- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Identity and Organizations

About this book

An understanding of identity is fundamental to a complete understanding of organizational life. While conventional management textbooks nod to in-groups, cohesion and discrimination, this text offers instead a deeper, more nuanced understanding of why people, groups and organizations behave the way they do.

With conceptions of identity perhaps less stable than they have ever been, the authors make complex theoretical issues accessible to the reader through the use of lively examples from popular culture. The authors present an overview of the key issues, as well as an examination of cutting-edge research and topical forces currently re-defining identity, such as globalisation, the fair trade movement and online identities.

This text is a succinct, relevant and exciting overview of the field of identity studies as it relates to business and management and applied social sciences, an is an invaluable resource to undergraduate and postgraduate students of management on any course that has an identity component.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Understanding Identity and Organizations by Kate Kenny,Andrea Whittle,Hugh Willmott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Organisational Behaviour. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

| Introduction to Understanding Identity | 1 |

1.1 Introduction

Identity is a topic that is relevant to everyone. Identity relates to the timeless question: ‘who am I?’ and the related questions: ‘who and what do I appear to be: to myself, to my friends, my boss, my bank, my neighbours, my lecturers?’. A person can appear to be many things at once, even where these different ‘identities’ appear inconsistent or even contradictory. Someone could be, for example, a politically conservative, religiously atheist, homosexual female surgeon. All these words act as categories that describe us in different contexts. Such identifiers are vital to our experience of life, both at work and outside of it. In effect, they act as landmarks as we navigate or negotiate our way through social landscapes.

Some aspects of our identity are hard, but not necessarily impossible, to control. Sex, height and colour of skin are all difficult to alter, but they can in some cases be changed – in the case of transsexuals, for example. Other aspects, such as religion, hobbies and occupation, are more open to being changed, managed and controlled (Muir and Wetherell, 2010).

We sometimes hear about identities being ‘strong’ or ‘weak’. Fanatical sport team supporters, such as so-called ‘football hooligans’, who have fights with other people simply because they are supporters of rival teams, could be said to have too ‘strong’ a sense of identification (see Glossary) – a strong sense of belonging and attachment with their team and fellow supporters. In extreme cases, people are murdered simply because they are members of a rival street gang, to protect the ‘honour’ and ‘reputation’ of the gang. In contrast, other identities are thought to be too ‘weak’ nowadays. Attachment to the local community, for example, is often said to be weaker now, and this is associated with a breakdown in social cohesion and community spirit.

We see the importance of identity in work organizations too. Sherron Watkins’ role at Enron illustrates this point. Watkins was a Vice President for Corporate Development. In August 2001, she tried to alert the CEO at the time, Kenneth Lay, to the presence of accounting irregularities within the company, which she felt were dubious and possibly illegal. As the corporation began to collapse, she advised her CEO to come clean and report its massive financial losses to investors, but the result was a sidelining of her role in the organization. When Enron was eventually brought down, with catastrophic effects, Watkins testified before US Congressional Committees that investigated Enron’s business practices.

In subsequent interviews, traces of Watkins’ sense of identity, and her multiple identifications, emerge. She describes herself as a professional accountant, a moral person and an Enron employee, citing all three as contributing to her sense of self – who she is (and was). In particular, she points to the importance (or ‘strength’) of her sense of professional values that were embedded during her training as an accountant which, she says, equipped her with an ethical sensibility and a moral perspective on the world:

I started my career in the early 1980s at Arthur Andersen & Co. as an auditor. I have to say that it bothered me that we were told it was not a public accountant’s job to detect fraud. We were told to maintain a healthy degree of skepticism, but our audits were not specifically designed to find fraud. The trouble is that most shareholders believe the opposite: that an audit does in fact mean auditors looked for signs of fraud. ... Being an ethical person is more than knowing right from wrong. It is having the fortitude to do right even when there is much at stake. (Carozza, 2007)

