![]()

Trees and cities

THE ALDERS

Common alder | London, Venice

Italian alder

THE ASHES

Common ash | Glasgow

Raywood ash

THE BEECHES AND A BEECH-LIKE TREE

Common beech | London

Copper beech

Hornbeam

THE BIRCHES

Silver birch | Lancaster, London

Himalayan birch

THE BUTTERFLY BUSHES AND ANOTHER URBAN UPSTART

Buddleja davidii | London

Leyland cypress

THE CHERRIES AND ANOTHER FLOWERING FRUIT

Wild cherry | Hiroshima, London

Crab apple

THE ELDERS AND OTHER TREES CELEBRATED BY HERBALISTS

Common elder | London

Lime and pine

THE ELMS

English elm | Brighton

Wych elm

THE FIGS AND ANOTHER FLESHY FRUIT

Common fig | Sheffield

Mulberry

THE HAZELS

Common hazel | Leeds

Turkish hazel

THE HORSE CHESTNUTS

Horse chestnut | London, Amsterdam

Sweet chestnut

THE LIMES

Common lime | Berlin, Vienna

Silver lime

THE MAIDENHAIRS AND ANOTHER BULLETPROOF TREE

Ginkgo biloba | London, Hiroshima, New York

Caucasian wingnut

THE MAPLES

Sycamore | London, Edinburgh

Norway maple

THE OAKS

English oak | London, New York

Red oak, holm oak and pin oak

THE PINES AND ANOTHER CONIFER

Maritime pine | Bournemouth

Dawn redwood

THE PLANES AND ANOTHER TOUGH STREET TREE

London plane | London, Milton Keynes

American sweet gum

THE POPLARS

Black poplar | Manchester

Lombardy poplar

THE TREES OF HEAVEN AND ANOTHER LARGE-LEAVED EXOTIC

Tree of heaven | New York, London

Indian bean tree

THE WHITEBEAMS AND ANOTHER SORBUS

Bristol whitebeam | Bristol

Rowan

THE YEWS AND ANOTHER MEDICALLY SIGNIFICANT TREE

English yew

Willow

LEAF GUIDE

Common alder p.18

Common ash p.26

Common beech p.36

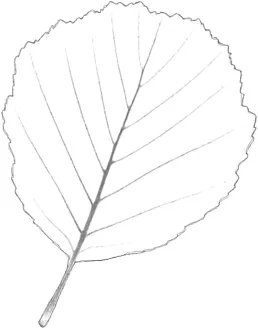

Silver birch p.46

Butterfly bush p.56

Wild cherry p.64

Common elder p.76

English elm p.88

Common fig p.98

Common hazel p.106

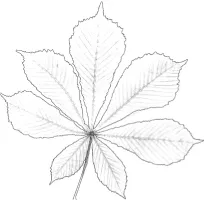

Horse chestnut p.116

Common lime p.126

Ginkgo p.134

Sycamore p.142

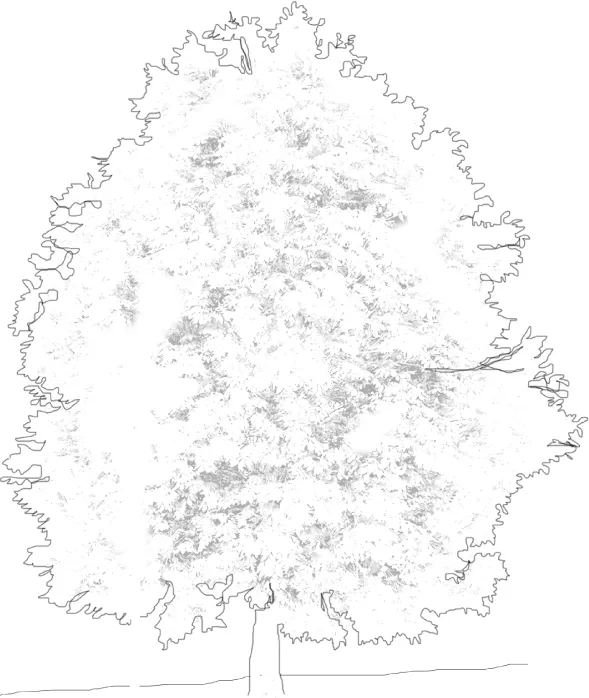

English oak p.152

Maritime pine p.164

London plane p.176

Black poplar p.186

Tree of heaven p.196

Bristol whitebeam p.204

English yew p.214

The alders

There are several different types of alder tree – around thirty – and all of them enhance soil fertility. They also all have catkins and small, woody, cone-like fruits, which together make alders easy to pick out from other trees, especially in winter when they have lost all their leaves.

