![]()

1

(De)Mystifying Tricks

The Wonder Response and the Emergence of the Cinema

All incitation to inquiry is born of the novel, the uncommon, and the imperfectly understood.

—Ernst Mach, “The Propensity toward the Marvelous”

An early scene in Ingmar Bergman’s film The Magician (Ansiktet, 1958) foregrounds a curious and distinctive dimension of modern stage magic: the impulse to investigate the techniques behind magicians’ tricks. The film centers on an itinerant magic troupe known as Vogler’s Magnetic Health Theater, which has been stopped by the police on the outskirts of nineteenth-century Stockholm and escorted to the house of the city magistrate. The motivation for the troupe’s arrest at the border is the deeply troubling question of whether the leading magician, Vogler (Max von Sydow), possesses supernatural powers or whether his magic is the result of puzzling but rationally explicable tricks only cloaked in the guise of the supernatural. The uncertainty stems from the fact that Vogler is rumored to be capable of hypnotizing spectators and controlling their minds, a claim that has also been advanced for the cinema. The safe passage of the troupe ultimately hinges on the possibility of explaining this Mind Control trick, because a completely rational answer for “how it’s done” will position Vogler’s illusions on the benevolent side of wonder rather than on the dark, potentially malevolent side of the inexplicable.

The centrality of rationalism and explanation in trickery surfaces when Vogler’s assistant and manager, Tubal (Åke Fridell), urges the cohort to be careful when speaking to the city’s officials. Tubal is particularly concerned to caution Vogler’s grandmother (Naima Wifstrand), a supposed witch whose mysterious antics have caused serious problems with audiences in the past, some of which put the troupe in mortal danger. Chiding the old lady for apparently exercising occult powers at previous performances, which it is suggested involved conjuring ghosts, turning tables (in the Spiritualist tradition), and creating magical potions, Tubal claims: “Granny’s tricks are out of date. They’re not amusing, as they can’t be explained.” Although his remark is delivered lightly, the implied problem with this “old” magic is quite profound. By skirting the possibility of demystification altogether, Granny’s “tricks” might expose the limits of spectators’ capacities for explaining wondrous phenomena, as well as spectators’ powerlessness over their perceptions. Losing control in this way would undermine the playfulness that makes magicians’ tricks so pleasurable; it would also compromise a sense of reality as something that can be mastered through vision and rational thought.

The Magician positions Vogler’s magic somewhere between Granny’s old magic and a kind of harmless and superficial trickery. The story is organized around a rigorous investigation by a scientist, the Royal Medical Adviser, Vergerus (Gunnar Björnstrand), into the techniques behind Vogler’s illusions. Vergerus embodies the unwavering skepticism one would expect of a man of science confronted with rumors of supernatural powers. By means of questioning and close observation, he tries to determine how the Mind Control trick works. The scientist’s goal is to expose the magician as a fraud because, as Vergerus explains, if Vogler’s tricks were truly inexplicable, the modern scientific enterprise would crumble, along with Vergerus’s faith that “everything can be explained.”

Early in the interrogation, Vogler’s wife (Ingrid Thulin), disguised as his apprentice, Mr. Aman, quickly disavows supernaturalism and claims that Vogler’s tricks can be traced to the clever but harmless use of “devices, mirrors, and projections.” Vergerus is not interested in what he considers to be the obviously dubious “hocus pocus” of magic. What unsettles him is the very possibility that the illusions he witnesses cannot be explained. For the duration of the film, the troupe is detained at the magistrate’s house, where they are forced to perform their act under Vergerus’s scrutiny. However, try as he might Vergerus cannot find a way to explain the Mind Control trick, and the scientific investigation of Vogler’s tricks is ultimately inconclusive. Neither Vergerus nor the filmgoer ever finds out whether or not the magician possesses supernatural powers.

By pitting Vogler against Vergerus, The Magician stages a game of perception that has animated the experience of wondering at magicians’ tricks for centuries. This game is played by what I call the “magic professor” and the “spectator detective,” competing figures whose respective goals are to conceal and to detect how a trick works. In The Magician, for example, Vergerus (the detective) ultimately loses the game to Vogler (the professor) who manages to thwart the expert’s attempts at discovering the magician’s secret techniques. In the history of secular stage magic, the interplay between concealment and detection has taken shape largely as a game because its object is not so much deceit as it is a kind of playing with the boundaries between authenticity and fakery, reality and unreality.

