![]()

1

Introduction and Overview

The departure point of this book will be familiar to anyone even moderately versed in the management literature: that the world of business is becoming ever more global in scope, and consequently that large global firms (hereafter referred to as MNCs, multinational corporations) are emerging as some of the most influential and powerful institutions in the global economy, transcending and possibly even displacing nation states in their ability to drive economic development.

Such a bold statement would often be backed up with pages of analysis, explaining and justifying that business is indeed becoming more global, and making a case that somehow the rules of the game are changing in a way that demands new strategic and/or organizational responses from MNCs. But the approach here is somewhat different. While many of the changes alluded to above are clearly under way, this book has a very different story to tell, one which does not even require the world of business to be changing in fundamental ways. The story is one of internally driven changes to the strategy and structure of the multinational corporation.

The book draws on research conducted by the author and many others into the workings of large MNCs – corporations such as Ericsson, GE, BP and Nestlé, whose annual sales revenues typically exceed $20 billion and whose operations span 50 or more countries. It is concerned with understanding what the concept of strategy means for such large and geographically dispersed corporations, and how they can be structured in such a way that they can reap the benefits of size without sacrificing the benefits of local presence. This is certainly not a new research agenda – pioneers such as John Fayerweather (1969), John Stopford and Louis Wells (1972) and C.K. Prahalad (1975) addressed these issues more than twenty years ago, and there has been a steady stream of research ever since. But one common theme that is often not explicitly recognized is that all the leading studies in this area are written from the perspective of head office managers, the individuals at the corporate centre. The focus on these executives is of course of the utmost importance – they are accountable for the performance of their corporation, and they have formal authority to enforce whatever changes they deem appropriate. But if we believe some of the recent advances that portray the MNC as an interorganizational network (Ghoshal and Bartlett, 1990) or a nearly recomposable system (Hedlund, 1997), it becomes increasingly obvious that head office managers have a less firm grip on the worldwide activities of their corporation than they would like. Stories of foreign subsidiaries deliberately going against the directives of their parent company, and even severing their formal ties with the corporation, are commonplace. And the development of sophisticated socialization mechanisms – such as the use of expatriate managers and global training programmes – is frequently discussed as a means of mitigating the limitations of more traditional control mechanisms.

The unique positioning of this book, then, is its focus on the foreign-owned subsidiary as the principal unit of analysis. Certainly there have been plenty of other studies of subsidiaries over the last twenty years, but they have typically embraced the conventional line of thinking that the subsidiary ‘does what it is told’ by the parent company. The approach taken here, by contrast, is to view subsidiary managers as more or less ‘free agents’. They are employed by the multinational parent company and they take actions that they believe are in the best interests of the corporation as a whole, but that does not mean they will always act in conformance with the expressed wishes of head office managers. Such subversive behaviour may sound like a good way of cutting short a promising career, but the fact of the matter is that there is plentiful evidence that it occurs, and that it can be extremely beneficial to both subsidiary and parent. One of the intriguing dilemmas that comes out in several places in the book is the split personality that effective subsidiary managers appear to have – they are both good corporate citizens and mavericks at the same time.

But it is not just the ‘free agent’ perspective on the subsidiary manager that makes this book important. It is the observation that the actions of subsidiary managers can have widespread implications for both the structure and the strategy of the multinational corporation as a whole. The research described in the book began with a few simple accounts of maverick subsidiary managers and the initiatives they had pursued, but in following their stories, and the consequences that their actions had elsewhere, it becomes apparent that the research has important implications at the level of the corporation, as well as at the level of the subsidiary. To return to an earlier point, the MNC is much better viewed as an interorganizational network than a monolithic hierarchy, because every node in that network (that is, each subsidiary) has the potential to take actions that can influence the rest of the network. Clearly, parent company managers are still the most influential actors in the network, and the best positioned to drive strategic or structural changes in response to changes in the business environment. But one cannot ignore the fact that many of the strategic and structural changes that are observed in MNCs are internally driven, that is, initiated from below by subsidiary managers.

What sort of strategic and structural changes are we talking about? One example will be mentioned here – the tendency of large MNCs to locate more and more value-adding activities outside the home country. The traditional model, as exemplified by corporations such as Caterpillar Tractor and Matsushita, was of a strong corporate centre in which all technological development, most manufacturing and all key decision making was colocated. The emerging model – which has in reality been emerging for probably thirty years – suggests a much more geographically dispersed value chain. Xerox has R&D units in the US, Canada, the UK and France. Volvo has manufacturing in Sweden, Belgium, Holland, Canada and five Asian countries. ABB, the quintessential modern MNC, has global business units in about ten countries. All this is well known, and so much part of the contemporary business environment that researchers have shifted from questions of whether to disperse activities, to how dispersed activities can best be organized. Indeed the challenge nowadays is to find examples of MNCs that do not have dispersed value-adding activities.

