![]()

Chapter 1

#Still Human

Into the Glare of the Public Square

PART ONE. THE GREAT DEMOTIONS, UPDATED

Like racism and sexism, ageism has a history. Much that has lately occurred with regard to old age and aging relations is historically quite peculiar. The production of age is like the cunning of bankers: the evils never stop mutating. Our best cultural analysts scramble to keep up, which means that discoveries about later-life demotions are slow to emerge in the public square. The state of the ageisms (as it is sometimes useful to call them) begs for constant updates.

Although the term “ageism” was invented in 1969, a year after “sexism,” “sexism” found early hard-won success: taught in classrooms, a boon to consciousness-raising, the source of damning epithets like “sexist pig.” Unlike all the bigotries now recognized as evils (among them sexism, racism, homophobia), “ageism” has yet to become an everyday pejorative. But this is not because the reality has ended.1 It is rarely named and little examined, even in gerontology. (Institutionally, the field started to highlight the lack of study of ageism in 2015).2

People may mistakenly think ageism is behind us because of federal, state, and local agencies serving older people—the agencies that remain after Congressional budget-slashing and means-testing since 1983.3 These are “service-oriented” responses4—Social Security, Medicare, Older Americans Act, Meals on Wheels, the programs of AARP, OWL (formerly the Older Women’s League); plus the statutory attempts to end various discriminations (in the USA, the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, ADEA; the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, EEOC; and the private NGO, Justice in Aging). Activists anywhere may turn for inspiration to the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing; HelpAge International; the UN’s International Day of Older Persons, which focused on ageism in 2016; and the European Union’s Charter of Fundamental Rights and its Employment Equality Directive. Welcome as these documents and programs are, in many places they do little to temper a frosty climate. And the statutory plethora supports an illusion that struggling against the powers-that-be is no longer urgent.

In the United States, Obamacare is a rare, particular, midlife boon, even though rates rise higher for midlifers. Before the Affordable Care Act, the high death rate suffered by people over fifty-five who were uninsured and too young for Medicare’s rescue was a scandal. Annually, 10.7 percent of them were dying.5 Breaking Bad, a dramatic series that proved obsessively watchable, ended the night before Obamacare went into effect on October 1, 2013. This was no coincidence. The show began in 2008, at the very beginning of the unending Recession, when unemployment became terrifying. A timid high-school chemistry teacher, Walter White, works two jobs, each demeaning. He learns he has lung cancer the day after his fiftieth birthday. Treatment is possible but White’s insurance is inadequate and he’s broke. He resorts to manufacturing meth. White’s transformation from a midlife loser to a drug-dealing killer kept the plot churning. His widely shared conditions—his age, malignancy, lack of job prospects or insurance, maybe even Bryan Cranston’s whiteness—made the show plausible and affecting. By offering subsidized health insurance to people like White, Obamacare forced the series to end and alleviated the anxiety or grief of millions.6 By the spring of 2014, the number of people fifty-five to sixty-four signing up was greater than insurers had expected but not more than age critics had anticipated.7 A coalition of progressive groups led President Obama to turn around and argue for expanding Social Security’s Cost of Living Adjustment (COLA). But the material side of helping a poorer, sicker population is used as an argument against indispensable government programs.

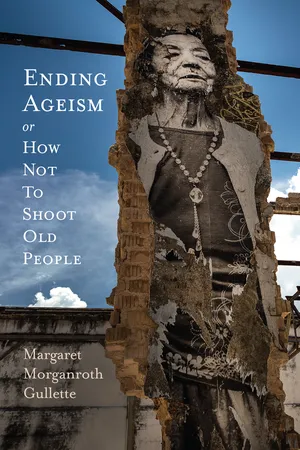

Much as I might wish to salute progress in a book like this, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People is not a progress story. It strives to answer the questions, How do we recognize ageism now? How bad is it? How might we best try to end it?

