- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Creative Methods in Organizational Research

About this book

Written for the researcher who wants to inquire into organizational life in a creative way, this innovative book will equip readers with the tools to gather and analyze data using stories, poetry, art and theatre.

Ideas are substantiated by reference to appropriate theory and throughout the reader is encouraged to reflect critically on the approach they have chosen and to be alert to ethical issues. Revealing case studies show how the research approaches covered in the book work in practice.

Challenging readers to reassess what is possible when conducting research, Creative Methods in Organizational Research will enrich the research experiences of post graduates in the fields of organization studies, management and management education.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 3

CREATIVE DIALOGUE

OVERVIEW

- Creative dialogue as a form of collective inquiry

- Underlying principles and theory

- How to use creative dialogue in organizational research – creative dialogue for a shared organizational problem, or dialogue in a collaborative research group

- Two case studies showing creative dialogue in practice

- Working with the data

- Conclusion

- Discussion questions

- Further reading

CREATIVE DIALOGUE AS A FORM OF COLLECTIVE INQUIRY

Alan took the creative dialogue method to a compound in Lusaka, Zambia, where three key people from different aid agencies had major difficulties with each other. This was threatening the future existence of the health project, affecting up to 80,000 people. Alan took his flipchart and spent the weekend with the three leaders, working together using a dialogue procedure to explore their shared problem. At a pivotal moment, one of the trio stood up and wrote, ‘It’s me – I’m the problem’ on the flipchart. This moment of insight did not lead to a scapegoating of this one individual – on the contrary, it freed all three leaders to reinterpret their struggle, not as a battle with each other, but as the challenge of finding constructive ways of working together. The three leaders have now put forward a proposal to their agencies, which has been accepted. Alan was ecstatic – ‘It works!’ he wrote in an airmail letter from the compound.

This is not a piece of research, but it is an event that arose from the use of dialogue as a research method. A friend of Alan’s was participating in a collaborative research group using a dialogue method. She suggested to Alan that he might consider using the method to prepare for the task that he would face in his new role, where he would be involved in projects seeking to improve the lives of families hit by AIDS and HIV. Alan took up the offer, and so, on a sunny afternoon in a Devon garden, a group of friends and colleagues worked together to produce three learning maps that eventually travelled from a Devon back-garden to a shantytown compound in Zambia, where the process was successfully replicated.

By engaging in dialogue with others, Alan was able to explore his thoughts and feelings about his new role ahead of time, and to envision the inherent challenges and possibilities in ways that he had not previously considered. Our own experience had been similar when, in our collaborative research group, we experienced the power of dialogue to recreate meaning when new and shared understandings of issues and events seemed somehow to unfold from our public discussions. Dialogue creates a novel setting that changes the everyday ground-rules for interpersonal communication, and replaces these rules with prescribed roles and behaviours that determine who, when and how co-researchers will interact as storytellers, listeners and sometimes as flipchart ‘artists’. In this way, unlike many other approaches, the procedure creatively incorporates multiple methods for accessing experiential data (for example, storytelling and artwork).

By way of explaining dialogue, we can start by asking whether the reader will remember occasions when she or he was in discussions with others about something in a group – a group of friends or colleagues, a meeting, tutorial or seminar for instance – and felt really frustrated. It might be productive to try to disentangle the possible causes of this frustration. Perhaps you felt you could not get a word in edgewise. Perhaps you noticed that someone else in the group could not find their voice. You thought at times that the discussion or argument was getting nowhere. Perhaps you were unimpressed by the ways that some people in the group dominated the discussion. And, ultimately, you felt that the discussion achieved nothing. These are the kinds of everyday experiences that we have where we know that there was something not right about the processes of engagement and communication between people.

What dialogue tries to do is to get underneath the causes of this kind of typically frustrating experience. Figure 3.1, lists the kinds of behaviours that are helpful to dialogue and therefore which can help us to address why meetings sometimes can be irritating experiences. We aim to show how this can be achieved in a research context.

- Reliance on discussion, not speeches Learning by talking – involves exchange of data, reasoning, questions and conclusions

- Egalitarian participation Equality: hierarchy is a great inhibitor of collective learning

- Multiple perspectives Differences foster collective learning – there is a need for a variety of perspectives to challenge accepted practice and to hold ensuing tension whilst new learning emerges

- Non-expert-based dialogue Organizational members thinking together have the capability to generate workable answers to the organizational problems and cannot act responsibly except on the basis of their own conclusions

- Participant-generated database Participants are the primary sources of data – public discussion constructs meaning

- Creation of a shared experience Provide a shared experience of acting in new ways

- Creation of unpredictable outcomes The meaning that the collective constructs is relatively unpredictable.

Figure 3.1 Critical Elements for the Facilitation of Dialogue (Adapted from Dixon, 1997)

Dialogue enables people who are trying to work together, like colleagues and/or co-researchers, to reveal, encounter and capture the nature, origins and consequences of sense-making processes in the ‘here and now’ of human interactions in organizations. Dialogue is collective inquiry into collective thinking and meaning-making processes that generates research outcomes in the form of collective learning. Collective learning can be viewed as a participant-generated database, as co-researchers are the primary sources of data from which their public discussions construct shared meanings.

