![]()

1

From Georgia to Maine

The GA–ME Is Afoot

On a cloudy day in the middle of May, in downtown Damascus, Virginia, the atmosphere was ripe for battle. The lightning and thunder had passed. Just a few raindrops remained, softly falling on us—and them. It was us against them, always us against them. Men and women, young and old lined the sidewalks surrounding Main Street, winding all through downtown, around the corner, and over the bridge and beyond. They were armed. We were armed. It was time. They knew it, and we knew it. In the beginning it seemed almost peaceful. Some of the local citizens of Damascus appeared on their porches as we, a mighty mob of hikers, made our way down Main Street. It wasn’t long before the first shot was fired. A water balloon. Then came the full-on attack. Water balloons, water guns, super soakers, and even the occasional water hose (see fig. 1). It was total chaos. Hikers left the parade temporarily and playfully fought with locals in their yards, all the while pelting and being pelted with weapons filled with water. Lady Mustard Seed, a twenty-six-year-old hiker from Florida, described this event as “a retreat to childhood” and “the rowdiest thing” she had ever experienced in her life up to this point. Children were screaming as they aimed water guns and sailed water balloons toward the mob of hikers. Laughter filled the air.

The town of Damascus, Virginia, with a population of 814, touts itself as the friendliest trail town on the Appalachian Trail. Each year in May approximately 10,000 people (locals, current and former long-distance hikers, hiking enthusiasts, religious organizations, gear representatives, and more) descend upon the small town for the annual Trail Days festival. Trail Days is an event that reunites Appalachian Trail hikers and celebrates their journey with food, music, gear replacement or repair, documentary film screenings, showers, medical assistance, a hiker parade and talent show, and nightly drum circles around campfires at Tent City, a large camping area approximately one mile south of town. In many ways, Trail Days is similar to a high school class reunion. For the hiker parade, held on the Saturday of the festival, long-distance hikers come together and make banners for their hiking class—say, Class of 2001—which they carry in front of them as they hike through the town of Damascus during the parade (see fig. 2).

Hobo Joe, a twenty-two-year-old hiker from Massachusetts, considered Trail Days to be “one of [his] most memorable experiences.” He remarked: “Once you’re out here you really belong to this group of people. It’s very exclusive in that way.” Many hikers echo Hobo Joe’s sentiments about Trail Days as a “highlight” of the Appalachian Trail experience, which is why many hikers, past and present, come back year after year to relive those experiences and renew friendships.

The stories of community and belonging as told by Hobo Joe represent a familiar pattern for many long-distance hikers on the Appalachian Trail. Trail Days is but one of many events or places along the Appalachian Trail that allow hikers to come together, creating a unique bond among members of this leisure subculture. For hikers like Drifter, a forty-four-year-old repeat thru-hiker from New Hampshire, the lifelong friendships he has made over the eleven years of hiking the Appalachian Trail and the shared experiences that he believes he can only have on the Appalachian Trail are what continue to bring him back to the AT, time and again.

In his 1958 book The Dharma Bums, beatnik Jack Kerouac wrote, “Think what a great world revolution will take place when . . . [there are] millions of guys all over the world with rucksacks on their backs tramping around the back country.” The numbers have not quite reached “millions,” but thousands of men and women, old and young, have developed an interest in long-distance hiking. Compared to the relatively short-term activity of day hiking or overnight hiking, long-distance hiking (or backpacking) requires multiple days and nights on a trail while carrying camping gear, food, and shelter (although sometimes shelters are provided in the form of three-wall lean-tos or four-wall huts).

