![]()

PART I

You can keep as quiet as you like, but one of these days somebody is going to find you.

Haruki Murakami, 1Q84

![]()

one

JUBILEE

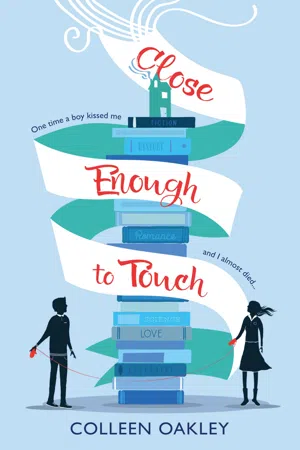

ONE TIME, A boy kissed me and I almost died.

I realize that can easily be dismissed as a melodramatic teenagerism, said in a high-pitched voice bookended by squeals. But I’m not a teenager. And I mean it in the most literal sense. The basic sequence of events went like this:

A boy kissed me.

My lips started tingling.

My tongue swelled to fill my mouth.

My throat closed; I couldn’t breathe.

Everything went black.

It’s humiliating enough to pass out just after experiencing your first kiss, but even more so when you find out that the boy kissed you on a dare. A bet. That your lips are so inherently unkissable, it took $50 to persuade him to put his mouth on yours.

And here’s the kicker: I knew it could kill me. At least, in theory.

When I was six, I was diagnosed with type IV contact dermatitis to foreign human skin cells. That’s medical terminology for: I’m allergic to other people. Yes, people. And yes, it’s rare, as in: I’m only one of a handful of people in the history of the world who has had it. Basically, I explode in welts and hives when someone else’s skin touches mine. The doctor who finally diagnosed me also theorized that my severe reactions—the anaphylactic episodes I’d experienced—were either from my body over-reacting to prolonged skin contact, or oral contact, like drinking after someone and getting their saliva in my mouth. No more sharing food, drinks. No hugs. No touching. No kissing. You could die, he said. But I was a sweaty-palmed, weak-kneed seventeen-year-old girl inches away from the lips of Donovan Kingsley, and consequences weren’t the first thing on my mind—even if the consequences were deadly. In the moment—the actual breathless seconds of his lips on mine—I daresay it almost seemed worth it.

Until I found out about the bet.

When I got home from the hospital, I went directly to my room. And I didn’t come out, even though there were still two weeks left in my senior year. My diploma was mailed to me later that summer.

Three months later, my mom got married to Lenny, a gas-station-chain owner from Long Island. She packed exactly one suitcase and left.

That was nine years ago. And I haven’t left my house since.

I DIDN’T WAKE up one morning and think: “I’m going to become a recluse.” I don’t even like the word “recluse.” It reminds me of that deadly spider just lying in wait to sink its venom into the next creature that crosses its path.

It’s just that after my first-kiss near-death experience, I—understandably, I think—didn’t want to leave my house, for fear of running into anyone from school. So I didn’t. I spent that summer in my room, listening to Coldplay on repeat and reading. I read a lot.

Mom used to make fun of me for it. “Your nose is always stuck in a book,” she’d say, rolling her eyes. It wasn’t just books, though. I’d read magazines, newspapers, pamphlets, anything that was lying around. And I’d retain most of the information, without really trying.

Mom liked that part. She’d have me recite on cue—to friends (which she didn’t have many of) and to boyfriends (which she had too many of)—weird knowledge that I had collected over time. Like the fact that superb fairy wrens are the least faithful species of bird in the world, or that the original pronunciation of Dr. Seuss’s name rhymed with “Joyce,” or that Leonardo da Vinci invented the first machine gun (which shouldn’t really surprise anyone, since he invented thousands of things).

Then she’d beam and shrug her shoulders and give a smile and say, “I don’t know where she came from.” And I’d always wonder if that maybe was a little bit true, because every time I got the nerve to ask about my father—like, what his name was, for instance—she’d snap and say something like “What’s it matter? He’s not here, is he?”

Basically, I was a freak show growing up. And not just because I didn’t know who my father was or because I could recite random facts. I’m pretty sure neither of those are unique characteristics. It was because of my condition, which is how people referred to it: a condition. And my condition was the reason my desk in elementary school had to be at least eight feet away from the others. And why I had to sit on a bench by myself at recess and watch while kids created trains out of their bodies on the slide and played red rover and swung effortlessly on monkey bars. And why my body was clad in long sleeves and pants and mittens—cloth covering every square inch of skin on the off chance that the kids I was kept so far away from accidentally broke the boundaries of my personal bubble. And why I used to stare openmouthed at mothers who would squeeze their children’s tiny bodies with abandon at pickup, trying to remember what that felt like.

Anyway, combine all the facts—my condition, the boy-kissing-me- and-my-almost-dying incident, my mother leaving—and voilà! It’s the perfect recipe for becoming a recluse.

Or maybe it’s none of those things. Maybe I just like being alone.

Regardless, here we are.

And now, I fear that I’ve become the Boo Radley of my neighborhood. I’m not pale or sickly looking, but I’m afraid the kids on the street have started to wonder about me. Maybe I stare out the window too much when they’re riding their scooters. I ordered blue panel curtains and hung them on each window a few months ago, and now I try to stand behind them and peek out, but I’m worried that looks even more creepy, when I’m spotted. I can’t help it. I like watching them play, which I guess does sound creepy when I put it like that. But I enjoy seeing them have fun, bearing witness to a normal childhood.

