![]()

1

Introduction

Chapter Aims:

- To introduce a cyclical coaching model that explains the coaching process

- To explain the functions of the different parts of the model, together with the important transition points

- To introduce the chapters of the book

In this book I explain how coaching works. Coaching is a facilitated, dialogic, reflective learning process, and its popularity reflects a need arising in society driven by complex situations and the individual nature of problems affecting people. But, there is a problem with coaching in that, although anecdotally we know it works, it is not clearly defined, and the research underpinning it is notably sparse. Furthermore, it is supported by a collection of loosely aligned interventions and activities, all necessarily adopted from other disciplines, but often without clear justification. Fortunately many of the components of coaching have been researched in their own right, within their own disciplines. Therefore, in this book I work from a pragmatic perspective, drawing extensively on this research in order to provide a comprehensive evidence-based understanding of coaching that will begin to explain its unique power and appeal.

I believe that as coaches we should each adopt a pragmatic approach to our work and our research. We need to recognise theories as important, but also see them as socially constructed ‘truths’ that are open to challenge. Pragmatism is derived from the Greek word pragma, meaning action. Pragmatist coaches therefore, take the theories, tools and techniques that they deem useful, employ them in their practice, and then report on their effectiveness, mapping them back to their respective theoretical origins. The pragmatic method insists that truths be ‘tested’ against practice or action. As I have explained elsewhere, I see the pragmatic approach to coaching practice as overcoming many of the flaws in current thinking about coaching:

It justifies an initial eclectic approach, appeases calls for integration, overrides a top-down, single school approach and gets us away from an emphasis on the individual coaches’ values and beliefs. A pragmatic, empirical position expands the meaning perspectives of the practitioner, takes the emphasis away from the individual as having some core of inner ‘truth’ and extends human knowledge beyond the personal knowledge of the individual, or the orthodoxy of particular theories, and outwards towards a more comprehensive, socially constructed, theoretical commons that can become a basis for a profession and a professional philosophy that all can build and share. (Cox, 2011: 61)

This then is the philosophy underpinning this book. The model of coaching presented in the book is necessarily pragmatic – it uses cognitive and behavioural science wherever they can best be useful. However, it is also essentially phenomenological and constructivist: it begins with attempts to understand the client’s experience, moves through clarification, reflection and critical thinking, which are highly cognitive, and then looks at ways of facilitating the transfer of understanding back into experience. So it goes beyond cognitive change, suggesting that the cycle is not complete until there is actual embodied, physical change as well.

In the book I also present coaching as synonymous with facilitated reflective practice. I describe how coaching begins and ends with the client’s experience, whether that is specifically workplace experience or whole life experience, and in between is a complex process of phenomenological reflection augmented by critical thinking. Beginning with clients’ attempts to articulate their experiential dilemmas, I particularly want to explain the coaching process through a lens of phenomenological reflection, beginning with how clients’ experiences lead to dilemmas that provide grounds for coaching, and ending with the resolution of those particular dilemmas via integration of new learning back into experience.

Although many books mention the importance of reflection, few really place reflective practice at the centre of their coaching universe. One text that does attempt to give a fuller account is Brockbank, McGill and Beech (2002). These authors define reflection as ‘an intentional process, where social context and experience are acknowledged, in which learners are active individuals, wholly present, engaging with another, open to challenge, and the outcome involves transformation as well as improvement for both individuals and their organisation’ (Brockbank et al., 2002: 6). Later, Brockbank and McGill (2006) focus on reflective dialogue and point out that the idea of reflection as solely an individual activity belongs to the ‘rational model of learning that suggests that the cognitive mind alone can solve any problem, sort out any confusion …’ (2006: 53). They further suggest that ‘while intrapersonal reflection can be effective and may offer opportunities for deep learning, which may or may not be shared with another, it is ultimately not enough to promote transformative learning’ (2006:53). Thus they suggest that for transformation to occur, reflection work must be undertaken with help from other people. The argument here is that, without dialogue, assumptions and unhelpful beliefs are not challenged, and so reflection is limited to the insights of the individual. Thus these authors identify the special role that ‘intentional dialogue’, such as that initiated by coaching, has in promoting reflection.

About this Book

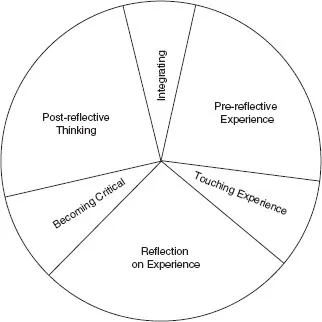

In order to structure the book, I introduce a practical and holistic model of the coaching process that shows a progression, beginning with unarticulated experience and moving through various stages of cognitive exploration towards the integration of reformulated understanding that informs future experience. In order to make the structure of this process clearer, I introduce here a new cyclical coaching model (Figure 1.1). The model has spaces and spokes, like a wheel, which are all key stages necessary to help clients transition through the coaching assignment.

Skiffington and Zeus argue that coaching demands ‘a conceptual framework that will provide a common language and a basis for research and create a blueprint for coaching practice and education’ (2003: 29). This book is an answer to that demand. It is also an answer to Jackson’s lament that coaching is not being based on theory: ‘The fast growth of the coaching industry has created structural weaknesses’, he argues, adding that ‘it is never too early to attend to foundations’ (Jackson, 2008: 74). This book then, heeds Jackson’s call and is part of that constructive investigation into the foundations of coaching that is so badly needed. I hope that the book will provide a strong underpinning for coaching so that others may build confidently on its ideas and proposals.