Long-distance hiking did not begin to grow in popularity until 1970, driven in part by the release of Ed Garvey’s book Appalachian Hiker: Adventure of a Lifetime. Between 1936 and 1969, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy recorded only fifty-nine completed hikes of the AT. In 1970, ten people, including Garvey, were recognized as “2,000-milers”—a term used to identify a growing group of hikers who set out to hike the entire length of the Appalachian Trail. In the decades that followed, the number of 2,000-milers increased dramatically, particularly during times of economic recession. In 2006 and 2007, two years before the most recent recession, there were 525 people recognized each year as 2,000-milers. Since the Great Recession, there has been a steady increase of approximately 40 to 90 additional 2,000-milers per year. Perhaps some individuals are looking to hike the Appalachian Trail as an escape from urban living and the fatigue and stress associated with it as they search for emotional or spiritual rescue related to job loss or limited job opportunities.

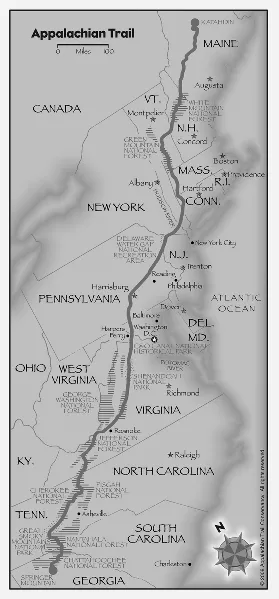

On August 14, 2012, America’s 2,181-mile-long Appalachian Trail celebrated the seventy-fifth anniversary of its completion as the longest hiking-only footpath in the world. Often referred to as the longest and skinniest national park, the Appalachian Trail crosses fourteen states and more than sixty federal, state, and local parks and forests (see fig. 3). Marking the official route of this congressionally recognized National Scenic Trail are white paint blazes, two-inch-by-six-inch vertical rectangles, found in both directions and painted on everything from rocks and trees to signs, bridges, posts, or other objects approximately one-tenth of a mile apart.

The United States is home to eleven congressionally recognized scenic trails, nineteen historic trails, and over a thousand recreation trails. Other long-distance trails in the English-speaking world include fifteen national trails in England and Wales, and another four in Scotland. In the end, I chose the Appalachian Trail as my research site because it is arguably the most social and most frequented long-distance hiking trail. Overall, since 1936, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy has recorded slightly more than 12,000 completed hikes made by thru-hikers (those completing the entire trail in one continuous journey) and section hikers (those completing the trail in large sections over a period of time). Of this number, a little more than two hundred hikers have thru-hiked the Appalachian Trail more than once.

Of those trails that make up the Triple Crown of hiking trails (that is, the Appalachian Trail, the Pacific Crest Trail, and the Continental Divide Trail), the Appalachian Trail is by far the most internationally famous and most popular. According to the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, people from all over the world—Australia, Austria, the Bahamas, Belgium, Canada, Chile, the Czech Republic, Denmark, England, Finland, France, Germany, Holland, India, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Morocco, New Zealand, Norway, the Philippines, Romania, Scotland, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Wales—have reported hiking the Appalachian Trail. This phenomenon maybe due in part to the 1998 publication of travel writer Bill Bryson’s bestselling book, A Walk in the Woods: Rediscovering America on the Appalachian Trail, wherein he humorously describes his attempt to reconnect with his homeland by thru-hiking the Appalachian Trail with his out-of-shape friend, Katz. This particular cultural representation of the trail by Bryson is reported by hikers and nonhikers alike, in the United States and abroad, as their first introduction to the Appalachian Trail. The influence Bryson has had on people’s decisions to thru-hike the Appalachian Trail is likely to increase with the release of a movie based on his book, starring Robert Redford as Bryson and Nick Nolte as his buddy Katz. The film premiered during the 2015 Sundance Film Festival and was released in September 2015.

Unlike Drifter, the repeat thru-hiker from New Hampshire introduced earlier, the typical long-distance hiker is stepping onto the Appalachian Trail for the first time and has either recently graduated from high school or college or just retired. Most, however, are like Drifter in that long-distance hikers are predominantly single, white, male, educated, and come from working- and middle-class American families. Many admit to choosing to hike the Appalachian Trail because it is the most social and most well-known long-distance hiking trail in the United States compared to its cousins, the Pacific Crest and Continental Divide Trails.