Watkins recalls how, early on in her career, she experienced some conflict between two key elements of her identity: an accountant and a Christian (she discusses God and Enron in ‘The Enron Blog’ by Cara Ellison (2010), 17 November 2010). As time passed during her period at Enron, she became aware of the dubious ‘creative accounting’ taking place at her firm. Her identification with Christian values and professional ethics came into conflict with her identification as an Enron employee. She grew uncomfortable with wrongdoing that appeared to be at odds with the values that were central to her sense of identity. This conflict led her to ‘blow the whistle’ (see Figure 1.1) on her close colleagues by drawing her concerns to the attention of her boss, Ken Lay. In an interview that took place after she had publicly spoken out, Watkins said:

The real lesson for me is that I should have left Enron in 1996 when I first saw behavior that I thought was over the line. If your own personal value system is not validated or if you are uncomfortable when your value system gets violated, leave that organization. Trouble will hit at some point. (Lucas and Koerwer, 2004)

Watkins’ self-identity – how she saw herself – played an important role in her decision to expose one of the largest and most significant corporate scandals of the last century.

Figure 1.1 Corporate whistleblowers

What the Sherron Watkins example shows us is that workplace identity is a vital part of working life and has significant implications for ourselves and for those around us. This book focuses on the relationship between identity and workplace life. Our particular focus is upon how identities are shaped in and through organizations, such as accounting firms, Enron and religious institutions. By ‘organizations’ we mean anything from a large corporation, to a small family business, a single subcontractor, a public sector organization, a charity or voluntary organization – anywhere where people work that is formally organized and structured, whether paid or unpaid.

1.2 Identity vs Personality

Often the terms identity and personality (see Glossary) are used interchangeably, or are assumed to have rather similar meanings. Words can, of course, acquire all kinds of meanings, so we are not suggesting that ‘identity’ has any essential meaning. Here we are simply concerned to communicate how we intend to define and use the term ‘identity’ and, to do this, we distinguish it from ‘personality’.

At first sight, the terms personality and identity seem very similar. They both seem to be about what makes us ‘who we are’. For us, however, the terms signify quite different things. The term personality tends to be associated with a person’s unique and distinctive ‘inner world’ and is widely used in the discipline of psychology. It refers to the idea that we have a distinct set of inner cognitive (i.e. mental) structures and processes (such as attitudes, dispositions, temperaments and stereotypes) that influence how we behave. For example, some people are considered to have a ‘shy and introverted’ personality while others are ‘outgoing and extrovert’. These inner cognitive structures are understood to be either genetically predetermined (i.e. we are born with them), or formed primarily during the early stages of childhood – making them ‘hard-wired’ into the brain and therefore difficult to change. Social scientists study personality differences by using scientific methods such as tests, questionnaires and experiments. They attempt to categorize the different types of personality and study how personality types influence behaviour. They rely on the assumption that human beings are discrete, independent entities with unique characteristics.

The term identity, on the other hand, can be attributed to groups as well as individuals. Indeed, membership of a wider group is key to specifying and understanding identity. So, for example, Sherron Watkins understood herself in terms of being an accountant and a ‘Christian’, both of which indicate membership of a wider group (of accountants and Christians). In contrast to the term personality, reference to the term identity signals an approach to understanding ‘who we are’ that is found in the fields of sociology, politics, cultural studies and discourse studies. Identity, even self-identity, does not refer to a distinct set of inner cognitive (i.e. mental) structures, processes or dispositions. Rather, it refers to how a person makes sense of themselves in relation to others, and how others conceive of that person. Identity can refer to individual characteristics (such as being an ‘outgoing person’), which may of course include ideas about the kind of ‘personality’ we have, as well as to social categories (such as ‘being a gay person’).

So, identity can include identification with elements that we call ‘our personality’. But this approach does not treat such elements as ‘hard-wired’, genetically predetermined features of the brain. In general, identity refers to socially available categories, which can of course include how we think about our ‘personality’. These categories provide ways of making sense of ‘who I am’ in relation to ‘who you are’. Whereas the psychological use of the term personality assumes and refers to the existence of a comparatively rigid and unchanging set of cognitive structures or mental processes, the sociological term identity is conceived to be contingent upon the particular – local, cultural and historical – conditions of its production. In other words, identity varies according to:

- Local context (e.g. my identity at home vs my identity at work).

