- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

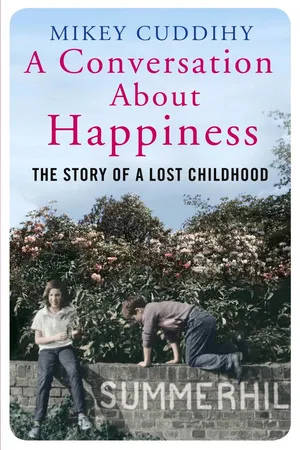

When Mikey Cuddihy was orphaned at the age of nine, her life exploded. She and her siblings were sent from New York to board at experimental Summerhill School, in Suffolk, and abandoned there. The setting was idyllic, lessons were optional, pupils made the rules. Joan Baez visited and taught Mikey guitar. The late sixties were in full swing, but with total freedom came danger. Mikey navigated this strange world of permissiveness and neglect, forging an identity almost in defiance of it. A Conversation About Happiness is a vivid and intense memoir of coming of age amidst the unravelling social experiment of sixties and seventies Britain.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Conversation About Happiness by Mikey Cuddihy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Contents

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Part Two

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Acknowledgements

A Note on the Author

Part One

Chapter 1

Uncle Tom picks us up from summer camp in the Catskills, all five of us. That’s me, my big sister Deedee, my brothers Bob, Sean and Chrissy. Instead of going home, we drive to the airport where we get on a plane to London for a sightseeing holiday.

I’m quite excited at the prospect of seeing the Queen.

‘I don’t want to go to England. I want to stay home and play Little League baseball,’ screams Sean as Uncle Tom drags him up the steps and hauls him into the plane.

Twenty months older than me, Sean senses that more than a holiday is afoot.

It’s late summer 1962. I’m ten years old. Kennedy is in his second year as President and Marilyn Monroe has been found dead in her bedroom from an overdose. I arrive at Heathrow in just the clothes I’m standing in: a pair of shorts and a candy-striped cotton shirt with chocolate ice-cream stains down the front. I’m clutching a white calico dachshund under my arm with the autographs of all the friends I’ve made during our six weeks at Camp Waneta. I rub my legs to combat the chill and walk uncertainly down the metal steps, squinting out at a drizzly grey sky.

They say Mom never regained consciousness. November 1961 and it’s raining. My mother turns a corner too sharply and the family Packard skids on fallen leaves. The car hits the tree. Mom goes straight through the windscreen, the steering wheel crushing her chest.

There are rumours amongst my older siblings that Mom had been on the verge of leaving my stepfather. Perhaps her death hadn’t been an accident. Another rumour has it that she’d started drinking again so was driving erratically or maybe, they speculated, she was so dosed up on tranquillizers that her reflexes were bad. My big brother Bob blames my stepfather or ‘the Gooper’, as he calls him behind his back, for being too mean to have the car fixed. One of the doors was tied shut with an old piece of washing line and he knew that the brakes were dodgy.

We all blame ourselves to some extent.

Our father died four years earlier in his own car accident, driving a much racier Ford Coupé.

Five years old, I put on a new dress my stepmother has made me. I go into the living room to show him my dress. Daddy has come home from work and is sitting in his comfortable Ezy-Rest armchair, ice cubes clinking in his whisky glass.

I do a twirl for him.

‘Very nice.’ Daddy gives an approving smile, pats me on the head, and I toddle off happily to get ready for bed.

I’m puzzled when I wake in the morning to be told that Daddy is dead. He died on his way home from the city. But I had seen him with my own eyes just last night.

So now we’re orphans.

This is where Uncle Tom steps in, setting the wheels in motion to adopt us. My father comes from a huge, Irish-Catholic family who have done extremely well in publishing on one side (Funk and Wagnalls, The Literary Digest), and inventing on the other (his grandfather was the millionaire inventor, T. E. Murray). He’s one of five brothers and two sisters who adored him; he was a tearaway, the black sheep, or Robert the Roué, as they affectionately called him, later shortened to ‘Roo’.

Uncle Tom has the same good looks as our father; his dark hair made even darker with Brylcreem, the same wry, gentle smile, a fatherly way of patting me on the head. With his soft authoritative voice, the Manhattan accent with the flattened vowels, he even sounds like Daddy. It’s difficult to tell them apart in photos, so he’s a fitting stand in as far as we’re concerned. Tom jokes that he’s ‘drawn the short straw’ when he takes us on, and I imagine my uncles sitting in my grandmother’s Park Avenue apartment drawing straws from someone’s hands – perhaps Arthur, the butler, proffering the straws like fancy hors d’oeuvres.

Uncle Tom studied economics at Harvard and went into investment banking, but after three children and a messy divorce at the age of thirty he dropped out, returning to university to take a PhD in psychology.

My sister says he kidnapped us.

Deedee is called into the principal’s office at her high school one lunchtime: ‘Edith, your uncle is here to see you.’

Deedee hasn’t seen Uncle Tom for a long time. He takes her out for lunch, to Herb McCarthy’s, a sophisticated bar and grill in town. She orders her favourite thing, a grilled cheese sandwich and a Coca-Cola.

‘How would you like to come and live with me here in Southampton? I’ve rented a place on Herrick Road just around the corner from your school.’

My sister is thinking: Uncle Tom looks rich. His plan sounds like a load of fun. Maybe I’ll get my very own Princess telephone.

