CHAPTER 1

Fires

From the beginning of recorded human history, fire has been both comforter and destroyer. The terrible conflagrations that leveled Rome in A.D. 64 and London in September 1666 are but two examples of the destructive force of one of nature’s most terrifying elements.

In nineteenth-century urban America, when many buildings were close-packed, ramshackle wooden structures, the warmth of the fireplace and wood stove and the light of the oil and gas lamp were decidedly mixed blessings. It took but one careless moment to set a building ablaze. With fire brigades usually nonexistent or poorly staffed and equipped, the orange glow of an unconfined flame could spread at frightening speed, destroying lives and property indiscriminately until burning out of its own accord.

Even today, with all of our modern firefighting methods, fire takes a heavy toll. In the United States, property loss resulting from residential fires alone in the three-year period ending in 2008 amounted to $6.92 billion; during the same period, nearly fifteen thousand civilians died or were injured in those blazes. Even a state as well protected as New Jersey has not been spared: fire fatalities in the year 2010, the last for which statistics are currently available, totaled 73, with 393 injuries. That year, there were 30,841 fires statewide. Losses were in the millions.

Newark—October 27, 1836

New Jersey’s first great fire struck Newark on a cold afternoon, October 27, 1836. It was a few minutes after three o’clock when a lodger in a German boarding house on East Market Street first discovered the flames. Within minutes, the old two-story, wood-frame structure was a roaring inferno. Moments later, the adjacent frame buildings on the east and west, and sheds to the rear, were burning furiously. Soon rows of shops on both sides of Mechanic Street were ablaze, with flying embers carrying the fire quickly to a three-story carriage factory on the corner of Broad Street. The fire raged up Broad, consuming factories, shops, and fine old homes, until it met the flames burning along Market Street. In less than three hours, an entire city block bounded by Broad, Mechanic, Mulberry, and Market Streets was engulfed.

The five Newark fire companies that responded to the first cries of “Fire!” found their efforts crippled by a lack of water and bursting hoses. Hundreds of citizens pitched in to help the fire laddies, but when it became apparent that the fire could not be stopped, all efforts turned to the rescue of property in the path of the flames. Volunteers frantically emptied houses, offices, factories, and sheds of their contents, jumbling furniture, bedding, clothing, machinery, and merchandise in mid-street.

Firemen from Rahway, Elizabeth, Belleville, and New York City—which dispatched six companies by ferry and railroad flatcar—responded to Newark’s frantic calls for help to “battle bravely with the demon of devastation,” as one writer put it. Only through superhuman effort were firemen able to save two of Newark’s landmarks, the venerable First Presbyterian Church (its vestry building was badly scorched) and a fireproof two-story brick building on the corner of Mechanic and Broad Streets occupied by the State Bank. A garden between the bank building and the approaching flames acted as a natural firebreak.

Hurrying to Newark with the Elizabeth fire companies, two naval officers, Captain Gedney of the U.S. surveying schooner New-Jersey and Lieutenant Dayton Williamson, volunteered to check the fire’s spread by blowing up buildings in its path. A frantic search for sufficient gunpowder proved futile, however, and for five hours the fire continued its work of devastation, incinerating Captain Gillespie’s Washington Hotel, a new four-story, fireproof brick building, along with chandlery, clothing, and millinery shops, grocery stores, carriage factories, a brass foundry, workshops, sheds, offices, factories, rooming houses occupied mostly by poor families, and private dwellings—in all, nearly fifty structures, several of them substantial. According to the Newark Daily Advertiser, the losses totaled $120,000, a goodly sum in those days, only $75,000 of which was insured.* Fortunately, there were no fatalities.

