eBook - ePub

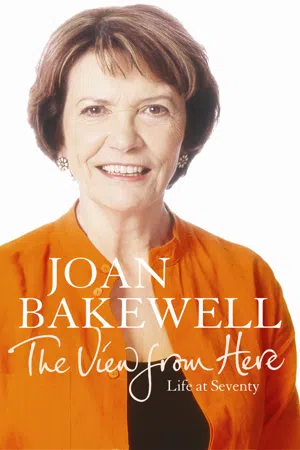

The View from Here

About this book

Built loosely on her much-loved Guardian column - Just 70 The View from Here is Bakewell's discerning and heartwarming account of life at 70 and beyond. A household name and a popular radio and TV broadcaster, Bakewell is the ideal ambassador for challenging what being 70 can mean for women today. All of life, including the taboos of old age, are here - work, family, love, sex, body and death - written about with humour, warmth, and Bakewell's characteristic verve and intelligence.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

Today

'For age is opportunity no less

Than youth itself, though in another dress,

And as the evening twilight fades away

The sky is filled with stars, invisible by day.'

Than youth itself, though in another dress,

And as the evening twilight fades away

The sky is filled with stars, invisible by day.'

HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW

ONE

A Place Called 'Old'

PREPARE TO BE OLD, to be very, very old. Projections made early in 2006 promise that many more of us will live to be a hundred. Some ten thousand do so already; indeed, the question arises of whether, twenty years hence, the Queen will be sending herself a congratulatory card. The number of centenarians could increase tenfold in the next sixty-eight years. By 2074 there could be 1.2 million people over one hundred. According to that admittedly speculative calculation anyone now in their thirties has a one in eight chance of reaching that age. So how do we view the prospect? I have in recent years hit the problem head on, writing about my own age and ageing in regular articles that to my delight have prompted an enthusiastic response, proof if it were needed that the old are still engaged in ideas and eager to exchange them. This book collects and extends some of those ideas, giving them a more recent perspective and adding others that have occurred to me. Each day seems to bring new experiences and insights that are just not available to those who haven't travelled this far in life.

To most people old age is a bad smell, a nasty place of bedpans and stair lifts, of bleak care homes and nurses who call you 'love' and 'dear' simply because to them all old people are alike. The public image of age is grim too, reinforcing a cosy contempt: too much 'grumpy, old' this and that, and songs that ask, 'Will you still love me when I'm sixty-four?' while expecting the answer 'no' of course. Headlines that harp on pensions, euthanasia and neglect may be justified but they aren't the whole story. I know plenty of old people living feisty and fulfilling lives. My oldest friend, aged ninety-seven, is currently enjoying the writing of Gabriel García Márquez and no, she isn't a graduate or a middle-class professional. She's simply a very intelligent woman whose humdrum life hasn't inhibited the use of her wits. I like to think there are many like her; it's a condition I aspire to in the coming decades.

We need, each and every one of us, an entirely new attitude to being old. It is, after all, the destination we deliberately set out for, the result of all those diets and exercise crazes, the purpose of the acres of health advice and food labelling. It's the natural outcome of flu jabs and health and safety inspections. What was it all for if not to live longer and remain fit? We are living in a far healthier world, a cleaner environment than in my grandmother's day. At the turn of the twentieth century the average life expectancy for a man was forty-five and for a woman forty-eight. How far we have come is nothing short of miraculous. Science has helped and is going on helping; stem cell technology is now at the threshold of developing body part replacements than can keep us regularly repaired. Body MOTs are not out of the question. We are living through a quiet revolution that is transforming the trajectory of our lives.

And in old age we are reaping the fruits: not a sudden lurch into a smelly decline, but vistas of years ahead of modest pleasures; horizons that are no longer set by the needs of family, the career ambitions, the immediate and intense business of daily survival. Hip replacements, cataract operations, heart pace-makers are rendering us active, even spry. As someone in the lower foothills of old age, I can bear witness to the abundance of energy and enthusiasm waiting to be used by people in their sixties and seventies. The University of the Third Age flourishes. The Open University is full of oldies. Literary festivals throughout the summer are thronged with grey-heads keen to know and question, learn and debate. 'Learning for life', a government slogan, now extends well after retirement. In their leisure time, the old aren't just boozing and cruising: the hardier spirits are climbing mountains, visiting the Pole, meeting sponsored challenges. I have a friend in his late seventies who has recently taken up tap-dancing. How's that for bravura!

People in power who now decide how we live need to be more aware of how the culture is shifting. As more live longer the changes can only accelerate. Even the young need to look beyond the stereotypes. Little Britain may be funny but it's sometimes also insulting. 'Old' is not another country, a place you're shunted off to when the real business of life is done, where you're parked in the ante-room of death and live in expectation of its imminent arrival. It is an era, as vividly a part of living as any other. It may be situated at the other extreme from youth but being old is not being ill. Life can be as full of value and delight, of incident and insight, as it is for a twenty-year-old. And now every twenty-year-old is likely to arrive there eventually.

