![]()

1

Intersections

Gender, Class, and Caste in Nepal

Arriving in Vishnupura from Kathmandu, the bus stops in the social and economic center of the sprawling town.1 Here the streets are lined with chiya (tea) stalls—one-room snack shacks of sorts with fried treats, momos (steamed dumplings) and chaau-chaau (ramen noodles, Nepali style) that sometimes double as a poor-man’s bar—and a variety of open-air shops offering all the services one might possibly need, though on a small scale. A surprisingly diverse array of goods could be produced upon request at even the smallest one-room hardware store or medical shop. The main intersection in the bazaar is flanked on one side by the row of buses and micros waiting to turn around and head back to Kathmandu with their returning passengers (mostly human, but an occasional goat or sack of rice or vegetables was not uncommon). Much of the bazaar has been built up around a famous Hindu temple, and the temple grounds and makeshift stalls selling various religious artifacts necessary for pujaa (making an offering in an act of devotion or worship) dominate a large portion of the bazaar. Stalls filled with vivid flowers, fruit, uncooked rice, leaf plates, and multicolored braided string necklaces create a colorful approach to the temple entrances, mostly serving the many out-of-town devotees who need to purchase these items upon arrival.

I lived across the street from the mandir (temple) in a four-story concrete building with the standard rooftop patio (kousi). The ground floor of the building was rented to a momo stall and a bangle shop, the second floor rooms to renters, and the third and fourth floors were the home of a Nepali family who over a decade became my second or “adopted” family. This spatial arrangement is typical for the buildings in the bazaar, as was the rectangular, concrete building style. It is common to see bundles of iron rods sticking out of the top of a single or two-storied home, a sign that the family could not afford additional levels at that time but has plans for another floor. Home loans were unheard of, so families built and purchased as cash became available. The flat, open patios on the roofs of the building were the location of many daily activities such as drying chilies or wheat, hanging clothes to dry, or doing any activity that could be taken outside for the warmth of the sunshine during the winter months. My adopted Nepali family, like most families in the area, did not bother with the portable heaters that were available on the market at that time, so escaping the penetrating chill of indoors during the day was a great pleasure.

The kousi was also the perfect location for watching the world go by, a most appropriate phrase to describe observing the daily movement of people and goods from a house located on the only road leading down into the bazaar and toward Kathmandu from the upper regions of the Village Development Committee (VDC, an unincorporated rural area composed of nine wards, less developed than a Municipality). From this vantage point, the street and the temple grounds were below. This meant that the music played by hired bands for wedding processions would beckon from the street below, especially during wedding season. All-night sessions—sometimes lasting several days—of special musical praises to the gods (bhajan) were clearly audible from the house. This ceaseless singing/chanting, usually by a priest and accompanied by a harmonium, was projected by a loud speaker. I dared wonder aloud once or twice if god, too, did not have to sleep.

While having our morning cups of chiya leaning on the wall of the kousi, we would discuss the parade of uniformed school children of all ages in their pleated skirts, slacks, and ties holding hands or teasing one another, men and women with wage-earning or salaried jobs hurrying to reach the office on time, and a handful of expatriate families in their sport utility vehicles avoiding potholes and pedestrians, as they all made their way down to various destinations in the valley below. Another fixture on the street below in the early days of this research in 2003, though her presence was not as predictable as the flow of students and workers, was a homeless woman who, according to locals, had multiple personalities who spoke different languages. Her rants while standing on the corner became part of the normal life of the street, until one day she was simply gone. Gangs of street dogs prowled the street and alleyways, looking for food and defending their territory against newcomers. During the hot season just prior to the monsoon rains, whiffs of putrid air would circulate around the bazaar from a combination of garbage and human waste. In 2003–2004 there were open gutters lining the street into which sewage sometimes “leaked” or was improperly disposed. (An underground pipe was installed by 2005). The coming and going of tourists on special holidays associated with the mandir, along with community events on the temple grounds on special occasions, were also part of the normal progression of weeks, months, and years. During the harvest season for wheat, one or two enterprising families utilized the vehicular traffic on the paved road in front of their houses to separate the wheat from the chaff. Thus the street was a stage to many social interactions and routines.