But what factors caused this dispersal of value-adding activities? The conventional wisdom, and the opening paragraph of this chapter, would highlight the various facets of globalization, such as regional trade agreements, technological changes, converging consumer tastes, new international competitors and so on. The emergent species of MNC, it is argued, can be seen as an adaptive response to changes in the global business environment – if customers, competitors and suppliers are now global, the MNC itself should reflect that geographical dispersal. Previously concentrated MNCs, such as Caterpillar and Matsushita, have indeed shifted manufacturing and even some development work abroad.

Working from an internally driven change perspective, however, provides a rather different interpretation of the phenomenon of geographic dispersal. Back in 1981, Yves Doz and C.K. Prahalad observed that foreign subsidiaries, as they develop resources in their local market, gradually reduce their dependence on the parent company and gain de facto control over their own destiny. Fuji Xerox, for example, started life as a sales and marketing company, and only began doing development work because it needed copiers that could cope with the very thin paper often used in Japan. But this R&D operation, by virtue of its location in a leading-edge cluster of competitors, soon took on a life of its own and is now acknowledged by Xerox managers as more advanced in colour copying than anything in the US. The result, then, was a major R&D presence in Japan, and yet another piece of evidence that effective MNCs tend to disperse their value-adding activities around the world. But the process was facilitated through the bottom-up efforts of managers in Fuji Xerox and not through the top-down directives of parent company managers in the US.

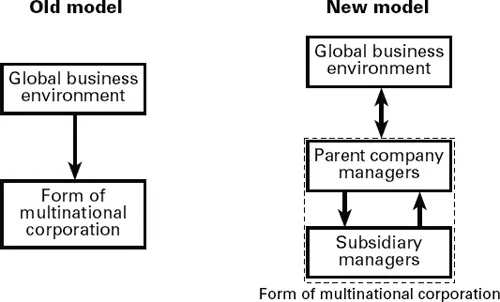

In summary then, the observed changes in MNC strategy and structure are as much internally driven as they are externally imposed. In particular, the managers of foreign subsidiaries are instrumental in a process of organizational transformation that has resulted, in broad terms, in the shift of marketing, manufacturing, R&D and even business management functions away from the traditional centre. Unmistakably, this process can also be explained as a response to environmental change, but the point is that we have to move away from a monolithic model in which the MNC (as a whole) responds to environmental shifts, and towards one in which the structure of the MNC is created by the interplay between the actions of parent company and subsidiary managers, who both respond to and drive changes in the business environment (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Drivers of change in the multinational corporation

This is not a novel insight. Gunnar Hedlund and colleagues (Hedlund, 1986; Hedlund and Rolander, 1990), in particular, have done a very good job of explaining how the ‘new model’ in Figure 1.1 works, and the well known studies by Chris Bartlett and Sumantra Ghoshal (1986, 1989) also provide clear evidence that subsidiary managers have a substantial role to play in the emergence of new organizational responses in MNCs. Nonetheless this represents the true starting point for the ideas presented in the book. Others have examined how MNCs respond to changes in the external environment; the emphasis here is how they respond to changes from within.

Some background: research on the multinational corporation

The issue of internally driven change in MNCs will be picked up again shortly, but before it is addressed it is important briefly to review some of the recent thinking in this area. There is an enormous volume of literature in existence, much of it operating at too high a level of analysis (the role of the MNC in global trade), too low a level of analysis (various functional activities within the MNC) or from theoretical perspectives that are not conducive to discussions of management behaviour (chiefly transaction cost theory).1 What follows, then, is a brief and selective review of the MNC strategy, structure and organization literature.

The field of research that is typically referred to as ‘multinational management’ can be traced back to about 1970. Beginning with the seminal work of Stopford and Wells (1972), the focus of this early research was on broad questions of strategy and structure in MNCs. Stopford and Wells, for example, put forward a framework for understanding how MNCs shift from an international division to a global product or worldwide area structure. Franko (1974), Egelhoff (1982) and Daniels et al. (1984) primarily examined the reasons why certain structural forms are adopted.

