![]()

1

Serials, Melodrama, and Play

Why Study Serials?

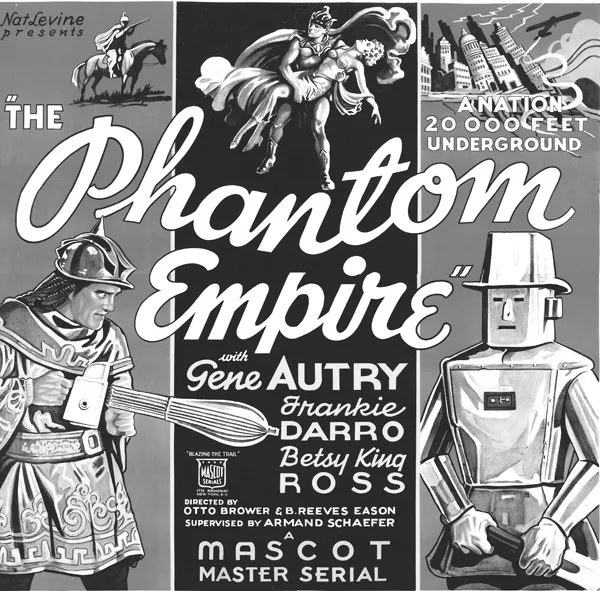

The opening chapter of The Phantom Empire (Brower and Eason, 1935) boils with cockeyed vitality. Gene Autry’s “gang” robs a stagecoach of musical instruments. Back at their “Radio Ranch” they launch into the speedy patter song “Uncle Noah’s Ark,” part of their weekly broadcast. Frankie and Betsy (Frankie Darro and Betsy King Ross), the young “president and vice-president of the National Thunder Riders Club,” step to the microphone and invite the radio audience to join their organization. To explain its name, the two kids introduce a flashback in which legions of caped and helmeted horsemen bolt across the landscape. Frankie, still within the flashback, looks directly into the camera and announces: “That’s how we came to call our club the Thunder Riders.” Without delay, Autry narrates the next installment of the Thunder Riders’ Radio Play, enacted before the camera by members of his band. Bandits batter at a cabin door held tight only by the brave homesteader’s arm in place of the bar lock. Autry announces, “It seems but a moment before his bruised and tired arm would break,” and then asks: “Will the Thunder Riders get there in time?”

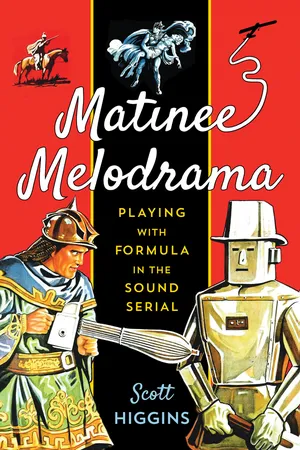

All of this is mere prelude to the introduction of the villainous Professor Beetson (Frank Glendon), who has his sights set on the lode of radium hidden beneath Radio Ranch, and the spectacular revelation of the (miniature) underground “scientific city” of Murania, ruled by Queen Tika (Dorothy Christy), who monitors the primitive surface civilization on her giant television. In less than ten minutes, we are asked to enjoy the show, encouraged to acknowledge its silliness, and invited to play in and with this world. Bizarre juxtapositions, direct address, suspenseful interruption, and the mandate to employ any cheaply available means for a thrill are the serial’s indispensable resources. The Phantom Empire is part of a rich tradition that thrived at the very margins of studio-era Hollywood: a tradition of creative ridiculousness, visual brio, and distinctively outlandish storytelling (see figure 1).

The founding premise of this book is that sound serials are intrinsically interesting; they demand our film-historical attention simply because they exist. These films, over two hundred of which were produced between 1930 and 1956, also merit study because they have been influential and because they are relevant to contemporary media scholarship. Two generations after the last American serial was produced, they continue to inspire dedicated fan communities and to reverberate in our media culture, from the costumed attendees of Comic-Con to contemporary action film franchises. Researchers in the burgeoning field of seriality studies consider continuing narrative “a defining feature of popular aesthetics.”1 In comparison to work on television, comics, and silent film, however, academics have been surprisingly slow to take up the sound serial. The present volume addresses the serial’s influence and participates in scholarly discourse, but it originates in the observation that these films are deeply engaging, powerfully entertaining, and infinitely watchable.

They are also quick, dirty, and unabashedly formulaic. By the standards of most feature films, sound serials can appear cheaply melodramatic and devoid of psychology, subtlety, or elegance. But this is not their failing. The serial’s strengths aren’t the classical feature’s dramatic unity, coherence, or even continuity but strongly drawn situations, starkly physical characters, and predictable, inhabitable worlds. Indeed, the case of sound serials helps demonstrate how selective and narrow our conception of studio-era cinema might be. Our aim here is to meet these films on their own terms by dwelling within the form. Sound serials deliver direct, visceral, and extended narrative experiences that reassure us in the face of risk, beckon our return, and, above all, invite us to play.

