![]()

1

Ownership of Securities

The Problems Caused by Intermediation

LOUISE GULLIFER

I. Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to set the discussion in the papers in this volume, and at the Conference itself,1 into context. The discussion was wide ranging, but at its core was one single theme: how do we deal with the problems thrown up by the intermediated holding of securities? This chapter attempts to identify the major problems, particularly those which are discussed in this book, and to draw together the threads of the various arguments made.

If we go back far enough, ownership of securities was a relatively simple business. Securities could be divided into two sorts: bearer securities and registered securities. As a broad generalisation, debt securities were bearer securities2 and shares were registered. Bearer securities were embodied in a piece of paper, and the holder of that paper was the holder of those securities. Transfer was by delivery and, as the bearer securities were negotiable instruments, the bona fide purchaser recipient obtained good title even if that of the transferor was defective, and took the bearer securities free from any equities affecting them in the hands of the transferor. Registered securities were also represented by pieces of paper, but legal title was derived from the entry on the company’s register and paper was merely evidence of this. Both of these systems depended on the movement of pieces of paper, and, as volumes of securities and trading grew, this became expensive, cumbersome and slow.3 Furthermore, the need to register transfers of registered securities in the register kept by the company also slowed up trading. Methods of settlement which avoided the credit risk of a time gap between delivery and payment were developed, using electronic means of settlement, which could not operate if securities were still in paper form.4

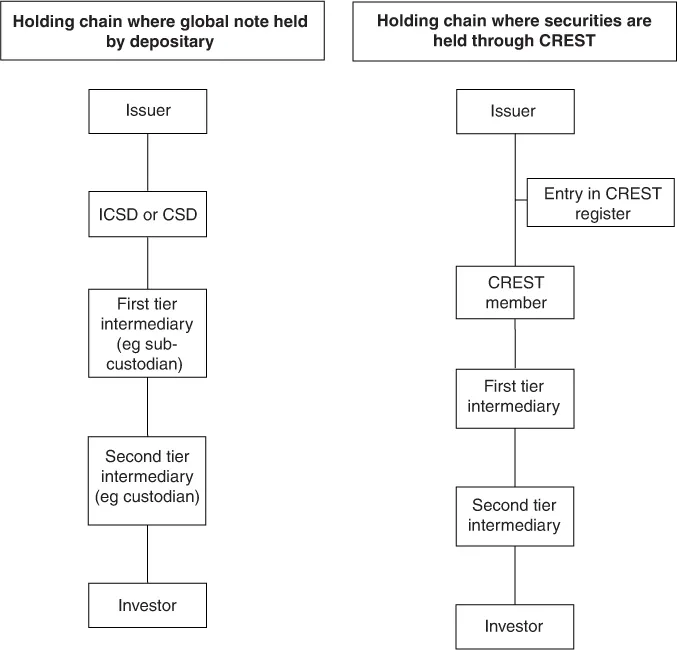

Two techniques were developed to deal with the problem of too much paper. One was to immobilise a global note, which represents the entire issue of securities,5 The global note or securities are then held by a central depositary who holds for one or more intermediaries, who then hold either for investors or for other intermediaries. The records of the intermediaries are electronic, and trading and settlement can take place swiftly and easily between intermediaries, who are members of the relevant exchange.6 Immobilisation is the technique that was used in the US to deal with the problem, and is largely used for Eurobond issues.

Another technique was to dematerialise securities, so that the root of title is no longer either a piece of paper or the company’s register, but an electronic entry on the books of a central operator.7 Dematerialisation enables fast electronic settlement to take place, and thus removes many of the disadvantages of the paper-based system. It does, however, require legislation to put it in place, and in some jurisdictions and contexts systems based on immobilisation developed before any such legislation was considered.8 Dematerialised securities can, though, be held through intermediaries: this could be compulsory9 or optional, as is the position in the UK, where investors can be direct members of CREST10 or can hold through an intermediary which is a member of CREST.

The systems of holding described above can be view in diagrammatic form by the following two, very simplified, diagrams:

Figure 1.111

Even where an investor has a choice of whether to hold its securities directly or through an intermediary, the latter has many attractions. The first is the ease of trading and settlement referred to earlier. This is made even easier by the system of pooled accounts, which is described below, and the ability of intermediaries to settle trades on a net basis.12 Secondly, intermediaries can perform other functions for clients, such as record keeping, investment management services and the provision of finance. Thirdly, a portfolio of international securities held with one intermediary may, if the conflict of law rules allow this, be governed by one single law, that of the intermediary.13

II. The Risks of Intermediation

A. The Risks in General

The collection of papers in this book consider the various problems and issues thrown up by intermediated holding of securities, and the various attempts to deal with these at a national and international level. The main question which arises in relation to the holding of securities through intermediaries is whether the method of holding increases risk to the investor. The holding of securities, even directly, is inherently a risky business. The value of shares may go down as well as up depending on the fortunes of the issuer, while the value of debt securities is directly affected by the ability of the issuer to repay. These risks, known as ‘issuer risk’ are well accepted. By adding intermediation, however, the investor also incurs ‘intermediary risk,’14 which includes the risk of the intermediary’s financial failure and the risk that the intermediary will ‘lose’ the securities.15 Further, there is a danger that the holder will lose out on benefits that it had as a direct holder, such as the right to have a say in the running of the company (if the securities are shares) or to direct a bond trustee in relation to the enforcement of the bond (if debt securities). One way of assessing the system is to consider how far the position of an investor who holds intermediated securities differs from that of a direct holder in relation to all these matters.

