![]()

1

Virgin of the Secret River

Arturo Álvarez, director of the Guadalupe Monastery archive for twenty-five years, writes in his book on Guadalupe of Spain that “I lived in her shadow many years during which I had the opportunity to acquire the deepest knowledge about the past of her sanctuary. I developed a fascination and passionate love for this Virgin whose face is almost black.”1 Álvarez’s devotion is representative of the village surrounding the monastery. Twenty-first century residents visit the Virgin several times per day, praying to her or simply meditating while sitting in the sanctuary. Tourists swarm the place on weekends, coming from different regions of Spain and numerous other countries. The shrine has been a significant pilgrimage site for seven centuries.

Yet, because the Virgin represents the soul of late medieval Christianity, the village of Guadalupe has an ambiguous history. As Álvarez finally told me after many hours of conversation, during the beginning centuries of the sanctuary, many of the villagers were Jews or conversos.2 The association between the monastery and the Jews and conversos is alive in the twenty-first century. Local shops sell Judaica (Jewish religious objects) along with statues of the Virgin. Merchants occasionally display posters of geographic points that would be of interest to Jews. A number of local women wear the Star of David (while denying they are Jewish). Yet, according to historical narratives, all those who were secret Jews were either burned at the stake or banished in the late century. Guadalupe was repopulated by residents who were living on nearby lands owned by the monastery.3

The Guadalupe Monastery is in the heart of the Villuerca mountain range, a sanctuary of the Black Virgin of Guadalupe of Extremadura. It was considered the jewel of the Jerónimos—known to have a large number of conversos and judaizantes. A frequent story about the monastery and its monks is that the judaizantes heresy occurred at the foot of the Virgin.

Representing the Mother

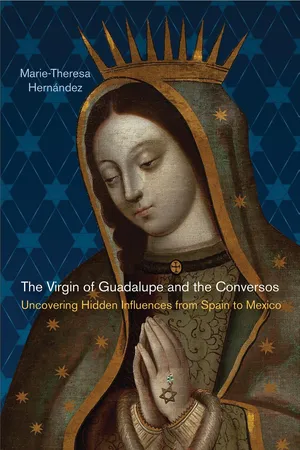

The desire for mother is primordial. As described by Julia Kristeva, “the Virgin Mother occupies the vast territory that lies on either side of the parenthesis of language.”4 It is evident at birth when the infant cries for her mother’s breast. The connection exists as an invisible filament that provides the requirements for physical and emotional survival. She gives life and retains an invisible cord with her offspring. The children of the mother retain the link to their original life-source—to her. Others expand this connection through devotion to the cult of a mother, such as the Virgin Mary, mother of Christ. Since late medieval times this Virgin has been mostly portrayed, at least in Europe, as a blond, blue-eyed young woman. In Latin America, she has been personified by a brown-skinned youthful adolescent girl in the form of the Virgin of Guadalupe of México (or Tepeyac). This Guadalupe has become the spiritual core of México. In the twenty-first century, her Basilica in México City is known as the most important Catholic shrine in the Americas.

Guadalupe of México’s predecessor, the Virgin of Guadalupe in Extremadura, Spain, is no young virgin. She is in full adulthood, with the serious demeanor of a woman with the responsibility of the small child sitting on her lap. The baroque form of her dress, placed on her by the friars, covers her original bright polychrome. Known as a Majestic Virgin or enthroned madonna, she, in actuality, is a sitting woman holding a child, both formed in cedar in the style of the medieval period.5 Her face is startling; she presents a stern and concentrated look. Yet she is also full of surprise. In contrast to her serious nature, her clothing is a celebration of red, royal blue, and gold, befitting a woman of nobility.6 She has refined features and skin black as coal. She is known as a Black Virgin or a Black Madonna. She is one of many hundreds known to have existed during the late Middle Ages in areas surrounding the Mediterranean.

While the Virgin Mary, as we know her in the twenty-first century, is a stylized version of a beautiful northern European woman in full bloom of youth, the Virgin of Guadalupe from Extremadura is a dark, solemn mater (mother) with a past that travels far beyond early Christianity. Her antiquity alone situates her as a mother of the world. Her importance is related to her fertility (Black virgins are commonly associated with fertility) and the child on her lap. A cousin to Demeter and Isis, her pre-Christian past is not often acknowledged, and yet a number of scholars believe she is of Celtic origin.7

Whereas the Majestic Virgins proliferated throughout southern Europe, the specific name of Guadalupe is directly linked to the sanctuary in Extremadura and even more so to Tepeyac. The popularity of the Mexican Guadalupe has overshadowed the Black Virgin of Spain. Guadalupe of Tepeyac has been such a dominant force in Marian devotion (adherence to the cult of the Virgin Mary) that most of her devotees are not even aware of her precursor in Extremadura. The Spanish Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe), a Black Madonna also known as La Morenita de las Villuercas, while being a mainstay of the nation’s culture and history, is rarely mentioned outside of Spain.8

Arturo Álvarez writes that she is the “authentic” one, her sanctuary being established in the early fourteenth century, two hundred years before Tepeyac.9 There is sentiment in Spain about this time difference, at least among some of La Morenita’s devotees. Sebastian García, the present archivist at the Guadalupe sanctuary in Extremadura, tells a story about attending a conference on the Virgin of Guadalupe and finding himself very frustrated because everything focused on the Mexican Guadalupe.10 He spoke in front of a large crowd of people, telling them that they were denying the importance of the first Guadalupe. He believes they did not understand the significance of what he was saying. His surprise at the slighting of La Morenita is reasonable considering that in 1520 Cortes, the conqueror of México, shipped a large quantity of silver to the Guadalupe Monastery and requested that three lamps be made in her honor.11 Yet historians of the Mexican Church have all but obliterated narratives of the Black Virgin, making it seem that she never existed. Most Catholics have no knowledge of her.12

In 2006 I spent several weeks in the village of Guadalupe in Extremadura. Upon return I gave my parents a postcard of La Morenita. They were surprised to see a Black Virgin. Their parish priest was so incredulous when told that the statue is black that my father decided to take the priest a photograph to prove she existed. The color of the image confounded the already predominant notion that there was only one Guadalupe, who is brown, not black, and she is in Tepeyac, near México City.