Generally, this book follows the “poetics” model of film scholarship described by David Bordwell, an approach that privileges formal concerns while rooting analysis in proximate aesthetic, economic, technological, and cultural contexts. Bordwell frames the analytical and historical questions of poetics this way: “What are the principles according to which films are constructed and through which they achieve particular ends? . . . How and why have these principles arisen and changed in particular empirical circumstances?”2 In the case of serials, this means closely examining their sounds, images, and stories, attending to the craft practices of filmmakers, and reconstructing the constraints that shaped the filmmakers’ choices. The form’s regular rhythm of action, cliffhangers, Rube Goldberg logic, and confident implausibility was the result of artistic problem solving, carried out in peculiar institutional contexts. This methodology emphasizes analyzing film form and narrative in detail and carefully taking stock of story structures, editing patterns, cinematography, and staging.

Such tactics, at home in a study of Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941) or Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958), may seem out of place in a book about routine formula films. Why should we devote energy and time to analyzing apparently simple movies? One reason is that we know so little about them. Serials are deceptively familiar. Their basic conventions and components are identifiable after two or three episodes, and this can give historians a false sense of mastery. To paraphrase Viktor Shklovsky, serials swiftly cover themselves in “the glassy armour of familiarity” and “cease to be seen and begin to be recognized.”3 That armor has tended to deflect scholarly inquiry, consigning sound serials to the province of passionate fans who are not so easily dissuaded from “seeing.” The majority of writing on sound serials consists of large-scale taxonomies of genre types and studio outputs, or exhaustive catalogs of chapters, performers, production staff, repeated footage, and the like.4 Genre guides and episode-by-episode commentaries, many of them sharply observed, provide an overview of conventions, some evaluative guidelines, and even a rough canon. They tend not to explore serials’ film-historical specificity, their distinctive relationship to Hollywood aesthetics, or the precise methods by which they organize viewer experience. In contrast to the fans’ often obsessive attention to interesting minutiae, the best scholarly work on sound serials has, so far, focused on context rather than the films themselves. Recently, Guy Barefoot has undertaken a meticulous and illuminating study of sound-serial distribution and exhibition during the 1930s, and Rafael Vela has written extensively about the form’s economic and cultural circumstances.5 Both works provide an invaluable background to the present volume, even as they highlight our need for an account of storytelling and style.

Another reason for analyzing sound serials is the insight they can offer into cinematic storytelling in general and Hollywood filmmaking in particular. Because they are so bare-bones, sound serials are virtual laboratories for suspense and action. If Hitchcock built cathedrals of suspense from fine brickwork of intersecting subjectivities and formal manipulations, sound serials used Tinkertoys. Because of this, we can plainly see narrative armatures and variations. Where Hollywood features provide motivations, psychologies, and complex style to naturalize and efface the telling of the tale, sound serials reach back to more rudimentary but nonetheless graceful practices of silent one-reel films made before 1912. Cliffhangers that remain riveting despite shopworn gimmicks shed light on the basic processes behind, and the limits of, cinematic suspense.

Finally, though marginal, sound serials are firmly rooted in the studio era, often referred to as the period of Hollywood classicism. Debates about the explanatory value of classicism have raged since the term was first formalized in Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson’s tome The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, published in 1985. Without detouring through those debates, we might safely note that sound serials challenge some principles of classicism, like unity of time and comprehensibility, while obeying others, like goal orientation and continuity editing. In broadening our view of Hollywood beyond feature films, serials can deepen our grasp of studio-era norms, classical or otherwise.

Serials also deserve our time because they are only apparently simple. As we will see, basic principles yield sophisticated variation. With a tight set of conventions in place, like an episode’s five-part structure, or the regular and timely interruption of catastrophe, serial filmmakers experimented to hold their audiences and keep things fresh. Constraints set clear limits, encouraged proficiency, and enabled innovation. Stunt crews at Republic, for instance, refined action choreography in fight routines that breathe with kineticism, while editors at Universal excelled in building new sequences out of stock footage. Our detailed look at Daredevils of the Red Circle (Witney and English, 1939) and Perils of Nyoka (Witney, 1942) will show how screenwriters and directors distinguished their work by adjusting the regular alternation of exposition and action scenes. Moving directly from a fight through a chase and into an entrapment might create a continuous chain of action, but it also required methods for shoehorning exposition in along the way. Balancing action against plot constituted an art among serial creators. Alternatively, screenwriters might outdo one another in frantic absurdity by packing ideas together, speedily introducing and resolving situations, as in the opening of The Phantom Empire. Like a game of few rules that generates complex play, serials are easily learned but offer opportunities for masterful variation. By studying them, we can observe filmmakers’ ingenuity in handling a narrative blueprint, solving creative problems, and recombining standard parts. They testify to the constructive advantages and artistic possibilities of formula.

