1

The Graduate School Years

New Demographics, Old Thinking

The graduate student and postdoc years are the proving ground for future academics. Many students enter with clear plans to become professors, but end up changing their minds. There are many reasons to reject an academic career, but family considerations—marriage and children—are most prominent for women and a serious concern for men as well. How concerns about family affect these young scholars’ decisions is complex. Some students lack the role models that might otherwise demonstrate that work-family balance is possible in academia. For others, encountering intense professional hostility after having a baby weakens their commitment to an academic career. Sometimes marriage presents a barrier to developing two careers. The scientific disciplines, which foster a nonstop competitive race to the top, offer a particular challenge. The academy has recently focused attention on the work-family concerns of faculty, but it has largely ignored graduate students and postdoctoral fellows. This chapter considers how these young scholars confront family issues, and how a few universities are beginning to remake the academic workplace in order to retain graduate students and postdocs in the career pipeline.

The New Face of Graduate Students

The new generation of doctoral students is different in many ways from that of just thirty or forty years ago. Academia was once composed largely of men in traditional single-earner families. Today, men and women fill the doctoral student ranks in nearly equal numbers, and most will experience both the benefits and the challenges of living in dual-earner households. This generation also has different expectations and values from previous ones; most notably, the desire for flexibility and balance between their careers and their other goals. But changes to the structure and culture of academia have not kept pace with this major shift in students’ priorities. The outdated notion of the “ideal worker” prevails, including in a de facto requirement for sole devotion to the academy and a linear, lockstep career trajectory that permits no interruptions. Senior faculty and administration, still largely men, are not role models for the new generation of scholars when it comes to demonstrating the work-family balance and flexibility that these students desire.1

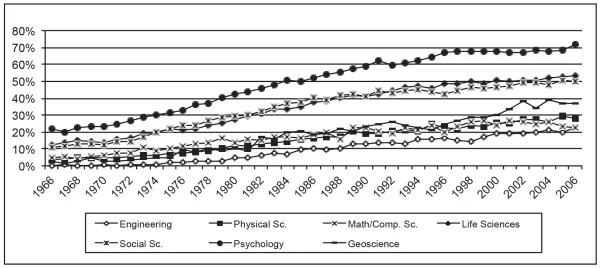

The most significant change in the graduate student body is that women are now as numerous as men. Indeed, gender parity in graduate education is one of the remarkable accomplishments of the past forty years. In 1966, just 12 percent of all American doctorates were awarded to women.2 By 2008 that number had soared to over 50 percent.3 There have also been impressive gains for minority students, particularly minority women, but they still are by no means proportionally represented. Moreover, the gender balance remains more uneven in some disciplines than in others. In 2008, women received only 28 percent of the doctorates awarded in the traditionally male-dominated physical sciences, including computer science and math, and just 22 percent of those awarded in engineering.4 Although these are lower proportions than seen today in the more human-centric disciplines such as biology and psychology, they nonetheless represent extraordinary progress. As figure 1.1 shows, over the past four decades the proportion of women Ph.D. recipients has increased more than a hundredfold in engineering, twelvefold in the geosciences, and sevenfold in the physical sciences. Since these trends appear unabated and women are outperforming men at the baccalaureate and master’s levels, it seems reasonable to assume that further gains will occur.5

In addition to being notably more female than they were three decades ago, today’s doctoral students are a bit older: The median male Ph.D. recipient is now thirty-two and the median female doctorate recipient is now thirty-three.6 Students in the natural and physical sciences often finish their Ph.D. at a somewhat younger age but are increasingly likely to spend time as postdoctoral fellows.7 They may hold these positions for years before acquiring a tenure-track job. Most women faculty will therefore be at or near the end of their childbearing years by the time they achieve tenure. Postponing a family until tenure, the old wisdom offered to women graduate students, remains bad advice for purely biological reasons.8 But what about having children during graduate school, when women are more fertile? As we shall see, few students view this as a good option.