Underneath the frequent calls in the profession for dialogue about the future of coaching lies an inherent lack of understanding about what coaching is and what it can do. Sometimes we have been starting our investigations in the wrong place. I have watched coaching researchers focus on exploring sites of application through numerous case studies and have watched them grasp at attractive theories and models from a range of disciplines, particularly psychotherapy. What I have not seen yet is an explanation of how coaching works or why it works – the fundamental process that underpins all coaching. Furthermore, in a struggle to find an identity, coaching has tried to identify boundaries between itself and counselling or mentoring or training (Bachkirova and Cox, 2005; Lawton-Smith and Cox, 2007). But its identity has also been blurred by adoption of techniques from other fields. By explaining in this book how coaching really works, I uncover fundamental differences that will enable coaching researchers to focus more explicitly on the process of coaching as a distinct area of study.

Coaching is multidisciplinary and there are many established and effective approaches that enable coaches to work in a number of different contrasting or overlapping ways (see Cox et al., 2010, for examples). However, I would argue that a fundamental process underpins all coaching, and it is this process that informs how it differs from other helping approaches such as mentoring and counselling. Thus the book provides a new, holistic and very practical model that gives clients an understanding of the process, and provides coaches with a framework to guide their practice – and indeed to underpin their own learning and development.

There are lots of books about coaching. They mainly talk about the psychology of coaching, how to do coaching, the coaching process, or the role and benefits of coaching in a variety of different contexts. But an unambiguous extended definition of coaching remains elusive, and the workings of the coaching interaction itself are still a mystery. This book plugs that gap. It makes clear what happens and why it works. It uses theory and examples of coaching dialogue to build an understanding of how all the basic elements present in the coaching interaction (questioning, listening, challenging, reflecting, etc.) work and interact, and thereby exposes the inscrutability that underlies coaching’s success as a personal and professional development intervention.

About Coaching

When clients first come to coaching it is often because their recent experience has driven them there. Something needs to change or improve, or something within their pre-reflective, experiential ‘soup’ has bubbled through to become conscious. It might be that they have a hunch, a feeling or an intuition that is troubling them. In Mezirow’s (1991) terms they may have a disorienting dilemma. The dilemma may have arisen from a sudden feeling that something is not right, or it may be something that has built up in importance over time and one further event has tipped the balance. Either way, they feel that something needs to change and that is what brings them to coaching.

The issues a client may bring to a coach may be feelings of being stuck, feeling as if no progress is being made, frustration that the same thing keeps happening, or a feeling of going back and forth with no apparent resolution. Intuitively, people in these situations feel that they need to make changes or they need support at work to overcome an impasse. They may come to coaching feeling that they are at a point of transition. They often feel they are on the cusp of something, or that something needs to alter, but they are not clear what. The coach then needs to help the client identify the nature of the experience in order ultimately to inform necessary change. Other clients may be clearer about where they want to be in their life, but they still want help getting there.

The Coaching Cycle

Very many coaches want to work holistically, but do not have access to an evidence base to enable them to do that. The cyclical model described in this book explains an holistic approach that satisfies that need, and, I would argue, actually underpins all coaching. The model has client experience at its core and takes account of a comprehensive range of theories, including experiential learning, intuition, focusing, phenomenology, critical reflection, rationality and tacit understanding, and also draws on current thinking in neuroscience in order to consider how our thinking and reflective faculties are linked to emotions and brain function.

The Experiential Coaching Cycle (shown in Figure 1.1) has three substantive constituent spaces: Pre-reflective Experience, Reflection on Experience and Post-reflective Thinking. Each space is a hiatus where events occur or reflection happens. The cycle also has three major ‘spokes’, or transition phases: Touching Experience, Becoming Critical and Integrating. Spokes invariably involve more emotional, cognitive or physical effort than spaces, and are particularly challenging for both coach and client because of the emotional struggle and uncertainty inherent in them. These spaces and transitions are described further below.

In developing this cycle I owe an intellectual debt to Kolb (1984; Kolb and Kolb, 2005). Kolb explained in detail how knowledge results from ‘the combination of grasping and transforming experience’ (Kolb, 1984: 41). What drives clients to come to coaching are events in their everyday experience, and what they need then at the end of the coaching is to take the enhanced, often transformed, understanding back into their everyday life. In his experiential learning cycle Kolb (1984) identifies an active experimentation phase as well as three other learning phases: concrete experience, reflective observation and abstract conceptualisation. During active experimentation, Kolb suggested, the new understanding, gleaned through earlier phases equips learners to do things differently.

Figure 1.1 The Experiential Coaching Cycle

However, although the Experiential Coaching Cycle owes a debt to Kolb, it differs from that earlier model in its emphasis on the transitions. What is missing from Kolb’s learning cycle is a discussion of the transition from one state of being to another. Between his ‘bases’ of concrete experience and reflective observation, for example, I would argue that there is much uncertainty for the individual; there is transitory activity which necessitates dialogue and support from a coach. The Experiential Coaching Cycle foregrounds those transitory points, or edges, where much learning occurs. Interestingly, Brockbank and McGill (2006: 57) also identify reflective dialogue as engaging clients ‘at the edge of their knowledge, sense of self and the world’, and other authors that I draw upon in this book, such as Gendlin, Claxton and Fitzgerald talk about ‘edges’. In describing the cyclical model, I refer to these edges as spokes because, although they feel edgy, they also have a driving effect, motivating clients and moving them towar...