorcet, a liberal thinker of the eighteenth century, a thinker much exercised with problems of majority voting and collective decisions; he criticized the French revolutionary authorities and ending up dying in prison. His Jury Theorem shows the advantages of following majority votes, albeit on assumptions that are highly unlikely to hold in typical national elections. The assumptions are that all voters are cooperating to find a mutually beneficial answer to the same question and each has an equal and better-than-evens chance of getting it right – or even, in some versions of the theorem, that the average is better than evens. Then, over the long run – an important qualification – the majority is more likely to be right than any individual. Of course, we have no reason to think that each voter has a better-than-evens chance of getting things right, even if they are independently and sincerely voting for what they believe is in the national interest. Further, if they do not have the better-than-evens chance, then the mathematics shows that the majority outcome is more likely to be wrong.

An obvious practical case of a majority of those who voted getting matters wrong is the outcome of the 1933 election in Germany. Under the Weimar Republic, most people were having a bad time, but after voting in Adolph Hitler, leader of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (the Nazi Party), matters became substantially and radically worse – obviously for the Jews in Germany, but also for Germans more generally and, indeed, for millions of people outside of Germany.

There remains, of course, the fundamental challenge, namely whether there is anything that is the ‘getting it right’, the best for the community, for society. Perhaps it is elusive. If only we could reason better or heed the ways of Plato’s Guardians or even make sense of Rousseau’s mysterious General Will, our eyes would be opened to the glittering prize of ‘the best’. There is, though, no good reason to believe it exists. After all, why think there is only one way of ruling, of voting – of living – that is rightly understood as in the interests of the community? In addition, even if certain minimal requirements could be shown to ground what is best for the community as a whole, it does not follow that they provide what is best for each and every mem...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Prologue: On hiding what we know

- 1 What’s so good about democracy?

- 2 How democracy lies

- 3 Freedom and discrimination: burqas, bikinis and Anonymous

- 4 Should we want what we want?

- 5 Lives and luck: can Miss Fortuna be tamed?

- 6 The Land of Justice

- 7 Plucking the goose: what’s so bad about taxation?

- 8 ‘This land is our land’

- 9 Community identity: nationalism and cosmopolitanism

- 10 What’s so good about equal representation?

- 11 Human duties – oops – human rights

- 12 Free speech: the Tower of Babel; the Serpent of Silence

- 13 Regrets, apologies and past abuses

- 14 ‘Because I’m a woman’: trans identities

- 15 Happy Land

- Epilogue: In denial

- Notes and References

- Acknowledgements

- Index