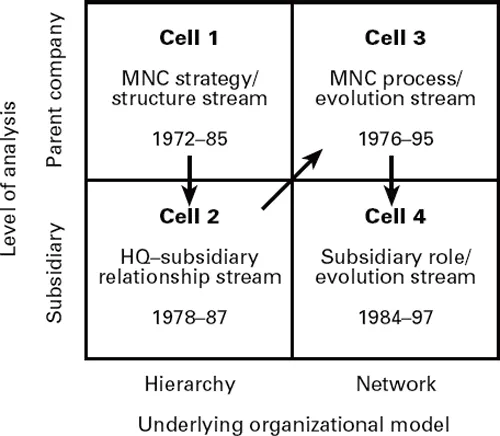

Figure 1.2 illustrates how this initial focus on corporate-level strategy and structure has evolved over the years. The studies noted above are positioned in cell 1 – they were undertaken at the head office level of analysis and they were based on a traditional hierarchical model of the MNC.2 This line of research continued through much of the 1980s, but it was then eclipsed by other approaches that seemed to offer greater potential.

The second body of research (cell 2 in the matrix) was concerned with understanding head office–subsidiary relationships. Sporadic studies of this phenomenon were undertaken in the 1970s (for example, Brandt and Hulbert, 1977; Sim, 1977) but the key reference was to a conference in Stockholm at which European, American and Asian scholars brought together a variety of perspectives on managing foreign subsidiaries (Otterbeck, 1981). This research was concerned with questions of subsidiary autonomy, formalization of activities, and coordination and control mechanisms. As with the first line of research, it was also based on hierarchical assumptions – that the subsidiary was subordinate to and interacted primarily with its parent company. Research in this vein continued through the 1980s (for example, Cray, 1984; Gates and Egelhoff, 1986; Poynter and Rugman, 1982; Rugman, 1983), but has also lost favour in recent years.

Figure 1.2 Streams of research in multinational management

The sea change in thinking that caused both these lines of research to fade away was the realization that the hierarchical model did not capture the reality in MNCs. Foreign subsidiaries often had large manufacturing and R&D activities that were as important as anything in the parent company. And rather than just engaging in communication with their parent company, many had highly developed networks of relationships with other subsidiaries around the world. Ground-breaking research by Bartlett (1979), Bartlett and Ghoshal (1986, 1989), Hedlund (1986, 1994), and Prahalad and Doz (1981) made clear the need for a new paradigm in international management. Terms such as ‘heterarchy’, ‘transnational’ and ‘multifocal’ were invented to describe better the organizational structure of MNCs.

The third line of research (cell 3) can be traced back to the work of Prahalad (1975) and Doz (1976) and followed through the various studies identified above. The focus was clearly on the decision makers in head office, and their ability to structure their worldwide operations in a way that allowed them to get the most value out of their foreign subsidiaries. While never completely disavowing the hierarchical model, this body of research has increasingly sought new ways of describing the MNC. For example Ghoshal and Bartlett (1990) have modelled the MNC as an interorganizational network, and Hedlund has suggested the ‘N-form’ and ‘nearly recomposable system’ (1994, 1997). As already indicated, such models appear to be much better descriptors of what actually happens in MNCs, and they have had a considerable influence on my own work.

The final cell (cell 4) is perhaps the one in which most research is currently been undertaken. This line of research is concerned with the foreign subsidiary as the principal unit of analysis, but unlike the earlier work in this area it sees the subsidiary as a node in a network, rather than being in a dyadic relationship with its parent company. Important early studies in this area were the Canadian studies of White and Poynter (1984) and Etemad and Dulude (1986), and the typologies proposed by Bartlett and Ghoshal (1986), Ghoshal and Nohria (1989), Jarillo and Martinez (1990) and Gupta and Govindarajan (1991). In all these studies, attempts were made to identify different types of subsidiary – some with leading-edge strategic roles, others acting as implementers or local sales offices – and then to associate certain environmental or structural patterns with each type.

The more recent variant of cell 4 research is to take a more dynamic perspective and to think about how subsidiaries actually change their roles over time. Research on Canadian subsidiaries, for example, has for a long time sought to understand how ‘world product mandates’ are gained (for example, Crookell, 1986, 1990; Rugman and Bennett, 1982; Science Council of Canada, 1980). The answer, it seems, is a long process of capability and credibility building in the subsidiary company, coupled with a significant amount of luck. Studies of subsidiary roles have begun to consider changes along the standard dimensions (for example, Jarillo and Martinez, 1990; Taggart, 1996, 1997). And a parallel line of research on the evolution of MNCs (as a whole) has also informed thinking about trajectories of development in subsidiaries (Kogut and Zander, 1992, 1995; Malnight, 1994, 1996).

I have chosen not to mention any of my own research in this brief review, but it should be obvious that it falls unambiguously into cell 4 – undertaken at the subsidiary level of analysis, and based on a network conception of the MNC. Consistent with the latter group of studies, the focus is on process issues, and on the way in which action taken within the subsidiary can influence its role in the corporation. However the focus is also broader than that of most research ...