COMMON ALDER

Alnus glutinosa

‘Alnus’ means red, which refers to the fact that alder wood ‘bleeds’ when cut, turning red on exposure to the air; ‘glutinosa’, meanwhile, reveals that this tree has buds and young leaves that are sticky.

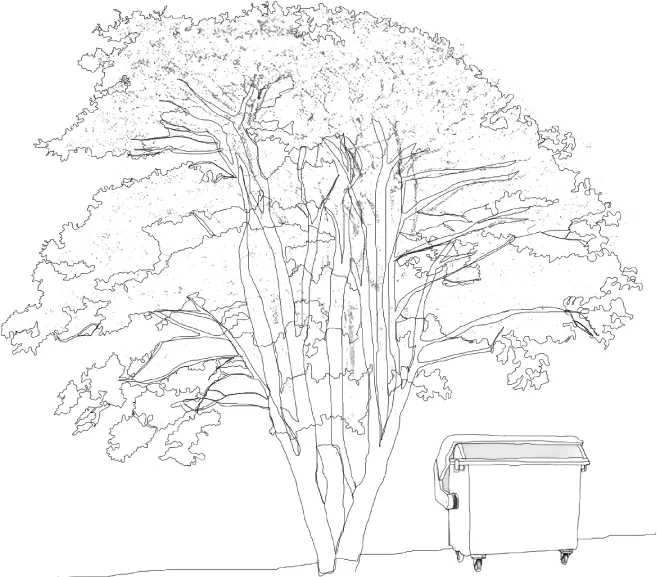

Shape is slender and conical, becoming more straggled with age. (Fig. 1)

Leaves are dark green, round and leathery; never pointed, but sometimes indented at the tip. (Fig. 2)

Bark is grey-brown and finely fissured.

Flowers are drooping purplish catkins (male), erect green catkins (female), both on the same tree.

Fruit are small, woody cones stuffed with tiny seeds. (Fig. 3)

Found by water and marshy ground, as well as in landfill sites and reclamation projects.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

It’s winter in the sylvan city and most of the trees are bare. From afar they look gaunt, absent even – tree-shaped holes cut out of the greyscale sky. Up close, they’re as solid as ever, their dark trunks rimed with wet. Early, on the coldest mornings when your hands ache and your breath billows out of you like smoke, the trees’ high-up branches flash and crackle with frost. While this might not be the obvious season to begin a journey through the urban forest, some trees have traits at this time of year that set them apart from the rest. The alder is one of them.

It was a February afternoon of insistent drizzle when I first learned how to pick alder out from a crowd. The day was melancholy but mild, requiring wellington boots and waterproofs rather than gloves and a hat. I was walking in Wick Wood beside the canalized River Lea, on the outer edges of Hackney in east London. Once known as Wick Field, this was planted into a small community woodland in the late 1990s. I didn’t have a route mapped out around the wood. I’d exited my floating canal-boat home with no plan other than to stretch out my sea legs and unbend my body. It was dripping overhead and soft underfoot, and the air inside the wood seemed moister than outside it. There’s always white noise in a city – traffic, industry, people – but in Wick Wood it was quiet. Even without their leaves, the close-packed trees and shrubs formed a soundproof barrier between me and the world beyond.

Everything seemed dormant or dead, so it was a surprise when I came upon a tree that was free of leaves, but busy with birds. The birdwatcher camping out in an adjacent bush made sense, as there was plenty to see. He explained that the birds were siskins and the tree was an alder, a species beloved for the cone-like, seed-packed fruits it wears all through winter. Looking at the tree, I could see that it was indeed studded with tiny, woody cones and I knew this was unusual – as a rule, cones are found on conifers or cone-bearing firs, trees that tend to keep their leaves all year round. The naked alder was clearly not an evergreen, and so these cones were a feature that made it stand out.

The common alder is deciduous or broadleaved, which means it sheds its leaves in autumn and grows new ones in spring. Revisiting Wick Wood a few months later, I learned that alder leaves are distinctive: dark green, rounded, almost the shape of a tennis racket, sometimes with a gentle indent at the tip. But it’s definitely when the alder loses them that it is easiest to spot. Shaking off its leathery summer coat, the tree reveals that its branches have become covered in flowers. It’s not blossom, in the apple or cherry-tree sense, but rather that the tree is decked with drooping, purplish catkins and upright, green ones, which eventually ripen into those telltale dark-brown cones. Legend has it that Robin Hood’s camouflaging outfit was dyed using a green pigment made from these blooms. The drooping catkins are male, the upright ones female. Like many of the species we’ll meet in the urban forest, flowers of both sexes grow on the same tree, making the alder ‘monoecious’, or a hermaphrodite.