Once, a kid looked directly into my eyes and then turned to his friend and said something. They both laughed. I couldn’t hear them so I pretended he said something like, “Look, Jimmy, it’s that nice, pretty lady again.” But I’m afraid it was more like, “Look, Jimmy, it’s that crazy lady who eats cats.” For the record, I don’t. Eat cats. But Boo Radley was a nice man, and that’s what everybody said about him.

THE PHONE IS ringing. I look up from my book and pretend to contemplate not answering it. But I know I will. Even though it means getting up from the worn indent of my velvet easy chair and walking the seventeen paces (yes, I’ve counted) into the kitchen to pick up the mustard-yellow receiver of my landline, since I don’t own a cell phone. Even though it’s probably one of the telemarketers who call on a regular basis or my mother, who only calls three or four times a year. Even though I’m at the part in my book where the detective and the killer are finally in the same church after playing cat and mouse for the last 274 pages. I’ll answer it for the same reason I always answer the phone: I like hearing someone else’s voice. Or maybe I like hearing my own.

Riiiiiiiinnnnng!

Stand up.

Book down.

Seventeen paces.

“Hello?”

“Jubilee?”

It’s a man’s voice that I don’t recognize and I wonder what he’s selling. A time-share? A new Internet service with eight-times-faster downloads? Or maybe he’s taking a survey. Once I talked to someone for forty-five minutes about my favorite ice-cream flavors.

“Yes?”

“It’s Lenny.”

Lenny. My mother’s husband. I only met him once—years ago, in the five months he and my mother were dating before she moved out to Long Island. The thing I remember most about him: he had a mustache and pet it often, as if it were a loyal dog attached to his face. He was also formal to the point of being awkward. I remember feeling like I should bow to him, even though he was short. Like he was royalty or something.

“OK.”

He clears his throat. “How are you?”

My mind is racing. I’m fairly certain this isn’t a social call since Lenny has never called me before.

“I’m OK.”

He clears his throat again. “Well, I’m just going to say it. Victoria—Vicki—” His voice breaks and he tries to disguise it with a little cough, which turns into a full-on fit. I hold the receiver with both hands to my ear, listening to him hack. I wonder if he still has a mustache.

The coughing spell over, Lenny inhales the silence. And then: “Your mother died.”

I let the sentence crawl into my ear and sit there, like a bullet a magician has caught with his teeth. I don’t want it to go any farther.

Still holding the receiver, I put my back against the wallpaper covered in cheerful pairs of red cherries and inch my butt down until I’m sitting on the cracked and tattered linoleum, and I think about the last time I saw my mother.

She was wearing a two-sizes-too-small mauve sweater set and pearls. It was three months after the Boy Kissed Me and I Almost Died, and as I mentioned, I had spent the summer mostly in my room. But I also spent a considerable amount of time shooting daggers at my mother whenever I passed by her in the hallway, seeing as how the whole incident would never have happened if she hadn’t moved us from Fountain City, Tennessee, to Lincoln, New Jersey, three years earlier.

But honestly, that was the least of her sins as a mother. It was just the most recent and most tangible to be angry with her for.

“It’s the new me,” she said, twirling at the bottom of the stairs. The movement caused the cloying scent of her vanilla body spray to waft through the air.

I was sitting in the velvet armchair rereading Northanger Abbey and eating Thin Mint cookies from a plastic sleeve.

“Doesn’t it just scream millionaire’s wife?”

It didn’t. It screamed slutty June Cleaver. I looked back down at my book.

I heard the familiar crinkling of cellophane as she dug in her back pocket for her pack of cigarettes, and the click of the lighter.

“I’m leaving in a few hours, you know.” She exhaled and slid onto a couch cushion across from me.

I looked up and she gestured toward the door at the one suitcase she had packed. (“That’s all you’re taking?” I had asked that morning. “What else would I need?” she said. “Lenny’s got everything.” And then she giggled, which was just as strange as her wearing pearls and a sweater set and twirling.)

“I know,” I said. Our eyes met, and I thought of the night before, as I lay in bed and heard the door to my room softly creak open. I knew it was her, but I remained still, pretending to sleep. She stood there for a long time—so long that I think I drifted off before she left. And I didn’t know if it was my imagination, or if I really did hear her sniffling. Crying. Now I wondered if maybe there was something she was trying to muster up the courage to say, some profound mother-daughter moment. Or at least an acknowledgment of her poor mothering skills where we’d laugh and say something banal like “Well, at least we survived, right?”

But sitting on the couch, she just inhaled her cigarette again and said: “So, I’m just saying, you don’t have to be so bitchy.”

Oh.

I wasn’t sure how to respond to that, so I took another cookie out of the sleeve and put it in my mouth and tried not to think about how much I hated my mother. And how hating her made me feel so guilty that I hated myself.

She sighed, blowing out smoke. “Sure you don’t want to come with me?” she said, even though she knew the answer. To be fair, she had asked multiple times over the past few weeks in different ways. Lenny has plenty of space. You could probably have a whole guesthouse to yourself. Won’t you be lonely here all by yourself? I laughed at that last one—maybe it was some innate biology of being a teenager, but I couldn’t wait to be away from my mother.

“I’m sure,” I said, flipping a page.

We spent the last hour we’d ever spend together in silence—her chain-smoking, me pretending to be lost in my book. And then when the doorbell rang, announcing the arrival of her driver, she jumped up, patted her hair, and looked at me one last time. “Off I go,” she said.

I nodded. I wanted to tell her that she looked nice, but the words got caught in my throat.

She picked up her suitcase and left, the door easing shut behind her.

And there I sat, a book in my la...