‘Yes, OK,’ she says. ‘But what about the others, and Larry, and Mimmy?’

‘I’ve squared it with them, don’t you worry!’ (Of course he hasn’t.)

‘I’ll send a car to pick you up after school, and your sister and little brothers. You can move in straightaway.’

My brother, Bob, holds out for a while, loyal to Mimmy, my mother’s mother, and even to my stepfather, Larry, whom he had reviled when my mother was alive. But he knows it’s hopeless, and anyway, sharing a house with Uncle Tom seems like a better proposition than living with our exhausted stepfather and our frail and crotchety grandma.

Our new house is a lovely shingle affair with a porch. It’s located on one of the prettier streets behind the Presbyterian Church in town, not far from school. Uncle Tom indulges our every whim. Mine is that I want to be called Elizabeth, my middle name, instead of Mikey, named for my father’s favourite brother, Michael, who was struck down with polio at the age of nineteen. This is occasionally lengthened to Michael when my sister is angry with me.

Tom installs a kind black couple, George and Lessie-May, to look after us during the week – he’s working in the city weekdays – and so now we’re all set. But one of us is missing – my half-sister, Nanette, and although I have my own very nice room in a clean and ordered house, my little sister isn’t here. She’s only four and a half years old and she belongs to my stepfather, so he keeps her.

At weekends, Uncle Tom makes us do inkblot tests, ten little cards invented by someone called Rorschach. They remind me of the flash cards in kindergarten, with a picture of an apple, or a dog, where you have to say what it is. This time, there are shapes – blobby and symmetrical.

‘Tell me what you see,’ says Tom.

Is this a trick question?

‘Rabbits, twin baby elephants, an angel, butterflies. Gosh, maybe a couple of Russian Cossacks… dancing wearing red hats.’

‘Good,’ says Tom.

He seems pleased with my answers. He appears pensive, sometimes a little surprised-looking, but there never seems to be a wrong answer. I like the Rorschach test better than the kindergarten flash cards. They’re more interesting.

The first thing Tom does to make his claim for custody more viable is quickly to marry a girlfriend of his, Joan Harvey. Joan is beautiful and funny and an actress. She stars in the popular TV soap, The Edge of Night. She devises ways of saying hello to us when she’s on TV.

One morning when she’s leaving for the city, she says, ‘Watch for me touching my right ear, that’ll mean I’m saying hi.’

We rush home from school, take our peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and glasses of milk to the living room, and scrutinize the television. Sure enough, at the given moment she gives the signal. We whoop with delight.

Uncle Tom has had a wealthy and privileged upbringing, but it’s also been conservative and religious. The boys were sent away to Benedictine boarding schools, my father to a Catholic military academy run by Jesuits, and the girls to the Convent of the Sacred Heart. My brother Bob, aged fifteen, is at the same military establishment and my sister spent a term at Kenwood, a Catholic boarding school in Albany, New York, before returning to our local high school. We three younger kids have so far escaped these types of schools, my mother opting instead for the local elementary. God only knows what my wealthy grandmother had in store for us.

My Uncle Tom wants us to have something better, in England, where we’ll be able to make a fresh start, leave the past behind and begin again.

The thing is, he isn’t coming with us.

When Uncle Tom shows up at Camp Waneta, I haven’t seen him for over a month. He takes us out to a diner in town. Acker Bilk’s ‘Stranger on the Shore’ is playing on the jukebox. The tune is the background melody to the summer; it seems to be playing wherever we go. I make up words, singing along to the plaintive clarinet solo in my head:

I don’t know why, I love you like I do;

I don’t know why I do; I do, I do I do.

The birds that sing their song,

Are singing just for you.

I don’t know why I love; I do, I do, I do.

Uncle Tom has a camera with him and wants to take photos of us. He gets us to pose, individually, not together like a happy family.

‘Deedee, can you stand over there, against the sky. I need you on a pale background. Good. Mikey, you next.’

I smile as best I can.

‘Well, kids, I guess that just about wraps it up for the time being. See you in a couple a weeks.’ And off he goes.

Sure enough, two weeks later, Uncle Tom comes to get us in a big station wagon. My Aunt Joan is with him. There’s lots of luggage in the back. There are five duffel bags, each with our names written in heavy marker pen on the straps. I’ve been looking forward to seeing my little sister Nanny, my Grandma Mimmy and my toys, but we don’t drive home like I expect. We drive straight to Idlewild airport and on to the plane.

As usual Uncle Tom is accompanied by an entourage of strange men. Seven of them have come to see him off. Saul, a grey-haired man who seems to be in charge, is giving Uncle Tom an injection. Standing on the runway, my uncle has his sleeve rolled up. He’s afraid of flying. So am I, but I’m afraid of injections too, so I keep quiet.

My uncle’s friends take turns to hug him and pat him on the back.

‘You can do it, Tommy, have courage,’ they say, which is puzzling, because we’re only going to England for a week.

Joan doesn’t come with us.

When I ask her what she will be doing, and won’t she be lonely without us, she says, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll stay home and play with myself.’

My older brothers and my sister laugh, as if she’s told a very funny joke. Then my Uncle Tom hands out our passports with the photos taken at Camp Waneta, against the pale blue sky.

In London, we stay in a little hotel off L...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Part One

- Part Two

- Acknowledgements

- A Note on the Author