Like most hikers, including Hobo Joe, Drifter, and Lady Mustard Seed, I was introduced to the Appalachian Trail by a friend who had hiked all of it, except Maine anyway. During summer 1999, I hiked approximately 350 miles in just over a month, from the Delaware Water Gap on the Pennsylvania–New Jersey border to Manchester Center, Vermont. Before this time I had been unaware of the Appalachian Trail, or its iconic status, and had never been long-distance hiking. This is not uncommon for a majority of long-distance hikers. When I returned to hike another portion of the trail in 2005, I had no idea that it would be the beginnings of a larger research project. I knew from my experiences in 1999 that the Appalachian Trail was a special place, a storied place. There was a unique community that formed among hikers as they made their way from Springer Mountain in Georgia to Mount Katahdin in Maine. So this time, and again in summer 2007, I figured that while I was out there hiking I might as well get to know the hiking community better.

Because I could talk the talk and walk the walk, it was not difficult for me to gain entry and become part of the long-distance hiking community on the Appalachian Trail. Everyone I approached was more than willing to speak with me about their trail experiences and relationships with fellow hikers. In fact, no one I approached declined to be interviewed. The majority of long-distance hikers I spoke with identified themselves as thru-hikers, meaning their intentions were to thru-hike the trail over the course of the next few months. I do not know how many of them actually made it to Katahdin. Most began hiking the trail in mid- to late March or early April. Although April Fool’s Day is traditionally the first day for starting a northbound thru-hike, a few long-distance hikers started as early as February, which I am finding to be increasingly common.

Given that nearly four million people will set foot on the trail each year, the long-distance hikers I had the opportunity to speak with are not representative of all who hike or come to experience the Appalachian Trail. When I searched Amazon and Google, I found more than thirty-five memoirs in which hikers recounted their experiences of long-distance hiking, and that’s only on the Appalachian Trail. Most recently, Cheryl Strayed chronicled her 1995 solo hike on the Pacific Crest Trail in Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail (2012). Her memoir received rave reviews and became the basis for a film of the same title starring Oscar-winning actress Reese Witherspoon. The film was released in December 2014 in select locations. The attention Strayed’s book, and now movie, has brought to the growing activity of long-distance hiking has been referred to by media outlets as the “Wild effect,” as hundreds of women hit the PCT, inspired to follow in Strayed’s footsteps.

Although there have been quite a number of hiking memoirs published, this ethnographic project, in which I explore the long-distance hiking community on the Appalachian Trail, is the first in-depth research project of its kind. Recognizing that subcultures are best conceptualized and understood as products of social interaction, I focus on social relationships and social practices among members of the long-distance hiking community. My approach reveals that beyond exploring the social self, it is vitally important to examine the place-situated self. Environmental sociologist Kai Erikson (1994) stated in his studies of trauma and the human experience of modern disasters that personal investment in a place (home, for example) is not simply an expression of one’s preferences or tastes but rather an expression of one’s personality, a part of the self. Within the discipline of sociology, when speaking of the development of the self, sociologists generally focus on a socially situated self that is constructed in relation to significant others. Largely missing from this body of work is the notion that we are also place-situated beings, forming identities in relation to significant places, not solely from attachment to others.

