eBook - ePub

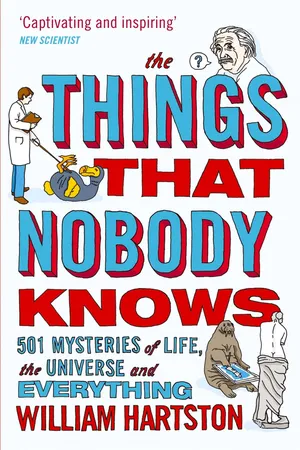

The Things that Nobody Knows

501 Mysteries of Life, the Universe and Everything

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

HERE ARE MANY, MANY THINGS THAT NOBODY KNOWS... Why are so many giraffes gay?

Has human evolution stopped?

Where did our alphabet come from?

Can robots become self-aware?

Can lobsters recognize other lobsters by sight?

What goes on inside a black hole?

Are cell phones bad for us?

Why can't we remember anything from our earliest years? Full of the mysteries of life, the universe and everything, The Things that Nobody Knows is a fascinating and unputdownable exploration of the limits of human knowledge of our planet, its history and culture, and the universe beyond.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Things that Nobody Knows by William Hartston in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Science General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CONTENTS

Introduction:

Aardvarks

America

Ancient History

Antarctica

Anthropology

Armadillos

Australia

Bats

Bees

Biology

Birds

Black Holes

Boudicca

The Brain

Brussels

Butterflies

Cannibalism

Cartography

Cats

Chemical Elements

Chimpanzees

Christianity

Cleopatra

Climate

Coffee

Composers

Consciousness

Cosmology

Dinosaurs

Disease

DNA

Dodos

Dogs

Druids

The Earth

Earthquakes

Easter Island

Economics

Egyptology

Einstein

English History

English Language

Evolution

Football (American)

French History

Fundamental Particles

Games

Garlic

Genetics

Giraffes

The Greeks

Hair

Handedness

Human Behaviour

Human Evolution

Insects

Inventions

Jesus Christ

Judaism

Language

Magnetism

Mammals

Marine Life

Mathematics

Medicine

Memory

The Middle Ages

Modern History

The Moon

Mozart

Murder

Music

Musical Instruments

Numbers

The Old Testament

Olm

Painting

Palaeontology

Pandas

Penguins

Philosophy

Physics

The Planets

Plankton

Plants

Popes

Prayer

Prime Numbers

Proteins

The Pyramids

Quantum Physics

Reality

Rome

Sex

Shakespeare

Sleep

Smoking

The Solar System

The Sphinx

Spiders

Spontaneous Combustion

Squirrels

The Sun

Tardigrades

Unicorns

The Universe

Venus de Milo

Water

Weather

Worms

Writers

Writing Systems

Yeti

Zymology

and finally

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Index

INTRODUCTION

Ignorance, Fruit-Fly Genitalia and the End of the World

There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we now know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns. These are things we do not know we don’t know.

Donald Rumsfeld, 12 February 2002

The trouble with people like Donald Rumsfeld is that they give ignorance a bad name. The US Secretary of State for Defense was generally derided when he made the clumsy statement quoted above, but he was just trying to remember a line from Confucius quoted by Henry David Thoreau in Walden (1854):

To know that we know what we know, and that we do not know what we do not know, that is true knowledge.

With the wisdom of Confucius supporting him, Thoreau went on to ask:

How can we remember our ignorance, which our growth requires, when we are using our knowledge all the time?

While Rumsfeld was simply categorizing different levels of not knowing, Confucius and Thoreau had a much more positive approach to ignorance, an approach that provides the basic raison d’être of this book. I come to praise ignorance, not to bury it; for there is no better key to understanding the vast and ever-growing expanse of human knowledge. The topics covered in the forthcoming pages are exactly what the book says on the cover: things that nobody knows. Many people, when I have mentioned the title of the book, have unjustifiably assumed it to be another of those not-many-people-know-that collections of useless information. It isn’t. There may be a great number of such intriguing facts here, but they are only included when they are crucial to explain what nobody at all knows, and why nobody knows it.

More than three hundred years ago, the French philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal likened our knowledge to a sphere which, as it grows larger, inevitably increases the area with which it comes into contact with the unknown. Henry Miller put this more succinctly in The Wisdom of the Heart (1941):

In expanding the field of knowledge we but increase the horizon of ignorance.

This book is a guided tour around Miller’s horizon of ignorance.

When listening to scientists or other experts talking about the latest advances in their fields, I have always found it more intriguing, and generally more enlightening, when they get on to the subject of the things they don’t know. Rumsfeld’s known unknowns are what determines the direction of future research – and that is what makes ignorance so exciting.

