eBook - ePub

Grassroots Leadership and the Arts For Social Change

- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Grassroots Leadership and the Arts For Social Change

About this book

Throughout history artists have led grassroots movements of protest, resistance, and liberation. They created dangerously, sometimes becoming martyrs for the cause. Their efforts kindled a fire, aroused the imagination and rallied the troops culminating in real transformational change. Their art served as a form of dissent during times of war, social upheaval, and political unrest. Less dramatically perhaps, artists have also participated in demonstrations, benefit concerts, and have become philanthropists in support of their favorite causes. These artists have been overlooked or given too little attention in the literature on leadership, even though the consequences of their courageous crusades, quite often, resulted in censorship, "blacklisting," imprisonment, and worse. This forthcoming book seeks to explore the intersection of grassroots leadership and the arts for social change by accentuating the many victories artists have won for humanity. Through this forthcoming book readers will vicariously experience the work of these brave figures, reflect on their commitments and achievements, and continue to dream a better world full of possibility.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Grassroots Leadership and the Arts For Social Change by Susan J. Erenrich, Jon F. Wergin, Susan J. Erenrich,Jon F. Wergin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Negocios y empresa & Liderazgo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Grassroots Leadership and Cultural Activists Part 1: Performance Art

CHAPTER

1

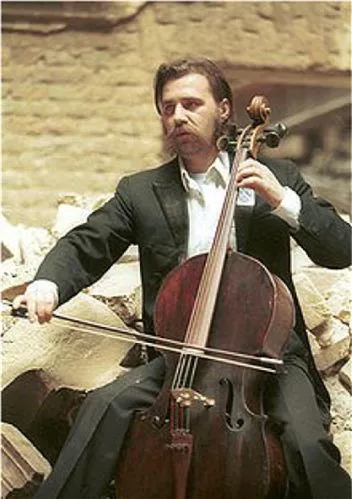

The Cellist of Sarajevo: Courage and Defiance through Music as Inspirations for Social Change

You ask me am I crazy for playing the cello?

Why do you not ask if they are not crazy for shelling Sarajevo?

Vedran Smailović (Keuss, 2011, p. 125)

On May 27, 1992, a grenade was thrown into a crowd waiting for bread at a bakery in Sarajevo, Bosnia–Herzegovina, killing 22 people and injuring many more. Bosnian cellist Vedran Smailović lived nearby and was horrified at the senseless slaughter as he helped the wounded and moved the dead. Still in shock, the next morning, Smailović dressed in a tuxedo, took his cello, walked to the crater created by the grenade, and played Tomaso Albinoni’s Adagio in G Minor in the rubble, despite gunfire and grenades exploding around him. He performed his musical vigil for 22 days to honor each of the victims. Then, for two years, he continued to play his cello in the streets, in bombed out buildings, at funerals, and in cemeteries. Smailović’s act of courage and defiance helped change the mood of Sarajevo from fear to determination; inspired at least three classical music pieces, a Christmas medley, several folk songs, a children’s book, several paintings and poems, and two novels; and secured his place among world peacemakers (Buttry, 2011). Smailović became a grassroots leader whose actions, along with those of other artists trapped in the siege, illustrated how art can catalyze social change.

In this chapter, we explore how the blend of music and intentionality manifested in Smailović’s leadership, together with the cultural productions of other artists, served to build a transformational global community that took a stand against the war. His and other artists’ defiance of the existing ideology of power and war helped to promote the international dialog of peace. We speak from the perspective of having lived through the war, either actually, in the case of one of the authors, or vicariously, in the case of the other. Our spirits hence resonate with the spirits of the grassroots artist leaders of the siege.

We argue that grassroots artist leaders trapped in war are unique in that their identity is that of performer–victim. The identity of the audience is, at the same time, that of spectator–victim. Such unusual blurred identities bring performer and audience into a merged unity so that they all become grassroots leaders defying the brutality of the reality around them and promulgating culture and civilization. Their actions as performers and spectators manifest courage and defiance. They magnify their chances of being targeted by participating in public, thus acting courageously, and defy the powers-that-be whose intent is to dehumanize and annihilate them. They speak a language distinct from the ongoing political narrative and it is this language that has the power to catalyze social change. Irony and surreal twists of the war reality through various artistic expressions are essential aspects of this language. They reveal truths hidden in situations and catalyze the global response that the world does not have to be this way after all. It is this realization that is the beginning of building a new more civilized world.

Bosnian War and the Siege of Sarajevo

Following the death of Tito in 1980, nationalist leaders who had been restrained during Tito’s rule began filling the leadership vacuum and making moves to declare their republics’ independence. Being a multiethnic state comprised of Muslim Bosniaks, Croatian Catholics, and Orthodox Serbs, Bosnia–Herzegovina was split about whether to declare independence. Fearful that they would become a minority and hence be marginalized in an independent Bosnia, the Bosnian Serbs wanted to remain in Yugoslavia. On October 24, 1991, Bosnian Serb members of parliament formed the Assembly of the Serb People of Bosnia and Herzegovina. On January 9, 1992 the Assembly established the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which they renamed Republika Srpska in August 1992 (Donia, 2006).