The Appalachian Trail has been imbued with multiple meanings since the idea of the trail itself was first introduced in 1921 by Benton MacKaye. MacKaye’s vision of the Appalachian Trail project was not the long-distance hiking trail known today but rather a practical vision for wilderness conservation in the Appalachian region. MacKaye believed that a series of recreational camps and community life, compared to modern society, would replace the dull, routine existence of the working class and become a sanctuary and refuge from the commercialism of everyday life (MacKaye 1921; Minteer 2001). In other words, MacKaye envisioned a trail that would become an alternative to urbanization and development rather than an adjustment to it (Foresta 1987). According to Ronald Foresta (1987), MacKaye’s biggest problem was that his idea and his initial vision of the project came too late—the social structure and class outlook in the United States had changed. After 1918, there was no longer concern about improving life for the working class through social reform but rather how to accommodate the reality of industrial capitalism (Foresta 1987; Minteer 2001). There was no longer a direct attack on modern industrial society because industry created wealth for many sectors of society and increased the range of consumption opportunities for citizens, including the consumption of leisure activities (Foresta 1987).

Another reason the Appalachian Trail project failed to be an instrument of social reform for the urban working class was that MacKaye and early reformers did not provide the leadership necessary for such a project (Foresta 1987; Minteer 2001). Initially a cooperative venture guided by social reformers, the Appalachian Trail project fell into the hands of professionals guided by public land managers, all of whom were encouraged by industry and benefitted from the opportunities an emerging industrial society had to offer (Foresta 1987). Headed by Myron Avery, this new leadership established the first Appalachian Trail Conference (renamed the Appalachian Trail Conservancy in 2005). The primary focus of the ATC was on trail construction and design, and coordinating the volunteer activities of local hiking clubs (Foresta 1987). Avery and his associates were typical of those who became active in the Appalachian Trail project after MacKaye. They were young, educated professionals—public land managers, foresters, lawyers, professors, physicians, editors, and scientists—whose activities and interests in the Appalachian Trail were separate from their vocations, a pattern common among middle- and upper-class Americans of that era. Since most of the trail builders were professionals and had secure jobs, they were not as concerned with the social ills of the day but instead viewed nature as a temporary escape from society. They believed the Appalachian Trail would allow individuals an opportunity to enjoy the material benefits of the city as well as the spiritual and physical conditioning of the great outdoors (Foresta 1987).

Today, the Appalachian Trail is a primitive environment in which long-distance hikers can become temporarily separated from modern society. Moreover, certain features associated with long-distance hiking help promote a unique place-situated identity for members of the hiking community. Some of those conditions are the geographical, physical, and social isolation from mainstream society; continuous contact with other long-distance hikers, directly or indirectly; the exceptional difficulty, danger, and variability of the trail; and the necessity of being and living on the trail on a daily basis for an extended period of time. Additionally, places and events along the Appalachian Trail, such as Trail Days mentioned at the beginning of the chapter, provide opportunities that encourage feelings of community and camaraderie among hikers. When I asked Swinging Jane, a sixty-three-year-old thru-hiker from Ohio, what her highest point had been so far, she mentioned trail towns or other places on the trail itself. For her, “the Damascus area was a high point, and Silar Bald was a high point. . . . The Mount Rogers experience was something that I’ll eventually go back and do again. Grayson Highlands and seeing the ponies. I think all of those were high points.” As Spirit, a fifty-seven-year-old section hiker from Tennessee, put it, “You may not be religious but you are going to go through something on this trail.”

For most long-distance hikers, like Swinging Jane, Spirit, and others introduced earlier, the Appalachian Trail represents a meaningful place whose power is unfolded in the stories long-distance hikers share about their trail experiences. This study is the first of its kind to adopt a holistic approach to investigating the construction of a place-based identity. Although my sample is not necessarily representative of the entire long-distance hiking community, my focus on long-distance hikers on the Appalachian Trail reveals the presence of a multilayered leisure subculture. As part of this study, I compiled basic statistics about age, race, class, gender, and education; I was, however, less interested in quantifiable conclusions than in the narrative of the lived experiences of long-distance hikers.

Doing ethnographic fieldwork and conducting in-depth interviews with long-distance hikers provided me an opportunity to give voice to a group of hikers who have largely been ignored in leisure and recreation studies. While I am familiar with this body of research, I will spare the reader an extended discussion and simply say that most research on hiking in the area of...