![]()

1

Family Law and Family Justice

Key Questions

What is family law?

What is the family justice system, and how do courts and lawyers work to implement family law?

Why is it important to see family law as a matter of justice?

Family law is important. It facilitates adjustments to people’s family relationships, it protects vulnerable adults and children within families, and it supports families and their familial roles in society.1 The family justice system administers these functions as a forum for enforcing people’s rights; protecting them from harassment, bullying and abuse of power within families; and promoting values like welfare, fairness, equality and justice. These things are of fundamental importance.

Probably no country’s family law or its administration of family justice are perfect. Certainly few people in any country would suggest that the detail of family law or of the family justice system could not be improved, and much of this book presents ideas about ways in which the law could (or occasionally should) be changed. However, before getting to detailed discussion about the law, it is first necessary to understand why there should be something called ‘family law’ and a family justice system in which family disputes are resolved at all.

In the first part of this chapter, a basic overview of the world of family law and of the family justice system is offered, so that the arena for the ideas and debates in this book can be clearly delineated. In the second section, we look at some of the arguments which might be presented ‘against’ family law. These arguments give the opportunity, in the third section, to ask some fundamental questions about the nature and purpose of family law, and to make the argument ‘for’ family law.

THE WORLD OF FAMILY LAW

The first question to ask is simply this: what is family law about?

There are two basic ways in which this question could be answered. The first is a descriptive answer, which will be given in this section. The second answer is a more adventurous philosophical one, which we come to in the final part of this chapter. However, even the descriptive answer offers enough challenges for now.

A number of ideas can be offered about the core theme of family law. Jonathan Herring suggests that family law is ‘the law governing the relationships between children and parents, and between adults in close emotional relationships’, though he also notes that there are somewhat arbitrary ‘conventions’ about which sub-issues within those categories are usually thought of as the domain of family law.2 As Alison Diduck and Felicity Kaganas explain, these conventions continue to focus on ‘the monogamous sexual relationship (either actually or symbolically) between a man and a woman’.3 Elsewhere, Diduck describes family law as ‘the body of law that defines and regulates the family, family relationships and family responsibilities’.4

In general, the following basic issues are usually seen to be within the remit of family law (though some also appear in other areas of the law, such as criminal law and property law):

- The regulation of intimate adult relationships: traditionally, this includes the formation and dissolution of formal relationships (primarily marriage), together with related issues affecting non-formal relationships,5 as well as some discussion of the regulation of on-going relationships (such as protection from domestic violence).

- The regulation of family finances and property: the focus here is usually on property and financial arrangements in the event of relationship break down, but there is also discussion of finances and property within families and, occasionally, between generations.

- The regulation of parents and children: four primary issues come in here – the law’s regulation of who is a parent; children’s rights; disputes between parents about their children’s upbringing; and the protection of children from abuse and neglect by their parents.

These ‘core issues’ are supplemented in some books by discussion of connected topics, such as the law relating to older people,6 child support and state welfare provisions,7 or the legal consequences of death in families.8 However, some issues which affect families – sometimes in profound ways – are rarely considered to be part of family law: examples include immigration law9 and the parts of employment law concerning families.10

It is difficult to think of family law in isolation. Not only does it interrelate with many other areas of the law,11 but also with other academic disciplines,12 and with social policy more broadly. Social policy is about the ways in which societies are organised, about the relationship between the individual, the state, and other social actors (like religious organisations, charities, unions – in the UK coalition government’s terminology, the big society). Social policy can be broken down into subsections which focus on particular aspects of that organisation. So, for example, education policy is about the provision of schooling and other education, and normally focuses on the state’s involvement with, and role in the organisation of, nurseries, schools, colleges and universities.

Family policy is about the organisation and regulation of social functions which either are or could be performed by families in our communities. While there are some issues which are purely about families, many issues of family policy interact with other parts of social policy. For example, if the state provides nurseries for children aged 3 to 5 as part of its education policy, that impacts on how families with young children are able to organise themselves.13

Not all parts of family policy are of direct relevance to family law. Family law is only one way in which a state’s family policies are articulated, and in particular ‘family law [is] the family policy most concerned with family formation, structure and dissolution’.14 When looking at questions of family law, though, it is worth thinking about how those questions relate to broader issues of family policy. For example, when thinking about children’s residence arrangements after parental separation, the viability of shared residence arrangements is not a purely legal question. There are broader issues. One issue would be to ask about the research evidence (psychological, sociological, socio-legal) about how children react to splitting their time between two homes.15 Another is about the ability of the family to provide two physical homes for their children – and if the family’s resources cannot manage this, whether the state ought to assist them by providing housing.16 These are not all legal questions, but they are important issues for family lawyers to consider, because family law cannot be detached from its social and policy contexts.

