![]()

CONTENTS

| Introduction |

1 | The Ancient World |

2 | Middle Ages Spread |

3 | Renaissance Men (and Women) |

4 | Darkness and Enlightenment |

5 | The Empires Strike Back |

6 | Oh, What Lovely Wars |

7 | Modern Times |

8 | Living in the Now |

| Index |

| Acknowledgements |

![]()

INTRODUCTION

What would the history of the world look like if you learned it all from watching movies? According to some of the films in this book, birth control pills have been available for 1,600 years; everyone in the Middle Ages could read, but William Shakespeare was illiterate; Scottish rebel Sir William Wallace managed to father King Edward III of England, even though he never met Edward’s mother and died seven years before Edward was born; Mozart was murdered by a jealous rival; champions of democracy have included the ancient Mauryan emperor Asoka, the nation of Sparta, Marcus Aurelius, Lady Jane Grey and Oliver Cromwell; the American war in Vietnam was awesome; all American wars were awesome; and a crew of plucky Americans including Jon Bon Jovi captured the first Enigma machine from the Nazis in World War II.

Unless you make an effort to read history books or watch high-quality television documentaries on historical subjects, the chances are that as an adult you will consume all your history from fictional feature films and television dramas. Maybe, if you paid attention in school, you’ll know they get some things wrong. But it will be difficult to stop deeper and broader misconceptions finding their way into your consciousness.

If you get it from the movies, your history of the world will be strongly focused on Western Europe and North America, and on the doings of white, heterosexual, Christian men of the upper classes. The women you know about will mostly be queens and mistresses, if they have characters at all beyond the ability to wear (and perhaps swiftly remove) sparkly, flimsy outfits. Even when you watch something about, say, ancient Egyptians, Mongols or Arabs, they will frequently be played by white people. Even if you watch films that are not made in Hollywood, this might still be true. In the Pakistani movie Jinnah (1998), Mohammad Ali Jinnah was played by Christopher Lee; in the Libyan movie Lion of the Desert (1981), Sharif al-Ghariyani was played by John Gielgud. Most historical characters will present themselves to you with a comforting simplicity, either as heroes or villains. Most historical stories will seem to have a satisfying beginning, middle and end. The good guys will mostly win, at least morally; for filmmakers know that if you leave the cinema uplifted or invigorated you will recommend the film to your friends. History onscreen becomes legend, myth, fable, propaganda.

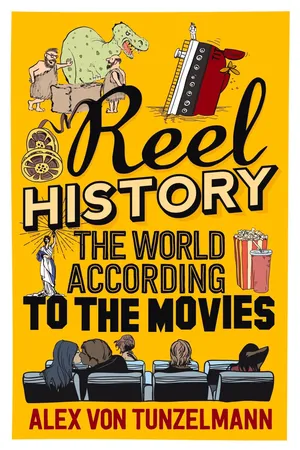

Since 2008, I’ve been the historian behind Reel History, a column on historical films for the Guardian’s website. Every week, I watch one, then try to work out how it relates to the truth of what happened – aware, of course, that truth itself is slippery and subjective. It’s not always a bad thing to learn about history from films. I’ve certainly broadened and deepened my knowledge by watching such fine examples as The Lion in Winter (1968), a razor-sharp Plantagenet comedy with Peter O’Toole as Henry II and Katharine Hepburn as Eleanor of Aquitaine; The Killing Fields (1984), a moving tale of Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge; Ran (1985), Akira Kurosawa’s synthesis of King Lear and the real story of sixteenth-century Japanese daimyo Mori Motonari; and Twelve Years a Slave (2013), Steve McQueen’s searingly brilliant retelling of the story of Solomon Northup. In all of these cases, and many more, filmmakers have taken resonant stories and told them within a setting of well-researched period detail which does not suffocate meaning but enhances it. They get the facts right, or approximately right; but they also go beyond a simple retelling of the facts to find poignancy, tragedy, drama or humour. These films have a feeling for their time, but also a sense of what matters in ours.