A Bad Reputation

Work-family balance weighs heavily on the minds of graduate students as they ponder their careers; in our landmark 2006–2007 survey of about eight thousand doctoral students at the University of California, 84 percent of women and 74 percent of men registered the family friendliness of their future workplace as a concern. Yet more than 70 percent of women and over half of all men doctoral students surveyed consider faculty careers at research universities not friendly to family life.9

Most doctoral students begin their careers with the same hopes and dreams as generations before them: they want to become professors. About two-thirds of doctoral students at the University of California said this was their objective when they began graduate school. The majority aspired to faculty positions at major research universities, and most of the others to jobs at four-year teaching colleges. But graduate school frequently causes them to change their minds about careers at research universities. About 30 percent of the women and 20 percent of the men we surveyed turn away from their goal of becoming a professor at a major research university, and instead intend to pursue careers in nonacademic settings.10

Men and women offer somewhat different explanations for their apprehensions about academic careers. Both men and women are more likely to report dissatisfaction with the unrelenting work hours. As one male student at the University of California complained, “[I’m] fed up with the narrow-mindedness of supposedly intelligent people who are largely workaholic and expect others to be so as well.”11 Women, however, are especially likely to focus on family concerns. “I could not have come to graduate school more motivated to be a research-oriented professor,” one female student related. “Now I feel that can only be a career possibility if I am willing to sacrifice having children.”12

Our one-on-one interviews with doctoral students yielded similar findings. Carolyn, a fifth-year Ph.D. student in engineering at a major research university and mother of a three-month-old son, faced a series of challenges when she considered starting a family during her graduate studies.13

Carolyn grew up in a working-class neighborhood in Texas. Neither of her parents attended college, but her father worked with engineers at a power plant, and he strongly encouraged Carolyn’s interest in an engineering career. She was an outstanding student in both science and the liberal arts and earned a double degree, a BA and a BS, from the University of Texas. Soon after graduation Carolyn married her high school sweetheart. She planned to work for four or five years, then start a family.

But Carolyn was soon drawn back to academia. “I realized I could do much more real research with a Ph.D.,” she related. Carolyn’s husband, Ken, was already pursuing a doctorate, so she waited her turn and supported his studies. She began her own graduate program at the age of twenty-seven, but realized that the time commitment and work environment probably wouldn’t allow for children in the near future. “We were already very ready to have a family, but I didn’t see how we could make it work,” she said. Only 20 percent of the students in Carolyn’s department were women, and none had ever had a baby. The demands of graduate school had upended Carolyn and Ken’s plans, and they abandoned their intention to start a family anytime soon.