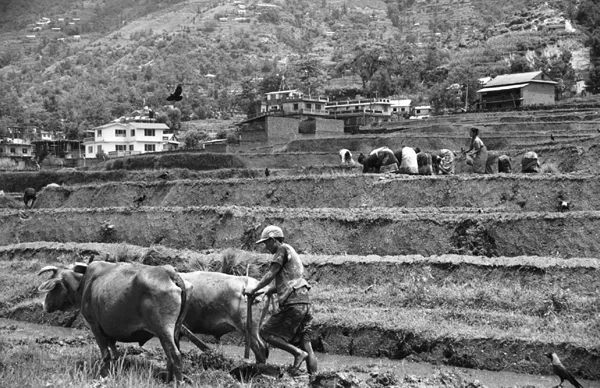

The paved road around the mandir gave way to dirt as one traveled farther up the mountainside. However, with the rapid pace of development in this community, a project to pave it had begun by my return in 2005, and by 2010 even the steeper, less populated road that runs roughly parallel to it had been partially paved. As one heads uphill, the houses become more spread out, mud and brick houses of the traditional architectural style become more plentiful, and agricultural fields and boulders begin to dominate the landscape. And yet, of course the community will continue to grow, and these rural attributes are likely to disappear. In 2003–2004, the buying and selling of land was one of the most profitable businesses available to locals. The real estate in the upper region of this area was coveted by wealthy Nepali and expatriate families alike. The land overlooked the Kathmandu Valley, it was above the layer of air pollution that plagued the valley, and the nearby mountain ridge promised a lack of development on one side. In addition, the hot season was several degrees cooler than in the valley floor below because of a combination of several factors, not excluding the altitude and the partial blockage of the morning and evening sun by the surrounding ridges. The increase in the value of land resulted in some long-established local families selling their land for a substantial windfall of cash and experiencing a dramatic change in lifestyle, and in the irony of some families who continued their agricultural lifestyle living in poverty on land worth more than they would otherwise see in a lifetime.

Fig. 2. A man plows and women plant rice in one of the terraced fields in Vishnupura.

The two roads that travel up the mountainside lie in the stretch of land that has the least intensity in slope, and several side roads jut off in either direction. After a short stretch of flat land on either side of the roads, the incline gradually becomes sharper. In 2003 only footpaths winded up these steep inclines, and a walk to or from the bazaar would take approximately thirty–forty minutes in one direction. Each year when I return, more roads have been paved and more houses have sprung up. Despite signs of rapid development, as of 2012 these higher, more remote areas (colloquially referred to simply as “maathi,” or “up there”) still retained a more rural feel and way of life than the bazaar below.

As an anthropologist, I was drawn to this location for its geographic and demographic characteristics. Geographically this VDC is located at the periphery of the Kathmandu Valley, poised on the rim of the valley with the urban metropolis below and the rural expanse beyond the ridge of mountains that encase the valley. Its in-between status, neither a village nor a city, meant that it was a middle ground between two extremes that dominate life in Nepal—that of crowded, cosmopolitan Kathmandu (and a few other such cities) and rural, remote, “village” Nepal. Vishnupura’s location and semi-urban status made it an ideal place to study social change. It was a manageable microcosm of social change in motion.

Fig. 3. The research community sits just below the northern ridge of the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal.

The other reason for selecting this site was the distribution of ethnic and caste groups represented in its population. For its small size, Nepal contains an impressive amount of ethnic and linguistic diversity. Limiting the present study to a cultural subgroup of the nation’s diverse population was necessary in order to limit cultural variation. I chose the group whose ideologies had been dominant both politically and socially since the consolidation of the country in 1768 until the overthrow of the Hindu monarchy in 2007: Parbatiya (hill dwelling, referring to the middle hills region of Nepal) Hindus. This group includes Brahmin (or Bahun), Chhetri, Thakuri, and Dalit.2 The Parbatiya group is distinct because of its social and linguistic history, but ultimately it is a loose approximation of a cultural group that is heterogeneous because of the jaats or subgroups (often glossed as “castes”) that comprise it as well as the increasingly porous boundaries that demarcate it. In order to avoid the reification of the name “Parbatiya” as a “culture,” I prefer to use the more accessible and general term, “Hindu-caste.”

After obtaining census records from the Central Bureau of Statistics and charting the ethnic breakdown of a few potential research sites, Vishnupura emerged as an ideal site because of its large percentage of Hindu-caste residents (unlike many of the predominantly Newar towns around the edges of the Kathmandu Valley).3 It also turned out that this location was not directly affected by recruiting or violence associated with the ongoing Maoist People’s War, which was a significant barrier to doing research outside of the Kathmandu Valley at the time.

During the thirteen months of research carried out between 2003 and 2005, I used a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods that incorporated ongoing participant observation, the enumeration of households and a survey of a random sample of households, the selection of thirty case studies representing a range of important cultural and economic factors, interviews and observations at the local sub-health post and the two hospitals used by locals, and immersion in family and community life by becoming the paying guest of a local Newari family and participating in daily life and rituals. My status as a fictive daughter of a local family provided me with credibility in the community and significantly aided in my acceptance. And, more importantly for the long term, I gained what has truly become a second family over many years of visiting and sharing life’s joys and setbacks.