The safety nets end, insofar as they do, only what might be called the “first-generation” issues, like health care and medications, that had clear policy solutions. My historicizing language is taken from Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, discussing worsening racialization when the Supreme Court majority gutted the Voting Rights Act. #BlackLivesMatter tells us Ginsburg was right to dissent.8 Old people should also be included among those losing fundamental voting rights: in many states the new ID requirements will disenfranchise those (often people of color and immigrants) who do not have access to their birth certificates. The second-generation issues of ageism that this book deals with tend to be immune to legal and institutional efforts, less visible than the first, and increasingly devastating and intractable. Many also have lethal consequences, but they do not come with hashtags.

Here are a few updates on exclusions and demotions for which it is hard to prove discriminatory “intent” but easy to recognize discriminatory outcomes.

Midlife men used to be considered prime-age workers at the peak of their experience and ability. The stories and data on midlife job discrimination are appalling. Related to unemployment outcomes (beyond divorce, home and farm foreclosure, children dropping out of college) is midlife suicide. The unending recession saw a sharp rise in suicides of unemployed men. The steepest rise was for men age fifty to fifty-four—almost 50 percent more. A Baltimore man lost his job at the steel mill at Sparrows Point, where he had worked for thirty years. At age fifty-nine, Bob Jennings couldn’t get into a retraining program. He felt he was a failure with no future. “‘No no,’ his wife said, ‘The system is the failure,’ but she couldn’t convince him,” and he shot himself.9

Although recognizing that “ageism is not experienced over the entire life course, as racism typically is,” a professor of public health, J. O. Allen, nevertheless finds that the mechanisms of body-mind distress work similarly. Studying this kind of ageism is in its “infancy,” Allen says, but she sees evidence that “repeated exposure to chronic stressors associated with age stereotypes and discrimination may increase the risk of chronic disease, mortality, and other adverse health outcomes.”10 And once you are ill, many specialists treat you differentially, denying not-so-very-old people with lung, colorectal, and breast carcinomas, and lymphoma the life-saving treatments they would offer younger people, though the former could benefit as much. The odds of not receiving chemotherapy if you are a woman over sixty-five with breast cancer are seven times greater than for a woman under fifty.11 Undertreatment of older patients may be a primary reason for their having poorer outcomes than younger patients.

For doctors, aversion to the old as patients starts young. Although compassion can be taught, almost every exhausted impatient medical resident is warned about GOMERs—Get’em Out of My Emergency Room: older people with complex problems. (Nurses don’t seem to get that tainted message.) GOMERS are said to “block” hospital beds. Older people who come in sick may leave disabled, if medical staff fail to feed them properly or control their pain.12 The health of people on Medicare is represented in the mainstream media as being protected, even cosseted, but malpractice with an ageist/sexist edge should sharpen our second-generation focus on doctors, hospitals, and medical training.

Now Alzheimer’s has been inextricably shackled onto old age. Neuroageism prophesies that any of us might dodder toward death, as Alexander Pope said of Jonathan Swift, as a dribbler and a show, only now more expensively than was ever before possible. In the Age of Alzheimer’s, as medical/pharmaceutical entrepreneurship bumps up against the heightened terror of memory loss, we may be called “demented” while still having wit to deny it. Normative ideals deem all of us, eventually, unsuccessfully aging. An Internet hate site wishes that “these miserable old once-were-people not survive as long as possible to burden the rest of us.”13 In chapter 3, on teaching age in college classrooms, I refuse to dismiss troll slobber, because many sober pundits also complicitly foretell how awful it will be to live on into old-old age. In Congress, partisan deficit-mongers want the “gray tsunami” to renounce Medicare as soon as our cancers need treatment. Supposedly we owe it to ourselves and our offspring, not to mention the budget, to “not survive as long as possible.” The supposed demographic “catastrophe” of longer life—a stressor our grandparents didn’t have—has taught many to dread a future of “becoming a burden” or taking one on. We are meant to let ourselves ebb by nature, accepting our “duty to die” as a patriotic imperative.

Dehumanization is the inevitable outcome of having a culture that relentlessly questions the value of the later-life age classes. Like other critical gerontologists, two highly regarded British theorists, Chris Gilleard and Paul Higgs, also see the trend worsening. “While the putative abjection of those with an appearance of agedness can be and is being challenged,” they noted in 2011, “other linked processes have been at work bringing about an intensification of agedness.”14 They refer to “real old age,” but a person can be targeted while still ensconced in what I call “the long midlife.” Younger people can’t tell the difference between us. In our current frigid eugenic imaginary—a twenty-first-century repeat of Anthony Trollope’s Fixed Period (1882), in which sixty-eight was the literal deadline—it’s as if “the appearance of agedness” is becoming forbidden.