It’s neat that the alder sits at the beginning of this alphabetically organized book, because where it grows marks the start of a new story. It may be relatively short-lived – it averages about sixty years, where some trees, like the yew, can live for centuries – but it does a lot for us in its lifetime, and even after its death. Like all plants, alder photosynthesizes – this invisible process not only provides fuel for the plant, but is also responsible for the oxygen, food, fibres, medicines and timber that we need to live.

What makes the alder different is that it’s a pioneer, one of a small number of tree species that prepares the way for future forests. It uses the carbohydrates produced during photosynthesis in a very particular way – it provides its self-made sugars to bacteria that live on its roots. In turn, the bacteria absorb nitrogen from the atmosphere and provide it to the tree. In this way, the alder and its ally feed each other, at the same time cleansing the air of pollutants and enriching the earth with nutrients, clearing the way for other varieties of tree to take root. The alder’s ability to improve air and soil quality in this way makes it an urban hero, and landscape architects call on it when they have contaminated land to reclaim. ‘Phytoremediation’ is a way of using plants to restore balance, and an abandoned site might be planted with alders as part of its transformation from industrial to recreational.

Alder has a close connection with water too, and the fact that I found my first one growing in the urban but also riparian Wick Wood makes a lot of sense. It’s able to grow close to watercourses and in waterlogged ground because, as well as hosting those special nitrogen-fixing bacteria, alder roots have a system of air ducts that allow oxygen to flow, even underwater. These roots can also act like underground scaffolding and prevent soil erosion, and water-tolerant alder is planted along with willow to help keep riverbanks intact. No wonder the poet Kathleen Jamie turns to the alder in an ‘age of rain’, seeking advice on ‘a way to live on this damp ambiguous earth’ in her poem named after the tree.

It’s not only in life that the alder is heroic – once it is felled for timber, alder wood is soft and porous, and is only durable when kept wet. Rather than rotting, this timber is most effective when it’s waterlogged, which is why much of Venice is built on alder piles cut from strong tree trunks. As Italo Calvino suggests in Invisible Cities, ‘Nothing of the city touches the earth except those long flamingo legs on which it rests.’ Alder is part of Venice’s strength and support. It helps to hold the city in place.

ANOTHER ALDER WORTH KNOWING

In the Collins Tree Guide – an essential reference book for any tree-lover – dendrologist Owen Johnson describes the Italian alder (Alnus cordata) as ‘a plant with vigour and polish’. It’s fast-growing, capable of reaching twenty-five metres, where the common alder can usually achieve just twenty metres. It has conspicuous catkins in winter that can be up to ten centimetres long, and its large cones are red before they turn brown. The Italian alder also has glossy, heart-shaped leaves, smooth grey bark and a tidier, more slender shape. It comes into leaf early and loses that foliage late. It’s heat-, drought- and pollution-tolerant, making it a popular choice for urban streets, car parks and shelter belts.

The ashes

The ashes are a large, widespread group of trees – or ‘genus’ – possibly more than sixty members strong. Ash trees are usually male or female, but sometimes they swap sex or are both. All of them have compound leaves made up of leaflets arranged along a central stalk, and produce seeds enclosed inside a papery wing. These hang in bunches on the trees throughout winter, long after the leaves have been shed.

COMMON ASH

Fraxinus excelsior

Both ‘ash’ and ‘fraxinus’ stem from words meaning spear. This makes sense, as ash wood is strong and elastic, and was once an important material for making weaponry.

Shape is large but slender, with a rounded crown, a long, straight trunk and open, arching branches. (Fig. 4)

Leaves are compound, with elliptical, toothed leaflets arranged in opposite pairs along the leaf stem. (Fig. 5)

Bark is pale grey, darkening and splitting with age.

Flowers are sexually ambiguous; small purple and green tufts burst open at the tip of the twig.

Fruit are seeds enclosed inside a narrow wing, which ripens from green to light brown. (Fig. 6)

Found in parks and city streets, including in Glasgow.

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

The first tree to lose its leaves in autumn and the last to re-clothe...