“Great apprehensions were excited at one time that the whole eastern side of the city would be destroyed,” reported the Daily Advertiser, “but it was preserved, and great as the calamity is, there is still great cause for thankfulness for the protecting care of a merciful Providence.” At the height of the fire, showers of sparks kindled blazes at several points north of Market Street, but the vigilance of volunteers who stationed themselves on rooftops and in backyards with buckets of water prevented the flames from spreading beyond the city block already involved. “One case of intrepidity and generous self-sacrifice deserves special mention,” said the Advertiser. “Alexander Kirkpatrick, a journeyman Mechanic, signalized himself in saving Asa Torrey’s house, upon the roof of which he was sometime exposed to the billowy sheets of flame from the adjoining building, pouring water from buckets handed through the scuttle, at the peril of his life.” Kirkpatrick, as modest as he was heroic, declined to accept a “handsome fee” offered as a reward for saving Torrey’s brick home. Another intrepid soul, unfortunately anonymous, dashed into a burning building to save an eleven-year-old boy stranded on a blazing rooftop. Cradling the boy in his arms, the man jumped two flights to the ground, deposited the boy on the street unharmed and disappeared into the cheering crowd.

The day after the fire, Newark’s Daily Advertiser attempted to put the best face it could on the city’s greatest calamity. “A large number of workmen have been turned out of employ, and there must be a temporary suspension of a great amount of business, but on the whole there is great reason for thankfulness, that so many of the sufferers will be able to sustain themselves,” said the paper. “It is not probable that so extensive a fire could have occurred in any other portion of the city, though the burnt district is comprised in the very centre of business, with less suffering. There are some individual cases where the evil will be sorely felt, but the largest portion of the buildings destroyed were old frame workshops and warehouses, from which the personal property was chiefly rescued, and but few families have been turned out of doors.” The truth, unfortunately, was that Newark’s twenty thousand people were just then falling victim to a nationwide manufacturing depression that would culminate in the Panic of 1837. Thousands of workmen were soon thrown out of work, joining those burned out in the fire of 1836. Many of the charred factories and shops south of Broad Street lay in ruin for years.

Cape May City—September 5, 1856

Cape May City’s claim as America’s oldest seaside resort dates to 1801, when Ellis Hughes, who owned a tavern and hotel, advertised in the Philadelphia newspapers a night’s lodging for seven cents. “The subscriber has prepared himself for entertaining company who use sea bathing,” proclaimed Hughes, “and he is accommodated with extensive house room, with fish, oysters and crabs and good liquors.” Cape May’s popularity surged when the steamboat General Jackson began making regular weekly runs from Philadelphia to the cape in 1816. An added stop at New Castle, Delaware, opened the resort to passengers from the southern states, firmly establishing Cape May’s reputation as a favorite playground for the wealthy seeking to escape the South’s humid summers.

As the resort’s popularity increased, entrepreneurs lavished thousands of dollars on ever larger wood-frame hotels, many of them enormous, ornate structures that could accommodate hundreds, and in some cases, thousands of guests. Henry Clay and Abraham Lincoln were two of the resort’s earliest distinguished visitors. Clay’s two-week stay in 1847 reinforced Cape May’s position as the country’s finest seaside resort. More numerous than the politicians were the planters from Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia, who rode their thoroughbred horses on the wide beaches during the day and spent the evenings gambling in the casinos.

