![]()

![]()

This chapter will introduce you to some of the key concepts surrounding the subject of posture in terms of assessment and re-education. It aims to provide practitioners of manual therapy, exercise and movement specialists, patients, exercisers, and anyone interested in human movement, with a number of useful and effective tools that will improve postural control, both structurally and functionally. Hopefully, this book will not overcomplicate the process of assessment and re-education – not all the information here will be necessary for your needs. It has, however, been put together in such a way that you can develop your own re-education programmes based on a firm foundation of classical and contemporary schools of thought.

Defining posture

It is difficult to define posture as it is interpreted differently by different people. The military officer, the teenager, the model, the dancer, the personal trainer, the actor, the anthropologist, the martial artist, the sculptor – these people and many more will all have their own ideas about what posture means to them. With this in mind, it is difficult to create a postural ‘norm’, a set of standards against which posture can be measured. Were such a norm to exist, all the above people would have a common point of reference. However, over a period of time, these postures become each person’s own norm, and begin to feel so right and balanced that movement towards any other posture may feel unnatural. In this way, temporary attitudes become long-term habits as the body moulds itself into fixed patterns that can influence current and future performance and functioning.

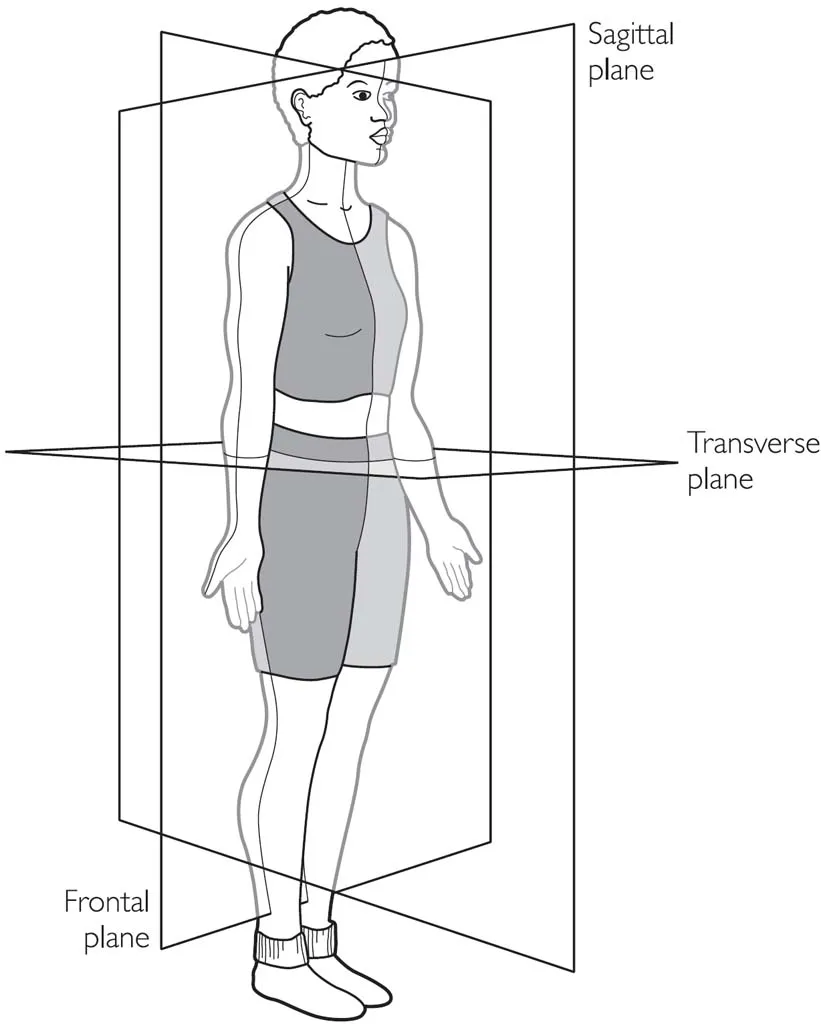

Posture is often thought of in geometrical or Cartesian terms, where an ideal posture consists simply of the stacking of one joint on top of the other in relation to three planes of motion and axes of rotation – a configuration reinforced by good muscle balance around the joints (see fig 1.1). While this is true to some extent, it fails to recognise the way in which we achieve this configuration and how we are able to maintain it during movement. To look at these points, we must delve deeper and consider posture from another point of view – efficiency of use.

Figure 1.1 The body’s planes of motion

Although there are an infinite number of possibilities in the configuration of limbs and their mechanical use for any given task, inherent in every task is a way of organising and using the body with the least wear and tear and the most efficient functioning. For example, sitting down on a chair can be performed in many ways; however, only a few of these will require the least use of energy and effort. Much of the time, we become accustomed to using excessive amounts of energy when moving; indeed, many of us exhibit unnecessary amounts of muscular tension even when sitting or standing. This raises the question not of what’s right or wrong, but rather what works? What positions or movements allow for optimal efficiency? The answers to these questions presuppose that posture is not necessarily defined by static positioning alone, but more importantly by the way we organise our bodies as we move. When such an attitude is adopted by practitioners, this type of questioning can effectively move patients towards a postural re-education programme that is motivated by a process of self-exploration and body awareness: a situation that is almost childlike in nature, and one that allows the body to re-learn and self-regulate its own posture.