The sudden watershed of retirement will have to be modified. There must be more varied and adaptable options than simply working full tilt until sixty, then slamming the door on all your wisdom and experience. We shall all certainly have to work longer. The whole economic house of cards will collapse unless we do. But that doesn't mean we have to stay in the rat race, with the stress and competitive thrust that gives middle age its ulcers. We need to plan for part-time, less hectic working lives, in jobs that society needs and welcomes, yet in which we also feel needed and valued.

The numbers of friends and contemporaries will thin out as the years go by. Death takes its toll in the face of even the most optimistic statistics. So we will need to stay close and grow closer. Families, local friends and neighbours will take the place of business colleagues and working contacts in their daily importance. At the same time, old friends across the globe can now be in touch via the internet. I have had more contact with old school chums in the last ten years than in any earlier decade. Yet it is also a time for the different generations to get to know each other. The existence of those apparent barriers that keep them apart – text jargon, say, or crazy clothes – can't be denied, but the two sides can be teased into some mutual respect. And the dangers of depression and stoic resignation that plague the lonely can't be ignored. I'm not saying old age is a bed of roses. But now we're all going there, let's fix it so we enjoy the journey.

THINGS WERE SO DIFFERENT IN my grandmother's day. She was born in the 1870s and when she had her seventieth birthday in 1947 I wrote a poem in honour of her great age. I was a gym-slipped schoolgirl at the time, much in love with Tennyson and Browning, and the embarrassing lines of my rhyme bear the unhappy traces of their influence. I speak of the 'flame of youth' – that's what she'd lost, and 'life's dwindling rays' – that's all she had left. The whole was written out in faultless copperplate, lending dignity to its callow sentiments. The tone was elegiac, giving thanks for a life dutifully spent and now nearing its end. It wasn't; she would live to be eighty-six, but to a child she seemed ancient at seventy, a stooped, white-haired figure crippled by rheumatoid arthritis, walking with two sticks.

Years roll by and it was recently my turn to hit threescore years and ten. Seventy: an ominous number by any reckoning, but nowhere near as bleak as in my grandmother's day. In my turn I duly received a clutch of spirited home-made cards from my grandchildren, admittedly younger than my pious thirteen-year-old self. No copperplate now, no tone of slightly fearful respect. Instead my greetings – conflating the graphic freedoms of artists Cy Twombly and Bridget Riley – were an uninhibited riot of colour, with the casually expressed wish, by one of them, that I should 'have a good day at the beach'. As indeed I did. How times have changed.

Seventy years: landmarks don't come any heavier than this. We giggled at thirty, with mock angst at saying goodbye to youth, but sharply aware that we were coming into our prime. At forty we glowed with busy lives going well or frowned with doubts as the options narrowed; we called it early middle age. We preened at fifty with some things well done and mistakes made and buried; we laughed at sixty in the warmth of a lifetime's circle of friends. Those of us who go through life keeping in touch, never quite leaving behind each era, probably had the greater reach. But most of us have that close-knit group of around a dozen or so whom we keep close. And surely this was still late middle age. But at seventy there's no denying that even by the most generous reckoning, it's the beginning of getting old. And note how even now I'm pretending it's merely the antechamber to age.

For the ominous day itself, I tried going into denial. I tried to pretend it wasn't happening. No party this time round. Instead, I fled the country. I went to France for a week with the immediate family, disguising it as little more than an Easter holiday. Easter – a moveable feast – has always been entwined, via ancient calendars and phases of the moon, with my actual birth date. Jesus may have returned to earth from the dead on Easter Day, but it was on Easter Day that I first arrived. What's more, I was christened at Pentecost, so I feel that the Church's celebrations have me in their shifting grasp.

Here I am reaching that age so particularly marked in the Old Testament, with its resounding threescore years and ten. But there's hope within its pages too. It's here that Methuselah lived to be 969 years, fathering his son Lamech when he was 187. His father Enoch lived to be 365 and his grandson Noah 950. All of their forebears lived for between 895 and 962 years, filling the gaps needed to trace the line of Joseph, Jesus's father, back to Adam and hence God, who is older than time itself. Quite what religious fundamentalists who believe in the literal truth of the Bible make of these statistics I don't know. But perhaps they show that even in Judaic times when mortality rates were low – what with famines and plagues and such – certain people lived to a great age, though none of them appears to have been female. So not much comfort there.