Despite the actions of the Bosnian Serbs, Bosnia declared its sovereignty on October 15, 1991; held a referendum for independence on February 29 and March 1, 1992; and declared independence on March 3, 1992 (Donia, 2006). Twelve European Communities and the United States recognized Bosnia–Herzegovina’s independence in early April 1992. Serbs responded violently and by the end of April, the siege of Sarajevo, which is officially said to have commenced on April 5, 1992, was in full force (Donia, 2006).

An estimated 13,000 Serbs surrounded Sarajevo (Donia, 2006). They cut off the water and electricity supplies to the city and took key positions around Sarajevo. Serb snipers began terrorizing the inhabitants of Sarajevo and killing people randomly while they were searching for scarce water and scarcer food, trying to survive by whatever means they could. Snipers were paid for each “hit” and paid more for killing children (Dizderevic, 2012). Being the longest siege of a capital city in modern warfare history, 13,962 people were killed, including 5,434 civilians. Almost all of the buildings in Sarajevo were damaged and 35,000 were completely destroyed (Dizderevic, 2012; Donia, 2006).

The Cellist of Sarajevo

The siege was in its infancy on May 27, 1992 when the grenade killed the 22 people waiting in line for bread and stirred Vedran Smailović into spontaneous action. Smailović was a cellist in the Sarajevo String Quartet and had also played for the Sarajevo Opera, the National Theater, and the Symphony Philharmonic Orchestra RTV Sarajevo. Born on November 11, 1956, the fourth of five children, he was born into a celebrated Sarajevan musical family (Gateway Baptist Church, n.d.). He was a colorful character, using the ‘Fijaker” traditional use of horses and traps as transportation and “creating a fiesta wherever he went” (Gateway Baptist Church, n.d., para. 1).

Smailović described the scene after the attack and his response in the children’s book Echoes from the Square (Wellburn, 1998):

In the first instant there was utter silence … shock … and then chaos! … Fearful screams, yelling, shouting, blood … People lay about … dead … and wounded. From my home I heard the cries for help. I dashed out and saw … intermingled masses of bodies … blood everywhere. Everyone was in shock. Some ran away, agony on their faces … some ran towards the massacre, trying to help the wounded. Then cars arrived with rescuers … to help those who were injured. … even some of the rescuers were hit by sniper fire ….

The whole town was filled with pain. I didn’t sleep that night, wondering why this had happened to these innocent people, my good neighbors and friends.

The next morning, I went out to look again … the area was adorned with flowers and wreaths. I had brought my cello, but I didn’t know what to play. Tears just slid down my cheeks as I thought about the people who had died. I opened the cello case and somehow … something guided me to begin playing. Part way through, I recognized what I was playing – Albioni’s “Adagio.” It had emerged as my musical prayer for peace.

When I finished I noticed that people had stopped to listen and cry with me. As I talked with them I realized that this healing music helped us all to feel better. It provided us with hope … I was afraid … Everybody who’s sane is afraid when there are bullets and shells in the air. But when I play, the darkness is lifted and I am able to show the world my other feelings. Music is love that connects people. My wish is for everybody to be able to share this. (pp. 27–29)

Smailović played the Adagio in G Minor (SukiChaos, 2009) as a tribute for each of the 22 victims on 22 sequential days and then went on to play for two years as the war worsened. As one source recounted (Gateway Baptist Church, n.d.), Smailović

would place a little campstool in the middle of the bomb-craters, and play a concert to the abandoned streets, while bombs dropped and bullets flew all around him. Day after day he made his unimaginably courageous stand for human dignity, for civilization, for compassion, and for peace. When this vigil had ended, he would go to the infamous “Lion Cemetery,” infamous, because of the snipers who would lurk there and pick off civilians as they came to bury or mourn their dead. In an act of fearless defiance bordering on madness, Mr. Smailović, beautifully dressed, braved sniper fire, to play for the dead, as though he could reach them; as though he could comfort them. As though protected by a divine shield, he was never hurt, though his darkest hour came when, taking a walk to stretch his legs; his cello was shelled and destroyed where he had been sitting. The news wires picked up the story of the extraordinary man, sitting in his white tie and tails on a camp stool in the center of a raging, hellish war zone – playing his cello to the empty air. (para. 6)