Doctoral Student Parents

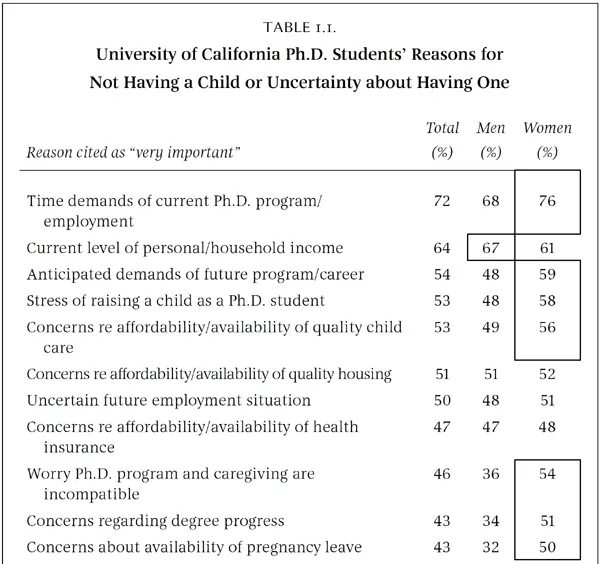

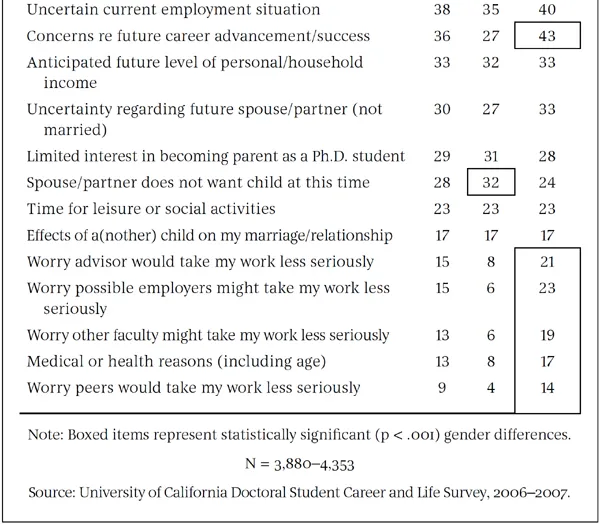

According to our survey of University of California Ph.D. students, only 14 percent of men and 12 percent of women are parents.14 Yet over two-thirds of the women claim that between twenty-eight and thirty-four would be the optimal age to have a first child.15 Why do most women avoid having children during graduate school? After all, it’s a time of flexible schedules and the possibility of a community with which to share the experience of parenting. The most common reason provided by our University of California respondents is the workload, as table 1.1 shows. Sixty-eight percent of male students and 76 percent of female students cite graduate school work requirements as the most important reason to hold off on children; women are also far more likely than men to believe that graduate school and parenthood are fundamentally incompatible.

It is worth noting that women are more likely than men to put off having children for the same reasons that one of the authors of this book, Mary Ann Mason, did more than thirty years ago: they fear that they will not be taken seriously and that their professors and future employers will disapprove. One student at the University of California commented on her department’s attitude toward pregnant students: “There is a pervasive attitude that the female graduate student in question must now prove to the faculty that she is capable of completing her degree, even when prior to the pregnancy there were absolutely no doubts about her capabilities and ambition.” According to table 1.1, two to three times more women than men were concerned that having a child would be negatively perceived by their professors or future employers.

The bench sciences offer additional challenges for student parents, particularly mothers. Would-be scientists have far less flexible schedules than do graduate students in the humanities and many of the social sciences. Most of the bench sciences require long hours spent in campus labs. Moreover, the competitive race to achieve scientific breakthroughs and prove oneself offers little respite for childbirth or childrearing.16 This is reflected in the blog of a postdoc at the Washington University School of Medicine, Academic Aspirations: “In science especially, research fields move very quickly. The maternity leave time could be just enough for you to be scooped and lose months or years’ worth of work. It’s a frustrating thing to think about.”17

None of this is a secret to female scientists. Jennifer, a neuroscience postdoc, had her first child soon after finishing her Ph.D. “I don’t think I’ll ever be able to do a tenure-track job, and people were very upfront with me about that when I had my child. Looking around me, I see that people are completely shut out of positions because of family.”18 Not surprisingly, the message is different for men. Men who marry and have children are considered more mature and better able to handle their work, while women are considered less serious.19 The assumption is that women with children do not get work done—and with limited grant funding available, research positions should go to those who have the most promising futures. Marriage, as we will see in the following chapter, limits a woman’s flexibility to seek the best jobs, and pregnancy anytime prior to tenure is seen as evidence that she is not seriously dedicated to her career. And the density of men, as in many professions, reinforces the male status quo. At present, too many students agree with one UC woman student’s appraisal: “Don’t get a Ph.D.! Just don’t do it: there are so many other things in life that you could do for a living that are as intellectually challenging, pay more, and where women having children is not a big deal. Academia is stuck in the 1970s at best on this issue.”

Financial Constraints

The graduate student years are typically a period of limited incomes and modest lifestyles—the years of the Ramen noodle diet—and finances are clearly a concern for student couples considering parenthood. Raising a child brings many new expenses: health care costs, child care, housing, diapers, and clothing. All told, American parents now spend more than eleven thousand dollars a year on expenses for a baby or toddler.20 In our survey of Ph...