Today we have bright modern statistics of our own. In the developed world, life expectancy has been increasing steadily since the 1840s. Currently women are living longest in Japan, on average until they reach the age of 84.6; France is nearly as good with 82.4. In Britain life expectancy for a woman is 79.9. Because I've survived thus far, my own is something more than that, though not by much. Not surprisingly, for me these figures have ceased to be mere statistics. At what point, I wonder, do I begin to reckon on just ten more springtimes, ten more Christmasses? Can I, medical prognoses being what they are, estimate the ages my grandchildren will be when I reach the final shore? That way I can scare myself silly into, you might say, an early grave. But it's no way to have a life. After all, at the age of eighty-one my father bought a brand-new car, giving up his ageing Rover for a foreign model. He was of a generation who, ever since the war, had refused to buy either a Japanese or a German car. 'I don't forget what they did to Ernie Edge in that prison camp,' he would explain. Now here he was, finally moving on and conceding that world trade had superseded even the most legitimate grudge. He also regularly played nine holes of golf a day, skirting the other nine, to meet up with friends at the reassuring nineteenth. His mix of healthy exercising and cheerful socializing seems to me an excellent way to live. I hope I have inherited his optimism. Perhaps there's something in my psyche that is editing out the future finality, and leaving me no older than I feel.

Certainly, at the age of ninety-six, the Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer created a wonderfully designed pavilion for London's Serpentine Gallery. In the same week in 2003 the then Tory Chairman Theresa May, when asked in some glossy questionnaire 'When is it too old to wear a micromini?', replied: 'Probably sixty, though if you have the legs, go for it.'

Which leaves me considering several options: I can convert to Judaism and claim ancient lineage; move to Japan to join their statistics; train as a New World architect; or buy a micromini. Suddenly I feel that in my seventies life still has lots of possibilities.

ORCHESTRAL CONDUCTORS MUST take the same approach. They don't have a problem with age. If they are any good, the world assumes that they will go on being good. The words 'mellow', 'wisdom' and 'experience' feature in reviews of their concerts. Toscanini and Klemperer conducted well into their eighties; Leopold Stokowski gave concerts in his nineties. In my own day Bernard Haitink continues at the helm of the Dresden Staatskapelle in his seventy-sixth year. Charles Mackerras's eightieth birthday celebration concerts continue into 2006. Both remain the toast of critics and audiences love them. No age discrimination there, then.

Nor do we expect conductors to retain their youthful looks: Simon Rattle's tousled locks gave him a boyish charm when he was younger. Now that those tousled locks are grey they bestow a certain eccentric gravitas. Such looks go down well with all who love his work. Pierre Monteux went on conducting the London Symphony Orchestra well into his late eighties, towards the end perched on a stool and making minimal movements. From Monteux we don't expect flamboyant gestures, merely wonderful music, which he regularly delivered.

There was another prominent grey head, recently conspicuously displayed on a number of billboards around the country. It was that of an elderly man, faceless and anonymous, his grey hair thinning, displayed below the message: 'Ignore this poster: it's got grey hair.' And the strapline: 'Ageism exists: help us put a stop to it.' This was a campaign run by Age Concern to tackle what it believes is the last form of legal discrimination and it's begun to have an effect. It has, until now, always been perfectly legal to sack someone for being old. A routine retirement age of sixty had the force of employment legislation. However, new age discrimination regulations, coming into force in October 2006, set a new default retirement age of sixty-five. Compulsory retirement below sixty-five will still be allowed but only if it can be objectively justified and an employer must inform the employee between six and twelve months before the intended date of retirement and give them the opportunity to request to continue working if they so wish. By mid-March 2006 there was a massive response to union calls for strikes among public sector workers who resented the new directive that many of them would still have to work until sixty-five. It isn't everyone's ideal old age, just to go on working in a job that has become routine.

There are many paradoxes in the way our society sees the old. They are somehow regarded, if they're thought of at all, as a minority group who have problems with pensions and varicose veins. The image of them in the media and in advertising is often insulting and contemptuous. I blench every time I see film of aged couples ballroom-dancing in some church hall in what is obviously mid-afternoon. There's nothing wrong with their doing it, it's just that it's such an overused image by newsrooms as a quick shorthand for 'the old'. What about those mountaineers and hill walkers among us? Younger people need reminding that the over-fifties hold 80 per cent of the nation's personal assets. Forty per cent of the population is over fifty and that percentage is growing steadily. Many of us are actively working and there are plenty who resist the mandatory retirement age.

This image of each generation as it is held in the popular imagination is shaped and coloured particularly by the highly persuasive power of marketing and advertising. The di...

Table of contents

- Contents

- Introduction

- PART ONE Today

- PART TWO Yesterday

- PART THREE Tomorrow

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgements

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The View from Here by Joan Bakewell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Journalist Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.