![]()

Part One

Searching for Sisterhood

![]()

1

Cleaning Race

Irish Immigrant and Southern Black Domestic Workers in the Northeast United States, 1865–1930

Danielle Phillips

In 1866 the scowling face of Mrs. McCaffraty stared out at readers of Harper’s Weekly as cartoonist Thomas Nast’s “Holy Horror of Mrs. McCaffraty” captured the unsettledness surrounding race and gender following the recent passage of the Civil Rights Act by Congress.1 In the cartoon, Mrs. McCaffraty’s round body and face are contorted with anger and her mob cap and bib apron mark her as employed in domestic service. Her basket overflows with the stuff of working-class women’s domestic labor: fish (are we to imagine that it stinks?), vegetables, and bottles. The Black woman next to her epitomizes nineteenth-century ladyhood: slender face and body, lace-trimmed dress, and bonnet with hair neatly held by a snood. Her gentle hands grasp a parasol and purse. Her casual demeanor seems uncaring or unaware of Mrs. McCaffraty’s high dudgeon. Although Black, she is the woman of careless leisure. She is Mrs. McCaffraty’s “holy horror.”2

What is striking about the image is that it illustrated a shift in the country’s attention—and anxiety—from Irish immigrant and African American men to their sisters, daughters, nieces, and wives. Since Ireland’s potato famine, native-born whites had attributed societal ills to degenerate Irish immigrant men and Black men.3 I argue that after Emancipation, African American and Irish immigrant women’s household labors as domestic workers became a medium through which the country gauged and defined racial hierarchies and undesirables. By the late nineteenth century, Mrs. McCaffraty no longer had to worry about the perception that Black women were more worthy of American citizenship than their Irish counterparts. Although African American and Irish immigrant women were concentrated in the lowest-paid women’s work by the late nineteenth century, the newcomers from Ireland would access the privileges of American citizenship before Black women.

Irish women immigrated to the United States in their greatest numbers in the mid-nineteenth century and southern Black women migrated to the North in unprecedented numbers after World War I. While the height of Irish and Black women’s movement to the urban North took place in different periods, similar circumstances fueled their migration, and their labor histories in domestic service overlapped. Both entered northeastern cities as racialized beings who had been relegated to tenant farming and household work in their hometowns. They also left the U.S. South and Ireland to escape poverty and violent social and political conflict. Of all the ethnic and racial groups of women who migrated to northern U.S. cities they were most likely to be concentrated in domestic service (except for Caribbean women).4

Overall Irish immigration declined in the late nineteenth century, yet a series of crop failures in the late 1870s and 1880s and violent conflicts between British soldiers and Irish nationalists who sought freedom from British rule fueled Irish women’s immigration to the United States until the early 1930s, when they chose Great Britain as their primary destination.5 In 1900, the U.S. Immigration Commission reported that 71 percent of Irish immigrant women in the labor force were classified as “domestic and personal workers” and 54 percent were classified as “servants and waitresses.” By 1912 and 1913, nearly 87 percent of the Irish women who had migrated to America worked in some form of private or public domestic service. And as late as 1920, Irish-born women still constituted 43 percent of white, female, foreign-born domestic servants in the United States.6

Streams of Irish and Black women from similar, but also very different contexts, flowed into the Northeast, a region fraught with its own political and socioeconomic unrest. Although native-born white northerners had boasted that the North was the pinnacle of American democracy and progress, they remained deeply ambivalent about Irish immigration, women’s rights, and Black freedom following the Civil War. They encapsulated these sentiments in portrayals of the Irish and southern newcomers as the source of the “servant problem,” or the shortage of reliable, clean, honest, and efficient household servants.7

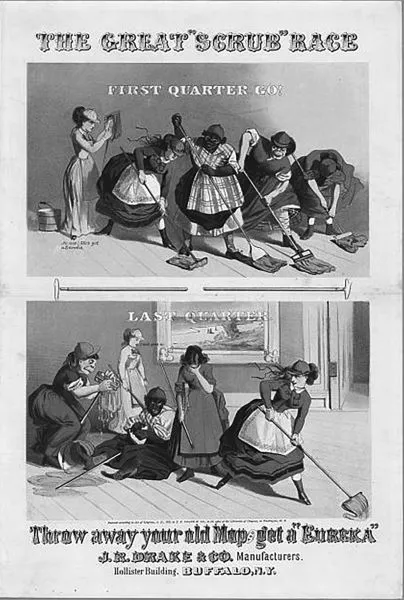

While they cleaned dirt from floors, linens, and dishes, Irish immigrant and African American women also worked at redefining ideologies of race that deemed them “dirty” and thereby undeserving of the promises of American citizenship. As Phyllis Palmer noted, “Dirtiness appears always in a constellation of the suspect qualities that, along with sexuality, immorality, laziness, and ignorance, justify social rankings of race, class, and gender.”8 As can be seen in “The Great Scrub Race” (circa 1870), progress, whiteness, intelligence, and respectable womanhood were mutually constituting categories represented in the labor of women (see figure 1.1).9