According to a recent estimate in the on-line Ulrichsweb periodicals directory, there are around 300,000 academic journals currently being published around the world. These may come out weekly, monthly or less frequently, but the total number of issues of all these journals in any year must be over 3 million, and with an average in the region of ten papers in each journal, each reporting a previously unknown result, that adds up to over 30 million additions to our knowledge every year, which is more than six every second. There has to be a vast amount of ignorance out there to keep all those journals in material, and the things that nobody knows that I have identified in the pages that follow only scratch the surface.

I ought now to write something about ontology, epistemology, Karl Popper’s concept of falsifiability, Thomas Kuhn’s paradigm shifts and everything else that contributes to our ideas of reality, knowledge and what is knowable, but there will be plenty of time for that sort of thing later when we get on to the subject of philosophical unknowns. There is, however, just one more subject that I want to mention: fruit-fly penises.

Male fruit flies have tiny hooks and spines on their penises, the function of which – until recently – nobody knew. The standard way to resolve such a question would be to shave these bristles off and see what effect this had on the sex life of the subject. In the case of fruit-fly penises, however, the bristles are so small they can only be seen under a microscope, and even the best scalpel is too clumsy an instrument to attempt to use as a razor. At the end of 2009, however, researchers at the University of California published a paper describing a method of shaving fruit-fly penises with a laser. Not only could they shave off the bristles, but they could even perform the task with such accuracy that only the top third of each bristle was trimmed. By comparing the sexual exploits of unshaven, partially shaven, and totally shaven fruit flies, they could then tell everyone what they wanted to know. Answer: the sole role of the hooks and spines is to act as biological Velcro and keep the male fruit fly attached to the female during sex.

And until the paper was published, that is probably something that even Donald Rumsfeld did not know that he did not know.

After toying with various ways of organizing the material, I finally decided to settle for the most systematically arbitrary of all: alphabetical order by subject. Where appropriate, I have included cross-references to related topics at the end of the subject sections. These are introduced by the words ‘see also’, followed by the name(s) of the related subject or subjects and the numbers of the relevant unknowns. There are also cross-references embedded within the body of the entries, directing the reader to other entries that shed further light on the topic under scrutiny.

Before diving into the deep end of our pool of ignorance, I cannot resist concluding this introduction with an example of a question we know we can’t answer – at the time of writing, anyway. The question is

Will the world end in 2012?

More precisely, the question is whether the world will end on 21 December 2012, a date supposedly predicted by the ancient Mayans. The calculation is based on the Mayan Long Count Calendar, which must be the most complex way of counting our days that humanity has ever devised. Rather than expressing a date in three figures, as the day, month and year (originally chosen to correspond to the period of rotation of the Earth, and the orbits of the Moon around the Earth and the Earth about the Sun), the Mayans used five figures from interwoven counting systems. There were 20 days (called K’in) in a Winal, 18 Winal in a Tun, 20 Tun in a K’atun, 20 K’atun in a B’ak’tun. A Long Count ended after 13 B’ak’tun. Multiply all these together, and you get 1,872,000 days in a Long Count, after which it starts again. That’s just over 5,128 solar years, and since the Mayan calendar began on 11 August 3114 BC, the calculations mean that it will reach its end on 21 December 2012 (remember there was no year zero in our calendar).

Actually the Mayans did not predict the End of the World on that date, nor even a great cataclysm, and some say the date had no more significance than any 1st of January, but it’s a good excuse for a blockbuster movie, and NASA has been plagued with phone calls from people who believe in it, some even saying that they are contemplating suicide to avoid the horrors that the End of the World may bring.

So the good news is that the world will probably not end in 2012, but we shall definitely know whether the prediction is correct on 22 December of that year.

To be conscious that you are ignorant is a great step to knowledge.

Benjamin Disraeli, Sybil (1845)

AARDVARKS

1. Is the aardvark the closest living relative of a creature from which all mammals evolved?

In 1999 scientists sequenced and analysed the complete mitochondrial DNA of the aardvark, an unprepossessing, somewhat comical ant-eating creature from Africa, whose name is Afrikaans for ‘earth pig’. The results showed that the aardvark may be the closest living relative of the ancient ancestor of all the placental mammals – that is, all mammals, including ourselves, apart from marsupials and the egg-laying monotremes (such as the duck-billed platypus). Surprisingly, the genetic make-up of the aardvark is closer to that of the elephant than the South American anteater, which shares its taste in food and its general appearance.

Research suggests that the chromosomes of the aardvark have undergone relatively little change since placental mammals first evolved over 100 million years ago, but how close the first placental mammal was to the aardvark of today is unknown.

Our knowledge can only be finite, while our ignorance must necessarily be infinite.

Sir Karl P...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Author biography

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Epigraph page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Aardvarks

- Climate

- Human Evolution

- Popes

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography

- Index