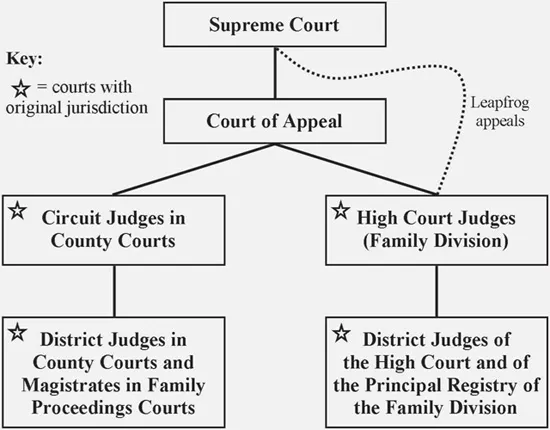

If that is the core substance of family law, what about the structures within which it is implemented? In terms of the courts, the system in England and Wales is far from straightforward.17 Family cases can start in front of any of four different levels of judge in several different courts,18 depending primarily on the complexity of the issues.19 The simplest cases are heard by district judges or magistrates sitting in Family Proceedings Courts, while the most complex cases usually start before a High Court judge.20 In between are circuit judges and district judges sitting in the County Courts, as well as district judges of the High Court and district judges of the Principal Registry of the Family Division.

Circuit judges also hear appeals from the Family Proceedings Courts and from district judges in the County Courts, while High Court judges hear appeals from district judges of the High Court and from the Principal Registry. Decisions of High Court judges and of circuit judges (whether at first instance or on appeal) can be appealed to the Court of Appeal, and Court of Appeal decisions can, in turn, be appealed to the Supreme Court. (High Court cases can also ‘leapfrog’ straight to the Supreme Court in limited circumstances.21) This less-than-obvious structure is illustrated in Box 1.1.

Box 1.1: Simplified illustration of the structure of the family courts in England and Wales, showing courts with original jurisdiction and the normal routes of appeal

However, as well as understanding the structure of the courts, it is important to appreciate the role that the courts play in family cases. While the image of a court is of a place where opposing litigants fight while a judge referees the battle and then decides the outcome, very few family disputes are like that. For example, research into the work of divorce lawyers shows clearly that courts play a small part of the overall divorce process, and that getting a final decision from a judge (rather than simply directions about how to proceed) is very rare.22 Some cases are resolved entirely independently by the parties, and some are resolved following mediation or counselling. Most, though, are settled with the assistance of solicitors, sometimes aided by barristers, but with relatively little interaction with the court. Research in the late 1990s showed that many cases went to court briefly to get guidance (known as ‘directions’) from a judge, but ‘results might be better defined as . . . agreement or compromise between the parties following some guidance from the court rather than any formal adjudication’.23 As this research highlighted, the family court ‘provides a framework within which compromises can be made’.24

The key players in most family cases are therefore the lawyers. While there is some overlap, the role of solicitors and barristers in family law work varies. Both have been studied by Mavis Maclean and John Eekelaar, who explain that the aim of both halves of the profession is to minimise conflict and work towards a fair, sustainable settlement which is ‘the best deal for their clients within the normative standards of the law’.25 In other words, the law provides the background against which lawyers help their clients to reach agreements, with the lawyers’ experience of judicial decision-making used to cross-check and guide their advice.

Solicitors do the bulk of the work in family cases, and normally see a client’s case through from beginning to end. The work involved is well explained by Eekelaar, Maclean and Beinart, whose references to ‘lawyers’ in the extract in Box 1.2 mean solicitors specifically.

Box 1.2: extract from J Eekelaar, M Maclean and S Beinart, Family Lawyers: The Divorce Work of Solicitors (Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2000) 184

Of course lawyers bargained, and sometimes put pressure on the other side, but that does not amount to ‘scoring points and settling wrongs, real or imagined’. . . . We have shown abundantly that the lawyer’s role is not confined to merely giving legal advice. It extends to providing reassurance and practical support for many clients during a particularly stressful period. It often extends to dealing with third parties. . . . [L]awyers standardly encouraged clients to discuss matters between themselves, especially those concerning children and the household contents, although they did tend to warn clients against entering into agreements with the other...