![]()

PART I

THE GENEALOGY OF HUMAN RIGHTS

![]()

1

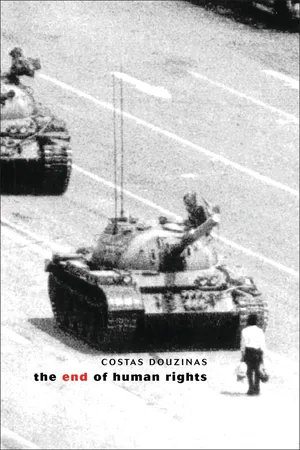

The Triumph of Human Rights

A new ideal has triumphed on the world stage: human rights. It unites left and right, the pulpit and the state, the minister and the rebel, the developing world and the liberals of Hampstead and Manhattan. Human rights have become the principle of liberation from oppression and domination, the rallying cry of the homeless and the dispossessed, the political programme of revolutionaries and dissidents. But their appeal is not confined to the wretched of the earth. Alternative lifestyles, greedy consumers of goods and culture, the pleasure-seekers and playboys of the Western world, the owner of Harrods, the former managing director of Guinness Plc as well as the former King of Greece have all glossed their claims in the language of human rights.1 Human rights are the fate of postmodernity, the energy of our societies, the fulfilment of the Enlightenment promise of emancipation and self-realisation. We have been blessed – or condemned – to fight the twilight battles of the millennium of Western dominance and the opening skirmishes of the new period under the dual banners of humanity and right. Human rights are trumpeted as the noblest creation of our philosophy and jurisprudence and as the best proof of the universal aspirations of our modernity, which had to await our postmodern global culture for its justly deserved acknowledgement.

Human rights were initially linked with specific class interests and were the ideological and political weapons in the fight of the rising bourgeoisie against despotic political power and static social organisation. But their ontological presuppositions, the principles of human equality and freedom, and their political corollary, the claim that political power must be subjected to the demands of reason and law, have now become part of the staple ideology of most contemporary regimes and their partiality has been transcended. The collapse of communism and the elimination of apartheid marked the end of the last two world movements which challenged liberal democracy. Human rights have won the ideological battles of modernity. Their universal application and full triumph appears to be a matter of time and of adjustment between the spirit of the age and a few recalcitrant regimes. Its victory is none other that the completion of the promise of the Enlightenment, of emancipation through reason. Human rights are the ideology after the end, the defeat of ideologies, or to adopt a voguish term the ideology at the “end of history”.

And yet many doubts persist.2 The record of human rights violations since their ringing declarations at the end of the eighteenth century is quite appalling. “It is an undeniable fact” writes Gabriel Marcel “that human life has never been as universally treated as a vile and perishable commodity as during our own era”.3 If the twentieth century is the epoch of human rights, their triumph is, to say the least, something of a paradox. Our age has witnessed more violations of their principles than any of the previous and less “enlightened” epochs. The twentieth century is the century of massacre, genocide, ethnic cleansing, the age of the Holocaust. At no point in human history has there been a greater gap between the poor and the rich in the Western world and between the north and the south globally. “No degree of progress allows one to ignore that never before in absolute figures, have so many men, women, and children been subjugated, starved, or exterminated on earth”.4 No wonder then why the grandiose statements of concern by governments and international organisations are often treated with popular derision and scepticism. But should our experience of the huge gap between the theory and practice of human rights make us doubt their principle and question the promise of emancipation through reason and law when it seems to be close to its final victory?

Two preliminary points are in order. The first concerns the concept of critique. Critique today usually takes the form of the “critique of ideology”, of an external attack on the provenance, premises or internal coherence of its target. But its original Kantian aim was to explore the philosophical presuppositions, the necessary and sufficient “conditions of existence” of a particular discourse or practice. This is the type of critique this book aims to exercise first before turning to the critique of ideology or criticism of human rights. What historical trajectory links classical natural law with human rights? Which historical circumstances led to the emergence of natural and later human rights? What are the philosophical premises of the discourse of rights? What is today the nature, function and action of human rights, according to liberalism and its many philosophical critics? Are human rights a form of politics? Are they the postmodern answer to the exhaustion of the grand theories and grandiose political utopias of modernity? Our aim is not to deny the predominantly liberal provenance and the many achievements of the tradition of rights. Whatever the reservations of communitarians, feminists or cultural relativists, rights have become a major component of our philosophical landscape, of our political environment and our imaginary aspirations and their significance cannot be easily dismissed. But while political liberalism was the progenitor of rights, its philosophy has been less successful in explaining their nature. The liberal jurisprudence of rights has been extremely voluminous but little has been added to the canonical texts of Hobbes and Kant. Despite the political triumph of rights, its jurisprudence has disappointedly veered between the celebratory and legitimatory and the repetitive and banal.