Fig. 4. My fictive mother uses a naanglo to sift wheat on the rooftop patio of her multiple story home.

In the initial months of the project, I mapped and enumerated households (N = 794) of the two most populous political sections (wards) of the village, and surveyed a random sample of 248 households for basic demographic, household history, and birth information. The number 250 was selected as a number that would result in statistically significant descriptive statistics for the population of households in the two wards.4 The data gathered in the survey provided information for choosing families for in-depth case studies according to a sampling matrix of the following characteristics: caste, socioeconomic status, education, household type (nuclear or joint), and age. This was necessary to capture the variation created by each of these categories. I had to select additional low-caste (or Dalit) families from the two wards for the case studies to compensate for the small number of them in the population. In addition, there were no low-caste families in my random sample that were in the category of moderate or high socioeconomic status.

Ultimately I selected thirty case studies (with two eventually dropping out at different stages in the interview schedule) that represented de facto joint and nuclear families of each caste and, other than the low-caste families, of middle or low socioeconomic status. Wealthy Nepali families were few and anomalous in the area, so I excluded them from the case studies. As mentioned previously, I limited my case study households to Hindu-caste Nepalis—a substantial and influential group, yet only one of many diverse cultural groups found in Nepal.5 I and my research assistant, Meena, interviewed the married women of reproductive age at each household using a semi-structured, open-ended format an average of five times over the final seven months of my initial research period, and I also had many informal conversations with them along the way.6 Originally I intended to interview husbands as well, but after discovering a few women were experiencing marital violence I abandoned the idea. The nature of my interviews could have placed women at further risk had I interviewed their husbands. Each interview ranged from thirty minutes to three hours. The topics of interviews were marriage, work, pregnancy, birth and postpartum experiences, and the role of women. The interviews took place alone in the privacy of the women’s homes, however some of the most fruitful sessions occurred spontaneously with multiple household members or neighbors present. The first two introductory rounds of household interviews were not taped, but after building rapport I used an audio recorder for the remaining three interviews in the series. Thus all quotes in the book are direct translations of women’s recorded statements, the exceptional result of a painstaking process of translation and transcription. A year later, in 2005, I returned for three months of follow-up research with the same case study families. Methods used during the 2009 and 2010 periods of research with young men are described in Chapter four, but I followed up with several of the women from the case studies during those periods as well.

The initial survey I administered in 2003 provides a snapshot of the demographics of the two wards at the beginning of the research period. The average number of years of education was seven for men and four for women. Fifty percent of the families owned their home and the other 50 percent rented. Forty percent of families owned at least one color television. Twenty-one percent owned at least one motorcycle, and 3 percent owned a car. Behind these averages, however, lies diversity. For example, portions of the community were still quite rural and uneducated. In the more urban center of the community, households ranged from joint families who had lived there for generations to unskilled laborers who were new to the area and rented single rooms. At the upper end of the wealth and education spectrum, a handful of families owned a car or had a child with a master’s degree. I excluded from the study a few anomalous, considerably wealthy families who owned car companies and international export businesses. At that time, markers of a “middle-class” family typically included a color television, a motorcycle, and possibly a computer. The children in a middle-class family typically would have been educated through the School Leaving Certificate (SLC), with young men having more education on average than young women.

Gender, Caste, and Class

All three of the categories in the title of this chapter—gender, caste, and class—are flawed in that they give the appearance of neat sociological categories that can be applied to societies all around the world. In fact, such categories need to be deconstructed and critiqued, for in different societies they are likely to be defined and lived differently. As Bina Pradhan points out in her summary of the gendered dimensions of development, the concept of gender, for example, is relatively new, and it does not exist as a single word in many languages around the world (2006). Furthermore, Seira Tamang argues that the concept of “Nepali women” only exists because of the way the development industry has construed them as falsely similar (2002).

Such definitions change over time, as well; they are subject to historical forces. Caste, for example, has often mistakenly been seen as a timeless characteristic of the Indian subcontinent. The word caste, in fact, originates in the colonial period from the Portuguese word castas, and conflates the Indian varna, the ranking system, with jaati (jaat in Nepali), the cultural and interactional system in practice. Susan Bayly argues that caste must be considered in relation to India’s social and political history, particularly the role of colonial powers and independence, and not solely as a feature of a false monolithic and static notion of Hindu ideology (1999). Furthermore, caste is practiced differently all across India. Scholars of India have engaged in a long, rich debate over what caste is and is not and its relationship to a Hindu ideology of purity and pollution versus its function of a system of power and control over people and resources (see Mines 2009 for a summary).

Such a debate has not dominated scholarship or po...