Many filmmakers go to great lengths in pursuit of accuracy. Historian Justin Pollard has consulted on films including Elizabeth (1998) as well as the TV series The Tudors and Vikings. He spent two years researching Vikings from primary sources. ‘We translate lines into Old Norse and Old English, use pre-Conquest missals for religious scenes and reconstruct locations and events from contemporary chronicles – inasmuch as that’s possible in the ninth century!’ he told me. ‘We do make mistakes but often what are called “mistakes” are conscious decisions made for reasons of budget, logistics or narrative, like compressing time frames, shooting in a different location to the actual event, or reducing the cast of characters.’

Reel History goes easy on such ‘mistakes’ that are really just storytelling choices. Real life doesn’t fit neatly into three-act structures, nor into the approximately 90–240-minute run-time of feature films. Most filmmakers working in a commercially driven industry have to work within these conventions. Restructuring stories to be more compelling and more easily understood is part of a screenwriter’s job.

Changes that have been made for deliberate comic effect don’t tend to get slapped down in Reel History either, if they’re funny. Greg Jenner was historical consultant to the terrifically enjoyable Horrible Histories TV series, beloved of many usually serious historians. ‘We had to balance the post-modern comic whimsy, complete with time-travelling devices and modern TV references, with communicating 4,000 historical facts, and then flagging up which were the jokes and which were the true bits,’ he says. ‘We had a puppet rat to do that.’ In one of my favourite semi-historical films, Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989), two Californian teenagers with a time machine establish that Napoleon is ‘a short dead dude’, Julius Caesar is ‘a salad-dressing dude’, and Genghis Khan is ‘a dude who, 700 years ago, totally ravaged China’. Some of us passed History GCSE with less. Jenner’s master’s thesis was on the reactions of medieval historians to films about King Arthur: ‘Everyone decided Monty Python’s Holy Grail was the best because it’s full of historical in-jokes.’

‘Humour is vital in helping us engage with the past,’ adds Professor Kate Williams, who presents history programmes on radio and TV. ‘Even if historical films are inaccurate, they get audiences involved.’ Justin Pollard agrees: ‘I hope historical drama serves as an inspiration for people to go and find out more. If you look at how well sales of popular Tudor history books did after The Tudors then I think that was the case.’

This is a very positive effect – but there is a darker side to some historical filmmaking. Many of the films in this book were made, officially or unofficially, for the purpose of advancing a specific political agenda. Some of these qualify as official propaganda, financed by governments or militaries; others are just trying to push a case because the filmmakers strongly believe it, whether that’s Roland Emmerich advancing his oddball Shakespeare conspiracy theories in Anonymous (2011) or Cecil B. DeMille bigging up McCarthyism in The Ten Commandments (1956). From Alexander Nevsky (1938) to Zero Dark Thirty (2012), some films are meant to influence the way we think.

Every week, somebody says to me: ‘It’s a fictional movie, not a documentary.’ Well, yes, of course it is – but some films deliberately blur the line. Paul Greengrass’s United 93 (2006) and Oliver Stone’s JFK (1991) both use a documentary style to present heavily fictionalized – and heavily politicized – historical cases. Even in less overtly political films, the versions of history shown often have a substantial and long-lasting impact. The iconic cultural images of such figures as Henry VIII, Robin Hood and Richard III were set by The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933), The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and Laurence Olivier’s production of Richard III (1955) respectively. The myth that Jewish slaves built Egypt’s pyramids – controversially repeated by Israeli politician Menachem Begin in the twentieth century – does not appear in the Bible and is a historical impossibility: the great pyramids were built before Judaism existed. Yet it has been cemented in many people’s minds by generations of fanciful Hollywood movies about Moses. The myth that galley slaves were the norm in the Roman Empire can largely be traced to Ben-Hur (1959). The myth that Vikings wore helmets with two horns stems from the costume designs for the 1876 Bayreuth opera festiv...