Take the problem of human nature and of the subject, a central concern of this book, which could also be described as a long essay on the (legal) subject. The human nature assumed by liberal philosophy is pre-moral. According to Immanuel Kant, the transcendental self, the precondition of action and ground of meaning and value, is a creature of absolute moral duty and lacks any earthly attributes. The assumption of the autonomous and self-disciplining subject is shared by moral philosophy and jurisprudence, but has been turned in neo-Kantianism, from a transcendental presupposition into a heuristic device (Rawls) or a constructive assumption that appears to offer the best description of legal practice (Dworkin). As a result, we are left with “the notion of the human subject as a sovereign agent of choice, a creature whose ends are chosen rather then given, who comes by his aims and purposes by acts of will, as opposed, say, to acts of cognition”.5 This atomocentric approach may offer a premium to liberal politics and law but it is cognitively limited and morally impoverished. Our strategy differs. We will examine from liberal and non-liberal perspectives the main building blocks of the concept of human rights: the human, the subject, the legal person, freedom and right among others. Burke, Hegel, Marx, Heidegger, Sartre, psychoanalytical, deconstructive, semiotic and ethical approaches will be used, first, to deepen our understanding of rights and then to criticise aspects of their operation. No grand synthesis can arise from such a cornucopia of philosophical thought and not much common ground exists between Hegel and Heidegger or Sartre and Lacan. And yet despite the absence of a final and definitive theory of rights a number of common themes emerge, one of which is precisely that there can be no general theory of human rights. The hope is that by following the philosophical critics of liberalism, Kant’s original definition of “critique” can be revived and our understanding of human rights rescued from the boredom of analytical common-sense and its evacuation of political vision and moral purpose. This is a textbook for the critical mind and the fiery heart.

Human rights can be examined from two related but relatively distinct main perspectives, a subjective and an institutional. First, they help constitute the (legal) subject as both free and subjected to law. But human rights are also a powerful discourse and practice in domestic and international law. Our approach is predominantly theoretical but it will often be complemented by historical narrative and political and legal commentaries on the contemporary record of human rights. To be sure, criticisms based on the widespread violations of human rights are not easily reconcilable with philosophical critique. Philosophy explores the essence or the meaning of a theme or concept, it constructs indissoluble distinctions and seeks solid grounds,6 while empirical evidence is soiled with the impurities of contingency, the peculiarities of context and the idiosyncrasies of the observer. On the other, empiricist, hand, human rights were from their inception the political experience of freedom, the expression of the battle to free individuals from external constraint and allow their self-realisation. In this sense, they do not depend on abstract concepts and grounds. For continental philosophy, freedom is, as Marx memorably put it, the “insight into necessity”; for Anglo-American civil libertarians, freedom is resistance against necessity. The theory of civil liberties has moved happily along a limited spectrum ranging from optimistic rationalism to unthinking empiricism. It may be, that the “posthistorical” character of human rights should be sought in this paradox of the triumph of their spirit which has been drowned in universal disbelief about their practice.

But, secondly, have we arrived at the end of history?7 Over two centuries ago, Kant’s Critiques, the early manifestos of the Enlightenment, launched philosophical modernity through reason’s investigation of its own operation. From that point, Western self-understanding has been dominated by the idea of historical progress through reason. Emancipation means for the moderns the progressive abandonment of myth and prejudice in all areas of life and their replacement by reason. In terms of political organisation, liberation means the subjection of power to the reason of law. Kant’s schema was excessively metaphysical and laboriously avoided direct confrontation with the “pathological” empirical reality or with active politics. But Hegel’s announcement that the rational and the real coincide identified reason with world history and established a strong link between philosophy, history and politics. Hegel himself vacillated between his early belief that Napoleon personified the world spirit on horseback and his later identification of the end of history in the Prussian State. And while the Hegelian system remained fiercely metaphysical, it was used, most notably by Marx, to establish a (dialectical) link between concepts and abstract determinations and events in the world with the purpose of not just interpreting but changing it.