Although radio carbon dating places the Extremadura statue from the thirteenth century, her origins (according to legend) date to the year 587 A.D., when Pope Gregory the Great gave her to San Leandro in Spain.13 “En el tiempo que reinaba en España el rey Recaredo, que era de los godos de occidente” (In the time when Visigoth King Recaredo reigned over Spain14), the Church had rid all of Spain of the Arian religion. Arians were considered heretics because they did not believe in the Holy Trinity or the divinity of Christ. Recaredo himself converted to mainstream Christianity in 587, being influenced by his nephew, San Leandro, bishop of Sevilla (Seville). Leandro’s siblings were the Abbess Florentina, and bishops Isidro (Isidore), and Fulgencio (Fulgentius)—all considered saints. Florentina’s and Fulgencio’s relics were buried near the monastery several centuries later.15

A short time before the pope sent the statue to San Leandro, there had been a great epidemic of the plague in Rome. After this, Pope Gregory the Great led a procession through the city that carried a small image of the Black Madonna, a black-skinned version of the Virgin Mary. For centuries, throughout Christian Europe and the Spanish and Portuguese dependencies, when there were epidemics or great calamities, clergy would lead processions through cities with a significant religious icon, hoping this sign of devotion would bring a miracle. Gregory’s request was conceded and the city was soon miraculously saved from the pestilence. The phenomenon was attributed to this particular statue of the Virgin, which was normally kept in the pope’s oratory.

Leandro’s brother Isidro and a number of other Spanish clerics were said to have transported the gifts from Rome back to Spain. During their voyage they encountered a fierce storm in which they believed they were going to die. They took out the statue of the Virgin and knelt to pray in front of her. The storm then ceased and there appeared many lighted candles that illuminated the ship. The statue of the Virgin had saved them.16

La Morenita has an ancient story. It is said she was sculpted by San Lucas (Saint Luke).17 La Morenita is made of cedar with black skin, a cloak of red that is trimmed in gold, and a dress of blue. Her face has a chiseled quality, her eyes are large, she has a direct gaze, and her cheeks are full and her nose narrow with a small mouth beneath it. Her hands are large, somewhat out of proportion to the rest of her body, considered to be the norm for Black Virgins. She is sitting on a chair with her knees apart and the Christ child on her lap. At the time of the statue’s restoration in 1984, she measured 29 centimeters (11.41 inches) in height and weighed 3,975 grams (8 lbs., 7.6 oz.).18

Gregory’s gift of the statue and other relics was a significant event for the history of premodern Spain. It emphasized the great feat of San Leandro and gave the Church of Visigoth Spain the necessary instruments to convey its legitimacy.19 An ancient statue of the Virgin Mary was considered a relic. Since “the acquisition of relics” was one “of the major activities of the medieval church,” holy relics were kept in sanctuaries throughout Christendom and were frequently given as gifts to monasteries and churches.20

According to Scripture, the Virgin Mary did not die; instead she ascended into heaven. There are no relics related to her body. Therefore “venerated images” of her likeness are considered as holy as any bodily relics would have been. According to medievalist Wilfred Bonser, the Black Virgins are the most revered of all of Mary’s images.21 In evidence of this, when the pope gave San Leandro a special gift, it included a small cedar statue of the Black Virgin along with a number of religious relics.22

Virgin of the Secret River

The story of the small statue of Guadalupe contains the motif of inventio—devotion toward an image that is miraculously found “after it had been lost or hidden away from infidels for centuries.”23 According to legend, in the early eighth century, as the region was being overrun by Moors, Guadalupe was buried in a cave high in the mountains west of Toledo.24 Although Maria Isabel Perez de Tudela y Velasco reports there are no documents to substantiate the following narrative, allegedly “a number of holy clerics carrying relics, while escaping from Sevilla in advance of a Moorish invasion, reached a place that was close to the banks of the Guadalupe River.” In the margins of a codex, an unidentified writer explains (with no date) that clerics encountered a small shrine where they found the relics of San Fulgencio.25 Perez cites a different source stating the saint’s relics were actually brought to that location by the fleeing clerics.26 Sometime by the thirteenth century, the Virgin appeared to a cowherd named Gil Cordero and asked that a sanctuary be built in her honor at the spot where she said her statue would be found.27 The sanctuary was constructed near the River Guadalupe, in Extremadura, an isolated region on the road between Toledo and Lisbon.

The image has remained at the center of Spanish culture and importance for seven centuries. The origin story (Cordero’s vision) is repeated continuously. A number of scholars who have written about the Mexican Guadalupe attribute the name of the original Spanish Guadalupe to River of the Wolves—guada meaning river, lupe meaning wolves. Guadalupan scholar David Brading indicates that “‘river of wolves’ is a symbol of the Virgin conquering demons and idolatry,” which correlates with Ecija’s account of the statue being a gift to San Leandro for having conquered...