![]() Part 1

Part 1

Making sounds![]()

1 Silence

War is diplomacy carried on by other means.

Von Clauswitz

Silence is argument carried on by other means.

Che Guevara

To understand sound we must know silence. To hear sound fully we must hear silence.

An easy aphorism to write, but silence is a difficult thing for most of us to experience these days. What passes for silence in our lives is an ongoing stew of hums, whirrs, intermittent buzzes, and occasional roars from the machines that populate our world; squeals of car tires, the blare of car horns, TVs and radios left on in an endless ambient drone as a weird substitute for the enfolding presence of human conversation, the endless fuzzy sigh of air-conditioning units spreading dehumidified air (and mold, and spores, and germs) throughout offices and homes. For many people born into industrialized societies since the early nineteenth century, silence is – well – almost unheard of.

In the last fifty or so years, the escalation of background sound has been matched by the decibel overload of foreground sound. Dire reports are published all the time about the widespread hearing impairment (particularly loss of high frequency overtones) in young people because of the excessive loudness (measured in decibels) of the sounds to which the ears are exposed; personal stereos with headphones are frequently cited as the worst culprit, but only one among many.

Contrast this trend with the writings of anthropologists who study indigenous peoples in the jungles of Amazonia or Indonesia. They report that among hunter-gatherer cultures it is still common for people to be able to hear and interpret extremely faint sounds: the rustle of animals moving through the fallen leaves on the forest floor a half-mile away, the flutter of bird wings that tell both distance and direction of flight, the change in insect sounds that warn of a change in weather several hours hence. While some observers of these skills are apt to ascribe them to some sort of extra-sensory power, it seems clear that nothing these people are doing requires any power beyond an unimpaired hearing ability combined with the skill of attentiveness and the experience to interpret very small sound differences.

These abilities are not beyond us, even if we have spent many hours connected to our iPods. But we have some work to do. Over the years we progressively hold more and more tension in our skeletal muscles – the muscles we consciously use to move our internal structure of bone and cartilage around. We do so as an unconscious way of bracing against the shock of a loud – or just a new – sound. These held or “residual” muscle tensions desensitize us, so that eventually we no longer even seem to hear the annoying ambiences that accompany us throughout the day.

It’s a perfectly legitimate way of coping with contemporary life, and to some degree we all do it. But we pay a price. We are armoring ourselves against the rest of the world. Specifically, we are no longer fully available to the world of sound around us; we are less likely to really pay attention to other people speaking to us unless they are speaking loudly, or even better, are speaking loudly on television or radio or podcast.

People who enjoy classical music but are used to hearing it on the speakers or headphones of the home-entertainment centers in their living rooms often express disappointment when they actually go to a concert; the orchestra just doesn’t sound as brilliant and powerful as it does on the CD at home. People who go to films a lot often complain about difficulties in understanding the actors when they attend a live theatre performance even when the actors are speaking at a reasonable volume with full clarity of articulation. Unfortunately such complaints often lead to decisions by theatre managements to put body microphones on the actors to amplify their voices, or to engage in general “sound enhancement,” so that the human voice now reaches the audience’s ears from loudspeakers in a general wash rather than in specific, subtle, direct communication from the individual actors’ bodies. I believe I am not too far wrong when I speculate that a growing number of audience members at live theatre events are becoming willing to sacrifice much of what makes live theatre a unique art form in order to recreate the feeling that they are really sitting in a movie theatre being bathed in the pumped-up surround sound: the Multiplex Experience.

So the ability to let go of residual tension in the skeletal muscles becomes crucial in finding our way back into a fully sensitized, available body; a body that can listen. I have to emphasize that the process of becoming sensitized, or available to stimuli, or “finding neutral”, in no way means that as actors or people we are becoming passive or non-analytical. On the contrary, our sensory availability simply gives us more data to evaluate. Famed director Peter Brook puts it eloquently in describing this state of vibrant, alert awareness within which to find an equally vital form of silence:

In the search for the indefinable, the first condition is silence, silence as the equal opposite of activity, silence that neither opposes action nor rejects it. In the Sahara one day, I climbed over a dune to descend into a deep bowl of sand. Sitting at the bottom I encountered for the first time absolute silence, stillness that is indivisible. For there are two silences: a silence can be no more than the absence of noise, it can be inert, or at the other end of the scale, there is a nothingness that is infinitely alive, and every cell in the body can be penetrated and vivified by this second silence’s activity. The body then knows the difference between two relaxations – the soft floppiness of a body weary of stress telling itself to relax, and the relaxation of an alert body when tensions have been swept away by the intensity of being. The two silences, enclosed within an even greater silence, are poles apart.