At least since the eighteenth century, audiences have taken great pleasure in competing with the virtuosity of magicians who perfected a form of self-conscious trickery that was premised simultaneously on astonishment and the possibility of demystification. By gesturing at once symbolically to the supernatural and technically to the explanatory powers of science and reason, “modern” magicians made the experience of wonder inseparable from an impulse toward detection and knowledge. The wondrous “How did the magician do it?” was wedded to the purposive search for a satisfactory answer.

The pleasure of this game, to be precise, is not necessarily in the discovery of “how it’s done” but in the act of playing the game, that is, the experience of trying and almost always failing to thwart the magician’s tricks. The affinity between intellectual curiosity and such a self-conscious form of trickery challenges a pervasive view of stage magic as simply a forum for displaying deluding or amusing spectacles. With a resemblance to the popular science demonstrations and philosophical toys that proliferated in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, stage magic developed not as a voyage beyond knowledge into the inexplicable but as an occasion for contemplating and learning about the obscure and the unknown.

Stage magic’s dramatic affinity for the extraordinary, the unknown, and the supernatural was thus largely mediated by the question that lay at the heart of Tubal’s critique of Granny: What is the attraction of a trick that can be explained rationally, as opposed to one that invokes the supernatural and thus refuses reason altogether? As we will see, this question was central to the dominant themes, regimes of belief, and scientific-technological innovations that shaped and distinguished the culture of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century stage magic as a complex form of educational entertainment. It is also central to our familiar experience of the cinema as a device of wonder, that is, as a kind of “mechanical magician” whose techniques of trickery are at work behind everything from the illusion of movement itself to the wonders of computer-generated imagery (CGI). In fact, the pursuit and discovery of knowledge through illusions are at the heart of the wonder associated with beholding the effects of the innovative techniques and technologies that have changed (and continue to change) how we see and experience the cinema.

BETWEEN WITCHCRAFT AND SCIENCE

By setting The Magician in the nineteenth century, Bergman invokes a very specific tradition of magical practices that resonated profoundly with the emergence of the cinema in the 1890s. Vergerus explains that Vogler’s magic is of “scientific interest” because his tricks appear to waver between mesmerism and the occult, on the one hand, and science and entertainment, on the other. Explaining the magician’s tricks would affirm the power of science over the irrational. But Vergerus has no doubt that he will succeed in this, and the investigation becomes an opportunity to pit his skills as a scientist against Vogler’s skills as a magician. Throughout the film, moreover, Vogler is referred to interchangeably as a magician, a conjuror, a fraud, a doctor, and a scientist, and his illusions are claimed to be the apparently supernatural effects of otherwise simple “devices, mirrors, and projections.” Early in the film, for example, Vogler is accused of harboring occult powers because he is rumored to be able to “evoke stimulating and terrible visions” during his performances. It is later revealed, however, that the magician has been touring with a magic lantern, a mechanical device of wonder that has become a centerpiece in the shared histories of magic, science, and the field of proto-cinema.

As a dialectical and highly ambiguous figure, Vogler represents a historical opposition between old (occult) and new (secular) magics that was fueled by two developments: modern stage magic’s emergence within the context of Enlightenment critiques of the occult, and nineteenth-century proclamations of the death of the supernatural at the hands of modern science. In his introduction to a seminal fin-de-siècle treatise on magical practice Henry Ridgely Evans announced, “Science has laughed away sorcery, witchcraft, and necromancy.”1 What was left of magic, once the laughter had quieted, was a form of trickery performed by magicians whose coiled relationship with science, spectacle, and investigation remains a largely unexcavated site of media-related inquiry (partly because modern magic is often treated merely as a source of delightful entertainment, partly because of magic’s own principles of secrecy, misinformation, and deceit). Stage magic’s profound cultural relevance as a project of the Enlightenment is also usually upstaged by the misleadingly showy figure of the magician, whose entertaining tricks simply follow suit.

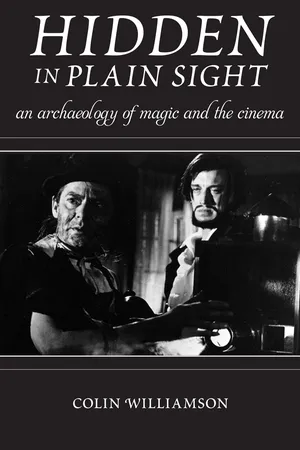

FIGURE 2. Vogler the magician (in the background) operating a magic lantern while the “ghost” of an actor (in the foreground) marvels at the device’s projected image. Reproduced from The Magician (Ansiktet), directed by Ingmar Bergman (Svensk Filmindustri, 1958), DVD.