Adagio in G Minor

Smailović’s choice of Adagio in G Minor was a likely piece to express his shock, grief, and bewilderment and to pay tribute to the 22 who had been killed at the bakery. Often attributed to the 18th century Venetian master Tomaso Albioni (1671–1751), the adagio was composed in its entirety by 20th century musicologist Remo Giazotto (1910–1998). Giazotto copyrighted and published the adagio in 1958 as “Adagio in G Minor for Strings and Organ on Two Thematic Ideas and on a Figured Bass by Tomaso Albinoni” (Perrottet, 2013). Giazotto claimed to have obtained a tiny manuscript fragment from one of Albinoni’s trio sonatas shortly after the end of World War II from the Saxon State Library in Dresden, which had preserved most of its collection despite being firebombed. Giazotto said he developed the work based on the theme he discovered (Perrottet, 2013). The Adagio’s slow tempo and majestic sounds have served as the theme or background music in movies and television shows, and has been adapted to pop music by popular singers. The Adagio accompanied the tributes to British pop singer/songwriter Amy Winehouse who died in 2011 of alcohol abuse at the age of 27 (Stambeccuccio, 2011); and American rock singer/songwriter Jim Morrison of the famous 1960s rock band, the Doors, who died in 1971 in Paris in mysterious circumstances at 27 (Ama Lia, 2010). Also played at British Princess Diana’s funeral, as well as at the 2011 commemoration of 911 in the Catholic Church of the Holy Rosary in Manhattan, New York, the adagio elicits stalwartness and triumph in its languorous tones.

Artistic Response to the Cellist

MUSICAL RESPONSE

Broadcast on television and written about by several journalists covering the siege, Smailović’s story resonated around the world. In Seattle, a conceptual artist called Beliz Brother arranged a tribute to Smailović and Sarajevo. Twenty-two different cellists performed Albinoni’s Adagio on 22 successive days on a street in the city’s university district (Bock, 1992).

English pianist and composer David Wilde heard about Smailović’s action soon after. As Wilde wrote (n.d.),

the report by John Burns in the New York Times of his heroic musical declaration made an impact more immediate than any political statement up to that time. I first read about it on a train from Nuremberg to Hannover. As I sat in the train, deeply move, I listened; and somewhere deep within me a cello began to play a circular melody like a lament without end. (para. 1)

World-renowned cellist Yo Yo Ma played the composition on his solo album for Sony Classical (pelodelperro, 2009). Ma called Smailović “a real present-day hero whose spirit I greatly admire. His spontaneous act of courage can be an inspiration to us all. It shows that an individual can make a difference in the world” (Wellburn, 1998, n.p.).

British composer David Heath wrote a string quartet called “The Cellist of Sarajevo,” often played by Cilo Gould, Steve Morris, Gillianne Haddow, and Diane Clark (Heath, 2014). Both Wilde’s and Heath’s compositions are slow, languorous, and dark, expressing great sorrow and grief and the pain and horror that the victims of war must feel as transmitted to these composers. Heath’s composition is also dissonant with sounds similar to sirens and phrases from Albinoni’s Adagio in G Minor.

The band Savatage released an album Dead Winter Dead in 1995 that focused on the Bosnian war and a love story between a Serb boy and a Muslim girl. This love story was likely based on the true tale of the young lovers Serb Bosko Brkic and Bosniak Admira Ismic who were shot and killed on May 19, 1993, as they were trying to escape Sarajevo over a bridge now dubbed the Romeo-Juliet Bridge. The song on the album called Christmas Eve Sarajevo 12/24 was based on the story of Smailović. The song was rereleased in 1996 on the album Christmas Eve and Other Stories by the Trans-Siberian Orchestra, comprised of some of the members of Savatage (HeliasValinti, 2010). The band had heard an erroneous version of the cellist’s story that depicted him as an old, white-haired man who played Christmas carols in the rubble every night of the siege (Breimeier, 2003). As the band’s founder Paul O’Neill told a reporter (Breimeier, 2003):

It was just such a powerful image – a white-haired man silhouetted against the cannon fire, playing timeless melodies to both sides of the conflict amid the rubble and devastation of the city he loves. Some time later, a reporter traced him down to ask why he did this insanely stupid thing. The old man said that it was his way of proving that despite all evidence to the contrary, the spirit of humanity was still alive in that place. (para. 11)

In 2001, American folk singer-songwriter John McCutcheon wrote and sang “The Streets of Sarajevo” in honor of Smailović. McCutcheon wondered in his lyrics where Smailović could have found music in the middle of the madness of the siege and how he could be so kind while under attack (McCutcheon, 2009). Smailović eventually moved from Sarajevo to Ireland and began to collaborate with Irish folk sing-songwriter Tommy Sands. Together, they wrote “Ode to Sarajevo,” which is featured on their album Sarajevo/Belfast. Sands and Joan Baez sang the ode and Smailović played the cello accompaniment. The song’s refrain spoke of the global impact of the cellist’s action and how he inspired people everywhere who heard his story (Smailović, 2014a, 2014b)...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Section I Grassroots Leadership and Cultural Activists Part 1: Performance Art

- Section II Grassroots Leadership and Cultural Activists Part 2: Visual Art and Film

- Section III Grassroots Leadership, Participatory Democracy, and the Role of the Arts in Social Movements in the United States

- Section IV Theatre of the Oppressed as a Form of Grassroots Leadership

- Section V People Power, Community Building, and the Arts for Social Change

- Epilogue

- About the Authors

- Index