In this atmosphere, wife-killing is rising among male care-givers over fifty-five. A sixty-eight-year-old Ohio man, John Wise, brought a gun to the hospital and shot his wife after she had had triple cerebral aneurysms. He knew she was already close to death.15 As chapter 6 reveals, wife-killers who plead “euthanasia” rarely do time. Sometimes they are not even indicted. The legal regime shows that government can accept a “right to kill” old people. Not all old people, of course. These old women appear to have a lessened claim to the protections of the state. In the following chapters—called, in a judicial metaphor, “sessions”—I explore further the kinds of suffering that are unprecedented and unseen, engendered by ageism’s growing global power.

“Old age” can be represented as becoming deficient in the ways an unequal economy demands and a decline rhetoric confers. “The old,” visual spectacles of decrepitude, are either feeble, unproductive, or demented, appropriate objects of revulsion, or politically powerful Boomer voters whose job security is so unassailable that they do not need a COLA or the heightened scrutiny of constitutional law. The age group can be held responsible for an increasing portion of the national crises (fiscal deficits, high youth unemployment), serving as a scapegoat, a bogeyman, a mass of hysterical projections.

Movements that have made progress—feminism, antiracism, gay rights—also reckon with disastrous failures while trying to counter the ascendancy of market ideology, the relentless undermining of welfare states, political slyness, popular ignorance, and ethical laxity. But they are nevertheless mainstream movements. Lacking its own passionate movement, ageism remains the most stubbornly, perplexingly naturalized of the isms. Although bias is sometimes driven by malice, aiming to wound the Other, often blows are aimed at a nonhuman target (like deficit-reduction or casual profiteering). This enables the perpetrators to ignore the human victims whom they are creating. Damaging those of us who are aging past midlife almost never damages the professional or political careers of perpetrators or puts thugs behind bars.

Everyone should be concerned about ending ageism. Many people care and are open to enlightenment. Some may be frustrated at not finding an anti-ageist political interest group to join. But the distracting power of decline discourse distances the well-disposed from seeing how great the need is for truth and justice. And beside the benign reason already cited for this detachment—believing democratic governments already provide well for “them”—there is another cause of not knowing what to do next. “We do not have a well-developed language for arguing . . . against things that we never imagined people would seriously propose.”16

Blindsided

People feel confused about what assails us. Many forces hostile to the no-longer-young (including decisions already mentioned, by the Burger, Rehnquist, and Roberts courts and the 114th Congress) are not clearly identified as ageist. I speak here both as one of “us” and as an age critic who has had to work to clear my own way through the confusions.

And many are held under by the affects that ageism foists on them, understandably reluctant to identify with our defamed age class. They feel shame, dread, depression—the psychosocial sorrows that Ralph Waldo Emerson movingly noticed so long ago. Once they have suffered an attack they see as “aging”-related, further painful experiences may loom as inevitable. They blame their “aging,” and, oblivious of ideology, perceive no escape. They transmute the cultural attacks into what Audre Lorde called “the piece of the oppressor planted within” us.17 Having been shoved out houseless into January’s frigid weather, they act as if they deserve to shiver. The most worrying, we’ll see later, are those in whom self-dislike leads to despair or for whom desperate exclusions lead to suicide.18

This unhappy range of feelings ought to be identified as outcomes of ageism. Cognitively, people are pressured to accept this social construction, where old age is vilified, as if it were natural. They don’t feel sure what the word means. Popularly, it’s trivialized, as someone offering you a seat on the bus, rather than specified as letting midlife jobs be outsourced to Asia, not being offered a hopeful treatment, being shunned for some impairment. Some think it is unconnected to them. A woman who asked me the title of this book then joked, about her ninety-one-year-old father, “I’d like to shoot him.”

We can’t repudiate an evil we don’t recognize. The abstract terms in use—attitudinal bias, job and credit and judicial discriminations, disparate treatment...