Only native-born, landowning white men were without markers of racial and gender inferiority. Unquestioned American citizens, they had the right to an education, to own property, to vote, to earn livable wages, and to live in safe and comfortable housing. Irish immigrant and African American domestic workers worked long hours in private homes to access the rights and resources of citizenship. As with work that rearranged household objects, Irish immigrant women reorganized the terms of white female respectability to include themselves. Black women’s citizenship-claiming tasks, however, were more daunting. They not only had to clear away entrenched ideologies of womanhood; they also had to eliminate ideologies of race that excluded them from the human.

The outcomes and the duration of their work could not have been more different. By the 1930s, Irish immigrant women had exited domestic service and could vote as white women. Today Irish immigrant women are engrained in the American imagination as respectable, God-fearing, hard-working matriarchs who raised their children to become responsible American citizens.10 Since slavery, ideologies of race relied on the premise that Black women were hypersexual, masculine, immoral, and permanently inferior. Hence, the work of eliminating ideologies that categorized Black women as antithetical to American citizenship persisted much longer than it did for Irish immigrant women. Black women also remained concentrated in domestic service until the latter half of the twentieth century.11 And their project is ongoing. As Melissa Harris-Perry noted in Sister Citizen, “Black women are rarely recognized as archetypal citizens.”12

The questions I explore in this chapter are the following: What do the lives and representations of Irish immigrant and southern Black women tell us about the racial projects of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries?13 What strategies did both groups of women use to redefine race as they cleaned homes and resisted labor exploitation? Because I am interested in analyzing how domestic workers shaped ideologies of race, I am exploring, as Nancy Hewitt put it, “women who sought to make sense and create order out of the upheavals of their time.”14

Rearranging Boundaries of Whiteness and Respectability

Before Ireland won its independence in 1921, the British had long declared the Irish a racial “other” to justify England’s assertion of political, religious, and economic dominance over Ireland since the twelfth century. As J. J. Lee explained, racism occurred in Ireland “where there were no observable differences” between the Irish and British.15 Protestant Irish descendants of early British settlers, the Anglo-Irish established a tenant farming labor system in the 1800s that seemed to confirm the belief that the Irish were in fact inferior to the white British. Catholic Irish families were confined to living on small tenant farms owned by Anglo-Irish landlords who demanded exorbitant rents. Irish girls had few options but to quit school at an early age and learn domestic skills including cooking, knitting, and poultry and dairy work.16 Irish women and girls also worked alongside their fathers, brothers, and husbands harvesting potatoes, vegetables, and eggs and tending to livestock for both subsistence and to sell so that they could pay their Anglo-Irish landlords.

The minimal oversight of agricultural production and the overproduction of the potato crop to meet the excessive demands of Anglo-Irish landowners facilitated fungus growth, which in turn compromised the fertility of the soil. From 1845 to 1847 a strain of bacteria spread across farms, destroying potato crops that were a source of income and personal consumption for Irish families.17 Faced with insurmountable poverty, limited options for earning a living, and virtually no political power to change their economic circumstances under British rule, approximately three million people from Ireland crossed the Atlantic Ocean to seek domestic service jobs in the United States well into the early twentieth century. Over 50 percent of the immigrants were women.18

Irish women could not have come to the United States at a better time for domestic service employers. Industrialization expanded employment options for native-born white women who had been employed as the “help” in private homes since the early nineteenth century. By the mid-nineteenth century, native-born white women had exited private household work to become housewives or work in factories. With housework experience and limited formal education, Irish-born women displaced the smaller population of free Black women in domestic service and became the largest group of servants in the urban Northeast.19

Irish immigrant women arrived in the United States as racialized beings entering a racially stigmatized occupation. Although Irish women on both sides of the Atlantic were portrayed as dirty, lazy, and domineering in contrast to their pious white Anglo-Saxon Protestant mistresses, and were concentrated in domestic service in both countries, the circumstances by which Irish women were racialized by the British in Ireland were distinct from the conditions from which the Irish “Bridget” emerged in U.S. racial discourse. The battle between Protestants and Catholics for power in the name of religion and Britain’s refusal to release Ireland and its other colonies from its control set apart the Irish from the white British race. The racialization of the Irish in the United States, by contrast, had nothing to do with land but had everything to do with political power, jobs, American citizenship, and most importantly, slavery.

The racial shift in domestic service to an Irish-dominated occupation did not diminish the negative stigma associated with it. Despite Irish immigrant women’s displacement of free Black women, the newcomers from Irel...