Threads of Time, pp. 106–7

The listener is fully open to the silence, and the energy of listening comes from the attentiveness of every cell of the body. But there would seem to be another crucial element. The vitality of the stillness that Brook perceives in the empty desert proceeds at least in part from the space which is always fully open to the potential for sound, an environment which expands the presence of the listener by continuously encouraging a greater and greater attentiveness. So there is a profound difference between the living silence that Peter Brook found in the vastness of the Sahara Desert and the silence that one might encounter in an anechoic chamber – a chamber in which all walls, the floor, and the ceiling are completely damped acoustically, so that no sound waves can reflect. Sounds produced in anechoic chambers are useful to acoustic engineers who wish to study only those frequencies emanating from a sound source without the complication of reflected sound from the environment. But the sound that a human voice produces in an anechoic chamber is a voice crying in a void, pure but strangely inhuman. The silence that envelops one in such a place is the silence of the dead.

In a silence alive with the potential for sound, our awareness continues to expand and our acuity of perception increases. Emerging from this attuned awareness of silence, even the tiniest sound can have texture, imagistic power, and can evoke the entire world within which the sound lives.

This is some of what Catherine Fitzmaurice, noted voice teacher and a trained and acute listener, heard during a stay in Moscow and Petersburg:

Some sounds heard in Russia

Fricatives, deep-throat vowels; militia sirens; laboring buses; horses’ hooves at night; endless traffic; endless talk in four-hour Tolstoy dramas; long applauses becoming unison clapping; in his house, Scriabin recorded, playing his own piano compositions; beggar children asking, asking; loudspeakers in public places; pressed voices singing folk songs with a little yelp at the end of the phrase; a young woman on her cell phone giggling during a performance of Giselle at the Bolshoi Ballet; more Scriabin in the Moscow Conservatory great hall; high heels clipping on uneven pavements; a youth pissing in a bottle and laughing in the back row during a theatre performance in English; gun shots at two in the morning; someone (unanswered) banging on the door to my apartment at two in the morning; the phone (unanswered) ringing at two in the morning; metal whining during a high-speed train trip back from St. Petersburg; the urgent clatter of feet on the marble floors of the Moscow metro; loud passionate arguments between big men with love in their voices and ending with three noisy kisses, shoulder slaps, and a grunting bear hug.

If we can listen out of an alive, sensitized personal silence, there is a lot in the world worth hearing. If we then can feel our own sounds moving through our bodies with the same alert availability, we can feel subtle changes in vocal sound and action. This is where our journey from silence into vocal sound – the assertion of our humanity – needs to begin.

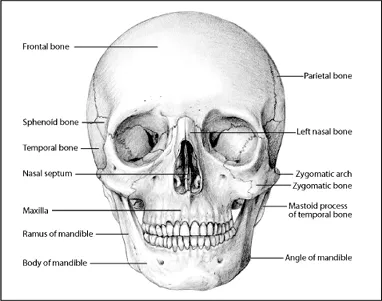

Figure 2. The human skull, front view.

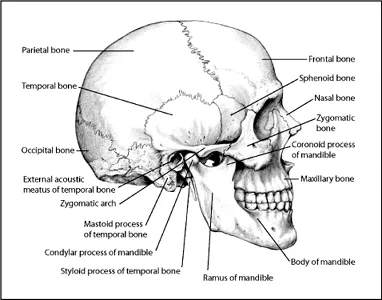

Figure 3. The human skull, lateral view.

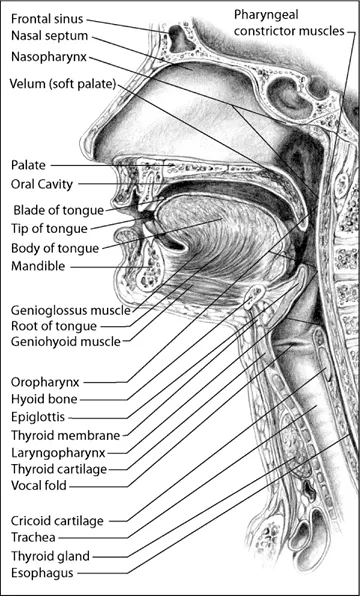

Figure 4. The vocal tract: median section.

![]()

2 The space that shapes sound

On page 9 is a lateral – or side – view of a human head, seen as though the head were cut in half. (Not exactly into two equal halves, though; if it were cut exactly in half, it would be called a sagittal section.) This view allows us to see the structure that we call the vocal tract, the space that shapes sound. The voc...