Dialogue involves deliberately bringing to the surface the underlying assumptions and mindsets that govern people’s individual and collective behaviour in social interactions. As with all of the creative research methods that are considered in this book, dialogue allows the researcher and research participants to access rich and multifaceted aspects of their lived experience in ways that may not normally be available. In this particular case, dialogue brings unconscious aspects of the participants’ thinking and decision-making processes into conscious awareness.

In dialogue, personal and collective meanings may be said to ‘vibrate’, and are shaken around to reveal new understandings and action possibilities. It enables different ‘ways of seeing’ to unfold with regard to participants’ reported experiences of, for example, their work roles, relationships, shared problems and significant events. This can be liberating for individuals and teams as they come to realize that they can change what and how they think together as a means of attaining their visions and goals. Equally, this can be threatening to those who may be used to exercising power through their ability to impose their definitions of situations on others.

We have used dialogue successfully as a collaborative procedure for researching processes of organizational learning, strategic development and organizational culture change; group and team dynamics, with particular reference to decision making and problem solving; and leadership as a distributed process of reciprocal meaning-making (Beeby et al., 2002). Dialogue can also be usefully integrated with the sense-making and action planning components of other interventionist forms of organizational inquiry such as action research and action learning. These approaches lend themselves to creative dialogue as they seek to implement organizational changes that are anchored in collaborative diagnoses of problem areas that typically involve the collection, discussion and interpretation of data as the basis for collective action.

As dialogue is a complex and elusive concept, we begin this chapter by considering alternative ways in which it has come to be defined and characterized in the literature. We then present two methods that we have used in our own research. We provide case-study examples of how we have used these methods in practice to collect, record and analyse experiential data.

UNDERLYING PRINCIPLES AND THEORY

Peter Reason (2006) has proposed that dialogue may be seen as central to action research, and as contributing to what he sees as the contemporary movement in qualitative research:

… away from validity criteria that mimic or parallel those of empiricist research toward a greater variety of validity considerations that include the practical, the political, and the moral; and away from validity as policing and legitimation toward a concern for validity as asking questions, stimulating dialogue, making us think about just what our research practices are grounded in, and thus what are the significant claims concerning quality we wish to make.

(Reason, 2006, p. 191)

The concept of dialogue came to the fore in the literature on organizational learning and knowledge management during the 1990s, as a new type of communication process that is characterized by collective thinking (Beeby and Booth, 2000). Dialogue emerged as a special kind of talk that involves more than the familiar everyday communication processes of conversation, discussion and debate (Schein, 1993; Watkins and Golembiewski, 1995; Dixon, 1998). It additionally embraces the thinking processes and patterns that underpin such transactions between people. In a seminal contribution to this field, Isaacs defines dialogue as ‘a sustained collective inquiry into the processes, assumptions and certainties that compose everyday life’ (Isaacs, 1993, p. 25) and reports its emergence as a ‘process for transforming the quality of conversation’ (Isaacs, 1993, p. 25) in group settings.

Schein states that ‘an important goal of dialogue is to enable the group to reach a higher level of consciousness and creativity through the gradual creation of a shared set of meanings and a common thinking process’ (Schein, 1993, p. 43). He argues that dialogue as ‘a basic process for building common understanding’ (Schein, 1993, p. 47) is a necessary condition for effective communication between members of different cultural subgroups, and thereby for tapping into the collective intelligence of disparate group members to enhance organizational learning.

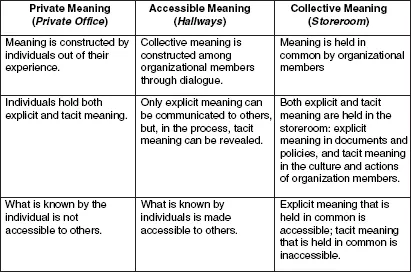

Dixon (1997) uses the metaphor of hallways to locate dialogue as the second stage of a three-stage process of organizational learning. The metaphor represents the process by which individually held tacit and explicit meanings are made accessible to others and thereby become shared, collective meaning. Dixon’s model is summarized in Figure 3.2.

In this metaphor, individuals working alone construct meaning from their experience in private offices. What is known by the individual remains private unless and until it is made accessible to others during meetings in hallways, where collective meaning is constructed by organizational members through dialogue, and then held in common by them as if in a storeroom.

Figure 3.2 Differences between Private Offices, Hallways and Storerooms (Adapted from Dixon, 1997)

Dixon (1997) identifies learning maps as one of several hallways that are currently in use in the real world of organizations. By learning maps, she means ‘graphic, wall size illustrations of an issue an organization is dealing with’, around which learning occurs via team discussions that are characterized by seven critical elements. These are elements that ‘any such process would need in order to facilitate collective meaning’ through dialogue. The elements are listed in Figure 3.2.

Much of the literature on dialogue merely assumes its validity as a research tool, and focuses instead on its use in organizational interventions. Although this is clearly a strength of the method, and as such it may be located broadly within the field of action research, it is also worth situating it within the appropriate research literature before exploring particular research methods based on dialogue.

From the research perspective, Reason and Heron’s art...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Contributors and Authors

- Introduction

- UNDERPINNINGS

- THE METHODS

- REFLECTIONS

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Creative Methods in Organizational Research by Mike Broussine, Mike Broussine,Author in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.