The development of posture

The human body is a homeostatic organism. It is constantly adjusting, modifying and learning in response to internal and external stimuli: a process of self-regulation by continual feedback. These stimuli imprint themselves physically and mentally on the body in the way of learning – some desirable, some not so desirable. In fact, much of this learning begins before we are even born. Our ability to move begins in utero, we perform slow controlled movements, as well as rapid ones, almost as if we are stretching and strengthening in some way – a process known as pandiculation. These innate movement patterns appear to be directed by the precisely controlled and progressive expression (and inhibition) of important reflex pathways. When we are born, these patterns continue to help our learning as we lift and turn our heads, as we learn how to crawl, roll and sit, and eventually as we learn how to stand and walk. The systematic emergence of these movement patterns are important developmental milestones that can provide us with knowledge of how postural control evolved from birth. Much can be learnt from infantile movement patterns and the realisation that all children learn how to control posture in a very short space of time. This process implies a rapid learning curve, one that can be applied to adult re-education.

Further understanding of posture may require explorations into our ancestral heritage, and investigations into how and why human bipedalism has evolved and adapted over millions of years. Considering the extent of musculoskeletal dysfunction and movement impairment in today’s society, the role of posture in this process, and an appreciation of how we used to move may provide clues to the restoration of optimal posture and function.

Lastly, postural re-education strategies should, perhaps, incorporate and integrate concepts of animal behaviour, in particular, those of other primates such as the great apes. It is often forgotten that humans are primates and as such we share much of our framework and potential motor behaviour with other apes. The overall aim is subjectively to model the origin of human movement from a diverse range of study options, and use this information to design effective postural re-education programmes in adults. A number of these principles are reflected in the postural lesson plans in chapters 7–10.

Control of posture

As adults, we often take our ability to sit, stand and move for granted – that is until we lose the ability to do so effortlessly. Unless this education is continued in the same way as it started, we can easily lose the ability to organise our limbs effectively and move efficiently. We may also lose the ability to notice the very stimuli that helped us to organise ourselves in the first instance. This inherent ability is known as feedback and feed-forward, and is largely governed by our proprioceptive and exteroceptive systems, which provide postural adjustments accordingly. The proprioceptive system senses changes in body position, posture and movement via specialist receptors that feed back information to the central nervous system. The exteroceptive system senses changes in our immediate environment through the senses of vision, hearing, touch, smell and taste. The basic principles of proprioception and how these intricate mechanisms help us to control stability and balance by compensatory and anticipatory postural adjustments are discussed in chapter 2. Using this knowledge, these same mechanisms of postural control can be enhanced further through appropriate exercise and movement. In this way, the nervous system can once again learn to interact continually with the environment, so that we can organise our bodies quickly and efficiently.

Evaluating posture

Optimal posture is more efficient than any other type of posture: the proprioceptive mechanisms are beautifully integrated to bring the body into a configuration where all weight-bearing articulations are subjected to minimal compression and stress. As we attempt to ‘measure’ posture, we may initially observe such a configuration statically, through observations of joint alignment. We may also look at how these characteristics affect our ability to function dynamically, by assessing movement potential, balance and coordination.

The assessment of static posture is usually conducted against a gravity line, which provides a point of reference for observation of joint alignment. These observations can then be correlated with those of seated or lying assessments, and later confirmed with specific muscle function testing. This provides an overall picture of the way the body organises itself statically in relation to gravity, and is also known as structural efficiency. Variations away from the gravity line can be interpreted within the context of existing pain and impairment, or can be used as indicators of potential dysfunction. Some common postural variations are discussed in chapter 4.

The assessment of dynamic posture usually involves the performance of key movement patterns that challenge a number of important postural mechanisms, such as coordination, balance, economy of effort, and reversibility. This provides an overall picture of how the body organises itself in preparation for and during movement, and is also known as functional efficiency. A number of important movement assessments are explored in chapter 4, with discussions of why they are vital to postural health.

Putting this altogether, we now have a different model for posture: one that focuses on body efficiency or how the body is used for any given task. From an evaluation perspective, this doesn’t stop at observation of joint alignment. In fact, a more suitable term might be body configuration, where configuration relates to how parts of the body are arranged and interconnected, so that the body functions correctly.

A model for re-education

Many of the techniques presented in this book are synergistic in the sense that they are more effective when they are performed as a sequence, rather than when they are performed in isolation. Each movement sequence aims to meet a specific postural objective, and movements are organised in such a way to maximise learning and change. To help this learning process, a number of therapeutic practices are used in a specific way that allows accumulative change, in that each method effectively builds on the previous method in the sequence. Many of these practices are discussed in chapter 6, and include positional release and contract-relax techniques, which can then be effectively programmed alongside integration techniques, to build postural lesson plans.

The objective of each lesson plan is not to correct a particular postural dysfunction, but to allow you to focus on how you are using a particular body part in relation to other body parts. The result is two-fold:

1. Effective resolution of pain and dysfunction, as the nervous system recalibrates itself to detect postural disturbances at a finer level.

2. Increased efficiency of movement and economy of effort, as the body learns to organise itself differently in relation to itself and the environment.

Such a change in self-perception, whether the objective is to eradicate pain, or to prevent pain and maintain good health, is an important result of postural re-education. In the majority of cases, this process involves improving body awareness, an approach that is heavily reliant on effective ‘re-wiring’ of the body’s sensation of position and movement. As previously mentioned, a number of techniques can be used to achieve this, which can be self-administered or practitioner-assisted.

These techniques have been organised into 20 lesson plans, thematically organised around the achievement of common postural objec...