But if we take seriously the idea that trickery is as much about entertainment and deception as it is about the possibility of investigation and discovery, then we can begin to see the magician’s affinities with the cinema in a new light. Prior to the 1890s, modern magic was widely presented as a harbinger of progress because it appealed to modern science rather than religion and superstition.2 In the nineteenth century, stage magicians like Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, John Henry Anderson, John Nevil Maskelyne, and George Albert Cooke turned away from the realm of fear, beguilement, and the supernatural and reorganized magic around the performance of “miracles” in the name of scientific discovery. With a resemblance to early cinema’s middle-class appeal as a safeguard against the social deviance and immorality associated with nickelodeons, modern magicians, particularly under the influence of the preeminent French mechanic, inventor, and prestidigitator Robert-Houdin, sought “to establish the conjuror as a ‘respectable’ kind of entertainer.”3

As the investigation of Vogler’s tricks in The Magician suggests, the question in the nineteenth century was whether the illusions of sorcery, witchcraft, and necromancy could be made acceptable as forms of rational theatrical entertainment for polite society. Secular stage magic was thus conceived as an intricate critique of the supernatural. Against the aesthetics and rhetoric of occult séances, for example, Robert-Houdin offered his audiences magic performances that were stripped down and scientific in tone and appearance. When he debuted his tricks at the Soirées fantastiques in a small theater at the Parisian Palais-Royal in 1845, Robert-Houdin used no atmospheric objects to cultivate an air of the supernatural, no full-length tablecloths to blatantly conceal the operations of sleight-of-hand tricks. He also opted for the evening dress of polite society and engaged his audiences with plain speech that appealed to the intellect rather than to credulity. His performances were presented as “experiments,” which he claimed were “divested of all charlatanism, and possess[ed] no other resources than those offered by skillful manipulation, and the influence of illusions.”4

This pursuit of respectability was more than a superficial reform of the presentation of illusions, however. According to Simon During, “Robert-Houdin negated the triviality and cultural nullity of magic by bringing to the stage the prestige of the inventor and scientist.”5 The Soirées fantastiques featured not only performances of mysterious levitations and disappearances but also trick automata, electromagnetism, and optical conjuring, or the use of mirrors to render opaque objects translucent or invisible. While performing these illusions, Robert-Houdin often assumed the role of a lecturer or demonstrator by accompanying his tricks with pseudo-scientific patter and plausible (albeit partial) explanations.

The proliferation of books on the history and theory of magic prior to and during the emergence of the cinema is dominated by a preoccupation with mapping these distinctions between old and new magics. Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century accounts of modern magic (including those by magicians like Robert-Houdin, Maskelyne, and David Devant) defined the function of the “new” art as mediating an opposition, Janus-like, between the wonders of modern science and the deceptions of “primitive,” “savage,” or “pre-scientific” forms of magic. Scientific magic was noble, forward-reaching, and good; “savage” magic was antiquated, corrupting, and debased.

Charles Musser makes a similar distinction in charting what he calls the “history of screen practice,” which locates the cinema in a broader history of the magic lantern and its rationalist uses. According to Musser, this history begins with Athanasius Kircher’s treatise on catoptrics, dioptrics, and astronomy, Ars magna lucis et umbrae (1646), in which the magic lantern’s seventeenth-century use is highlighted as being different from an “old” set of cultural practices that promoted the device as a supernatural medium and a source of fear. With Kircher, whose status as a “natural” magician makes him (like Vogler) more of a transitional or intermediary figure than a “modern” magician, the magic lantern becomes central to an emerging mode of exhibition that privileges enchantment as well as enlightenment and demystification.

In Kircher’s approach to studying and teaching the science of optics, the magic lantern figured largely as an aid to popular scientific demonstrations and was visibly integrated as part of his lecture format. But, in the history of screen practice, the magic lantern was not simply put on display as a technology to be admired and observed for the scientific principles it could demonstrate and the entertaining spectacles it could produce. According to Musser, “The revelation of the techni...