Hegelianism can easily mutate into a kind of intellectual journalism: the philosophical equivalent of a broadsheet column in which the requirements of reason are declared either to have been fulfilled historically (as in right-wing Hegelians and more recently the musings of Fukuyama) or to be still missing (as in messianic versions of Marxism). In both, the conflict between reason and myth, the two opposing principles of the Enlightenment, will come to an end when human rights, the principle of reason, becomes the realised myth of postmodern societies. Myths of course belong to particular communities, traditions and histories; their operation validates through repetition and memory, a genealogical principle of legitimation and the narrative of belonging. Reason and human rights, on the other hand, are universal, they are supposed to transcend geographical and historical differences. If myth gets its legitimatory potential from stories of origin, reason’s legitimation is found in the promise of progress expounded in philosophies of history. A forward direction is detected in history which inexorably leads to human emancipation. If myth looks to beginnings, the narrative of reason and human rights looks to teloi and ends.

In postmodernity, the idea of history as a single unified process which moves towards the aim of human liberation is no longer credible,8 and the discourse of rights has lost its earlier coherence and universalism.9 The widespread popular cynicism about the claims of governments and international organisations about human rights was shared by some of the greatest political and legal philosophers of the twentieth century. Nietzsche’s melancholic diagnosis that we have entered the twilight of reason, Adorno and Horkheimer’s despair in the Dialectics of the Enlightenment10 and Foucault’s statement that modern “man” was a mere drawing on the sands of the ocean of history about to be swept away, appear more realistic than Fukuyama’s triumphalism. The Frankfurt sages argued that the conflict between logos and mythos could not lead to the promised land of freedom, because instrumental reason, one facet of the reason of modernity, had turned into its destructive myth. The dialectic no longer represents the voyage of homecoming of the spirit. Reason’s inexorable march and its attempt to pacify the three modern forms of conflict, conflict within self, conflict with others and conflict with nature, led to psychological manipulation and the Gulags, to political totalitarianism and Auschwitz, finally to the nuclear bomb and ecological catastrophe. As a new tragedy unfolds daily in east and west, in Kosovo and East Timor, in Turkey and Iraq, it looks as if mourning more than celebrations becomes the end of the millennium.

Unfortunately political philosophy has abandoned its classical vocation of exploring the theory and history of the good society and has gradually deteriorated into behavioural political science and the doctrinaire jurisprudence of rights. On the side of practice, it is arguable that Home Secretaries should come from the ranks of exprisoners or refugees, Social Security Secretaries should have some experience of homelessness and life on the dole, and that Finance Ministers should have suffered the infamy of bankruptcy. Despite the consistent privileging of experience over theory, this is unlikely to happen. Official thinking and action on human rights has been entrusted in the hands of triumphalist column writers, bored diplomats and rich international lawyers in New York and Geneva, people whose experience of human rights violations is confined to being served a bad bottle of wine. In the process, human rights have been turned from a discourse of rebellion and dissent into that of state legitimacy.

At this time of uncertainty and confusion between triumph and disaster, we should take stock of the tradition of human rights. But can we doubt the principle of human rights and question the promise of emancipation of humanity through reason and law, when it seems to be close to its final victory? It should be added immediately that the claim that power relations can be translated fully in the language of law and rights was never fully credible and is now more threadbare than ever. We are always caught in relations of force and answer to the demands of power which, as Foucault argued forcefully, are both carried out and disguised in legal forms. Recent military conflicts and financial upheavals have shown that relations of force and political, class and national struggles have acquired an even more pervasive importance in our globalised world, while democracy and the rule of law are increasingly used to ensure that economic and technological forces are subjected to no other end from that of their continuous expansion. Indeed, one of the reasons that gives normative jurisprudence the unreality, about which law students so often complain, is its total neglect of the role of law in sustaining relations of power and its descent into uninteresting exegesis and apologia for legal technique.

At the time of their birth, human rights, following the radical tradition of natural law, were a transcendent ground of critique against the oppressive and commonsensical. In the 1980s too, in Poland, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Romania, Russia and elsewhere, the term “human rights” acquired again, for a brief moment, the tonality of dissent, rebellion and reform associated with Thomas Paine, the French revolutionaries, the reform and early socialist movements. Soon, however, the popular re-definition of human rights was blanked out by diplomats, politicians and international lawyers meeting in Vienna, Beijing and other human rights jamborees to reclaim the discourse from the streets for treaties, conventions and experts. The energy released through the collapse of communism was bottled up again by the new governments and the new mafias in the East which look the same as the ...