- Culture (e.g. what it means to be a man in Chinese society vs American society).

- History (e.g. what it meant to be a man in the twelfth century vs today).

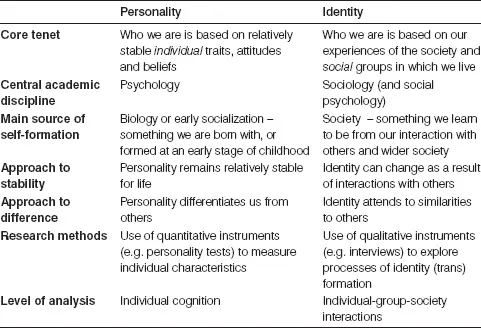

The concept of identity helps us to appreciate how our ways of making sense of ourselves and others are influenced by social processes. Such processes include the local, day-to-day interactions we have with friends, family and colleagues as well as the broader context of the society and period of history in which we live. Consider the type of person who respects tradition and authority figures, who has a strong sense of ‘duty’ to others – which can be regarded as a ‘personality trait’. Those interested in ‘personality’ might attempt to use personality tests to measure the differences between people in respect of their sense of duty and respect for authority. When engaging a sociological focus on ‘identity’, the emphasis shifts from individual differences to the social conditions that produced this type of ‘personality trait’. For example, think about the differences between those born into so-called ‘honour-bound’ cultures, such as parts of India or China, where a strong sense of duty to the family and to (male) elders is upheld, with those born into the more ‘individualistic’ culture of North America. Table 1.1 outlines the main differences between the two concepts.

Table 1.1 Personality and identity compared

An attentiveness to ‘identity’, we believe, helps to compensate for some limitations of studies that place ‘personality’ at their centre. Among these limitations are:

- A view of people as atomistic, sovereign agents: that is, as isolated individuals who either have complete control over who they are, or are the prisoners of their ‘personalities’.

- A reliance on the idea that our sense of self resides ‘within us’, as an essential feature of our cognitive make-up.

- A use of a power-free analysis: that is, the focus on personality ignores the role of power in shaping and directing processes of self-formation.

The value of a focus upon identity can be summarized as follows:

- It appreciates how people’s sense of ‘who I am’ is embedded in social relationships.

- It views identity as a social phenomenon, based on (more or less dominant) collective understandings of what it means to be a person, rather than existing only ‘inside our heads’ as mental processes.

- It emphasizes the role of power in shaping our sense of self, including the reproduction of diverse forms of inequality (e.g. gender, ethnicity, class structure, etc.).

We will not be discussing ‘personality’ per se in this book. But we will be exploring many themes and issues that are highly relevant to anyone who is interested in ‘personality’. That is because students interested in ‘personality’ are usually inquisitive about how they, and other human beings, behave: what makes them ‘tick’. Studying identity, we will show, can provide penetrating insights into ‘human behaviour’ that are different to, and so can complement and perhaps surpass, those generated by studies of ‘personality’. So, for example, applying a personality test (e.g. Myers–Briggs) to Sherron Watkins might help us to understand why she, rather than some other Enron employee, sent the ‘whistleblowing’ internal memo to her boss, Ken Lay. But, to understand the way she alerted her superiors in Enron, how and why she eventually decided to ‘go public’, might be better understood by considering her diverse and perhaps conflicting identities and institutional affiliations, as a loyal employee, as a Christian, as an ambitious accountant, and so on.

1.3 Identity on the Management Agenda: A Brief History

When did the notion of identity first get onto the management agenda? Early approaches to management, such as F.W. Taylor’s Principles of Scientific Management (1911), viewed a person’s identity – our affiliations with others and the thoughts, feelings and values which make up our sense of who we are – as an obstacle to effective management (Rose, 1988). Taylor thought that management shou...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Summary of Contents

- Contents

- About the Authors

- 1 Introduction to Understanding Identity

- 2 Theoretical Perspectives on Identity

- 3 Diversity and Identity

- 4 Occupational Identities

- 5 Identity and Organizational Control

- 6 Organizational Identity

- 7 Virtual Identity

- 8 The Future of Identity

- Glossary of Terms

- References

- Index