In countries where intermediation is the only realistic way of holding securities, then this assessment would consist of trying to work out whether the system was as close as possible to direct holdings in terms of investor protection, and whether any disadvantages were outweighed by the advantages of intermediation. In countries (such as the UK) where investors have a genuine choice between holding through an intermediary and a form of direct holding through CREST,16 the assessment is rather different. There is still a strong case for reducing risk, particularly if this leads to systemic risk, if investors do in fact choose intermediation. However, the assessment is also one which needs to be done (in theory) by each investor and so there is much to be said for pointing out the advantages and disadvantages of intermediation so that an informed choice can be made.

B. The Risk of Legal Uncertainty: Conflict of Laws Solutions

There is one further risk which comes from intermediation, although it is present to some extent even where securities are held directly, and this is the risk of legal uncertainty. This can come from the lack of a developed domestic law to deal with intermediation, or, where there is cross-border trading, which is very common, from the incompatibility of the laws of different countries or the uncertainty as to which rules apply. An attempt was made to minimise this latter risk by the drafting of the Hague Convention on the Law Applicable to Certain Rights in Respect of Securities Held with an Intermediary (‘the Hague Securities Convention’)17 which attempted to formulate consistent conflict of law rules. The choice of law rules contained in the Hague Securities Convention are discussed by Maisie Ooi in chapter nine of this volume. Professor Ooi also discusses the PRIMA rule applicable under Article 9(2) of the EU Finality Directive18 and Article 9 of the EU Financial Collateral Directive19 (the ‘EU choice of law rule’). The latter rule is in any event limited to Europe, and also to certain types of transactions.20 The importance of clear and certain conflict of law rules is undeniable (Professor Ooi makes the point that this will be the case even if the International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (UNIDROIT) Convention on Substantive Rules for Intermediated Securities21 is adopted by all countries) but it is also clear that there is as yet no consensus as to what those rules should be.

The Hague Securities Convention’s basic choice of law rule is that the choice of law by the parties to the intermediary agreement will be upheld. Professor Ooi criticises this approach as lacking transparency to third parties,22 a criticism echoed by Ben McFarlane and Robert Stevens in chapter two of this volume in relation to the determination of priority issues.23 The EU choice of law rule is based on the law of the place of the account with the intermediary. Professor Ooi identifies the link between the intermediary and the account holder as the common factor in both choice of law rules, and criticises this as reflecting a particular view of the substantive law, namely that there is a separate interest at each level of intermediary.24 Guy Morton, who commented on Professor Ooi’s paper at the Conference, disagreed with this on the basis that, in formulating both choice of law rules, great care was taken to achieve neutrality between substantive law approaches, and this was critical to the success of any internationally accepted choice of law rule.

Professor Ooi suggests two alternative approaches in her paper, both of which were designed to provide the answer of a single law to choice of law questions. Both of her approaches were criticised by Mr Morton at the Conference, who strongly supported the Hague Securities Convention choice of law rule. This rule is also supported by Ben McFarlane and Robert Stevens in their chapter.25 However, in relation to priority issues, they suggest different rules,26 and in discussion Professor Stevens stated that in his view the correct approach was for there to be different conflict of law rules for different issues, and that a ‘one size fits all’ approach was wrong.

Although there is considerable merit in this view, it does mean that conflicts of law rules in relation to intermediated securities can never be simple. This is made even clearer by Gabriel Moss in chapter three, where he considers the example of securities held through a clearing house in China.27 He points out that the uncertainty of choice of law rules, as well as uncertainty as to substantive law rules, not only increases legal risk, but also leads to practical problems such as delay for investors in achieving any result at all when an intermediary is insolvent.28 The discussion in the chapters in this volume and at the Conference, make it clear that the content of choice of law rules is a matter of considerable debate, which means that there is a strong argument for at least some degree of harmonisation of substantive law.

C. The Risk of Legal Uncertainty: Substantive Law Solutions

The Geneva Securities Convention is an attempt to tackle both the possible lack of domestic certainty and the cross-border uncertainty, by drawing up substantive rules rather than conflict of law rules. It was clear from the outset of the UNIDROIT project that it would be impossible to draw up a complete set of rules which could be transplanted into every jurisdiction and achieve complete unanimity. This was partly because of the inherent difficulty of harmonisation in any area of law: any harmonised unified law would have to dovetail into the rest of the law in any given country, and the laws of various countries are generally too fundamentally different for this to happen successfully. More specifically, many countries already have their own laws on intermediated securities, and any harmonised law would have to take account of the various different systems operating. For example, some countries have direct systems, where the investors have rights against the intermediary immediately above them and also against the issuer29 while others have indirect systems, where the investors only have rights against the intermediary immediately above them.30 There is another distinction, not co-extensive with the last, between transparent systems, where all transfers are entered on a central register31 and non-transparent systems, where the transfers merely take place in the books of the lowest-tier intermediary.32 There are also matching systems, non-transparent systems where a credit to a secu...