Art at the Margins: A Historical Overview

This is a work of poetics rather than straight history. However, an overview of the production, critical reception, and intended audience of the sound serial will help situate the analyses that follow. Sound serials had a good run. Columbia, Universal, Republic, and tiny houses like Mascot, Regal, and Principle Pictures produced over two hundred twelve-to-fifteen-part chapterplays between 1930 and 1956. During the 1940s the three largest producers each released about four serials a year, enough to supply independent neighborhood and rural theaters with an episode a week.6 They represent a minor but remarkably sturdy production trend that did consistently solid business on tightly controlled budgets. Variety explained, “Turning out serials is a tough grind that permits neither wasted time nor motion. . . . They are a studio’s big sales lever with the smaller showshops and in the sticks. The back country exhibs don’t object to the ‘A’ product but they require serials and westerns.”7 At its height in the late 1930s and early 1940s, the form rated serious attention from the Hollywood industry amid a drop in attendance and disaffection with double bills. In March of 1940, Variety reported that “a rapidly increasing number of houses have added cliffhangers to their Saturday matinee shows during the past two years” and credited presold properties from radio and comics for the “skyrocketing” business.8 In November, the trade paper reported that the big five studios (Warner Bros., MGM, Paramount, RKO, and 20th Century Fox) were “gazing at the . . . cliffhanger takes with envious eyes” and predicted that they would “take a flier into the serial field within the next year” to get in on the “secure profit-grabbing possibilities of the chapter films” with their “fixed market.”9 The serials’ ascendance was brief, and these films rarely registered on Variety’s radar during the remainder of the decade. Still, the form persisted at the margins of the industry until the 1950s, when its target audience of eight-to-sixteen-year-olds migrated to television and the studio system was finally dismantled.10

By all accounts, making a sound serial was an arduous but efficient affair. Budgets were miserly, with Republic and Columbia spending between $140,000 and $180,000 per series on average and Universal between $175,000 and $250,000.11 This was roughly equivalent to a stand-alone programmer from the respective studios, but stretched across triple the running time. Titles were set and publicized to exhibitors in advance, leaving the production staff to envision a story that could support such an outsized project.12 Teams of writers penned phonebook-sized screenplays that ran to several hundred pages. Republic’s pressbook for The Lone Ranger (Witney and English, 1938), for example, brags that the final film contains some 1,800 scenes, as compared to 400 to 500 in a regular feature.13 The cutting continuity, a detailed log of every shot in the film, for the twelve-chapter Ghost of Zorro (Brannon, 1949) lists a staggering 2,657 shots.14 Producing a narrative at this scale demanded rigorous proficiency. Assistant directors broke the shooting down by location and actor on production boards, which would serve as daily schedules.15 Two directors routinely shared filming, alternating preproduction and shooting day to day. Neither would have time to screen rushes, and so depended on the money-minded producers to check their work. Shooting out of continuity was the Hollywood norm, and serials pushed it to an extreme. Recalling his work at Republic, William Witney described shooting master shots for six different chapters from a single camera position on a recurring set in one day, and then moving in to mediums and close-ups.16

Studios allotted a mere four to six weeks for shooting, which translated to sixteen-hour workdays for the crew.17 To handle inevitable delays due to weather, serial units shot exteriors first, keeping a cover set available in case of rain. This usually meant that stunt and action scenes would be finished first, using doubles, and the principals’ interior scenes were scheduled later. Filmmaking ingenuity helped make the most of tight schedules and budgets. Witney reports having made the twelve-chapter King of the Mounties (1942) in only twenty-two days, shooting locations with the leading man and a small troupe of doubles standing in for the rest of the cast. He filmed quickly and without sound, and then brought the principals in to film dialogue on a soundstage, standing before projections of still photographs shot on location.18 Witney pushed the serial mode of production to its limits, but his choices typify priorities and production practices: action first, dialogue and story second. The editorial staff went to work before the shooting stopped, logging footage according to scene and episode each day, so that they could begin final cutting immediately after production wrapped.19 Jack Mathis, discussing Republic, estimates that each episode took one week to edit and postproduce (including music, sound effects, etc.). The unrelenting rush continued into the serial’s distribution, as studios released chapters as soon as half of the episodes were complete. While the first installment was playing a matinee, the seventh was still being cut and scored.20

Those involved in this breakneck creation made no pretense of artistry, and few film critics deigned to comment on serials’ aesthetic merits. Only the Motion Picture Exhibitor, a small trade paper aimed at independent theaters, consistently reviewed serials, and it provides an invaluable view of the form’s shifting qualities during the studio era. Each of the 214 short reviews published between 1934 and 1958 (including reissues) indicates the serial’s likely market and concludes with a rating, usually “fair,” “good,” or “excellent.” Above all, the Exhibitor critic valued speed, originality, production value, and the potential for adult appeal. Juveniles were assumed to be the core viewership, but orbiting around them were “serial fans,” “parents,” “addicts,” and “initiates.” A film pitched straight to the youngster trade might receive praise, as White Eagle (Horne, 1941) does: “It’ll have the kids sitting on edge and that’s what serials are for. EXCELLENT.”21 Generally, though, acclaim was reserved for films with cross-generational appeal, defined variously in terms of pace, action, suspense, budget, and eclecticism. Drums of Fu Manchu (Witney and English, 1940) reached “excellent” because “its action-bent and suspenseful end makes top serial entertainment.” Th...