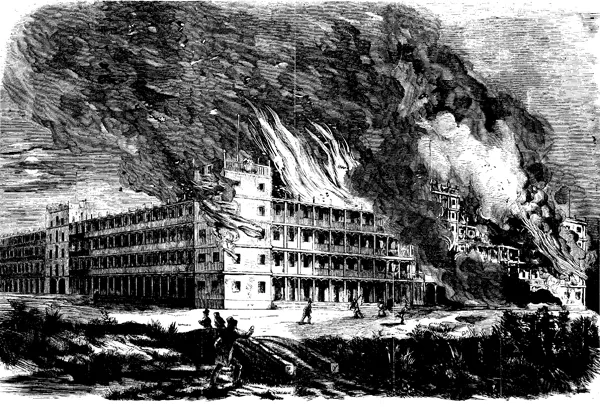

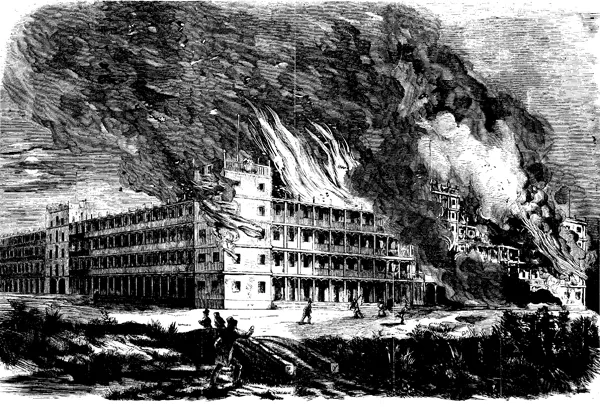

Among Cape May’s remarkable hotels, the most remarkable of all was the Mount Vernon, built by a company of Philadelphia investors at Broadway and Beach Avenues at a cost of $125,000. Said to be the largest hotel in the world, the Mount Vernon was simply immense. “Although the hotel . . . was capable of accommodating 2,100 visitors, it was not finished,” reported the New-York Daily Times. “It was designed to . . . occupy three sides of a hollow square, or court yard, and the front range and one wing were up. . . . The building was constructed entirely of wood; it was four stories in height in the main, with four towers, each five stories in height. Three of these towers occupied the corners of the building, and one stood midway of the only wing. In addition to these towers there was an immense tower six stories in height in the centre of the front. The entire structure, both outside and upon the court-yard, was surrounded with wooden piazzas that extended from the ground to the roof, with floors at each story.” The wing was five hundred feet in length, and the front extended another three hundred feet. “The dining room, which was 425 feet long and 60 feet wide, was capable of accommodating 3,000 persons. There were 432 rooms in the building . . . [with] stables for fifty horses, carriage houses, ten-pin alleys, etc.” The Mount Vernon, said the paper, was “celebrated . . . for the superior accommodations the building offered its guests. The interior was well-finished, and the apartments were larger and more comfortable than usual at watering place hotels.” Unique among early hostelries, the Mount Vernon boasted a bathroom in each room. The hotel’s luxurious furnishings alone were valued at $94,000.

On the evening of Friday, September 5, 1856, the hotel’s manager, sixty-five-year-old Philip Cain, and his family—sons Philip Jr. and Andrew, teenage daughters Martha and Sarah, and Mrs. Albertson, Cain’s housekeeper—were alone in the hotel, or so they thought. Cain’s wife and several other children were in nearby Vincentown, but the Mount Vernon’s manager, a busy season just behind him, preferred the quiet of his magnificent hotel. No doubt, too, there was much work to be done before the hotel could be closed for the winter.

Shortly before eleven o’clock, after the family had retired for the night, fire broke out in three different places. Unable to escape, and overcome by the dense smoke, manager Cain, his two daughters, one son, and the housekeeper perished in the flames. Son Philip, although badly burned, saved himself by jumping from a second-story window. Within an hour’s time, the Mount Vernon was a complete loss. Its buildings constructed almost entirely of wood, Cape May City was surprisingly unprepared for a fire, even a minor one: There was no fire apparatus of any kind for miles. Only because the Mount Vernon stood at a considerable distance from the resort’s other hotels was the city saved from total ruin.

On the Monday following the fire, New Jersey newspapers reported that the wife of an Irishman who claimed Cain owed him $100 had been arrested and committed to jail on a charge of arson. “It is said that she had the day before, and up to late in [the] evening previous, been heard to utter the most serious threats against Mr. Cain.”

Inexplicably, the loss of the Mount Vernon, and a fire that razed the Mansion House the following year, failed to alert Cape May’s town leaders to the transparent need for a city fire department. Although the newer hotels were now equipped with their own water tanks, fire hoses, and employees trained to detect and fight fires, the resort was a tinderbox in search of a match. The United States Hotel, built in 1850 and one of the largest and best equipped on the island, was the target of so many arson attempts that a vigilante force was established in 1863 to protect both the building and the town.

Cape May City—August 31, 1869

Disaster struck once again on August 31, 1869, the very year that President Ulysses S. Grant vacationed at the United States Hotel. It was 2:30 in the morning when the dreaded flames were first discovered flickering in a two-story building occupied by Peter Boyton, known locally as the Pearl Diver. Packed with flammable material, including Japanese paper kites and lanterns, lacquer boxes, and cotton goods, Boyton’s shop was soon burning fiercely. A handful of would-be firefighters who, acting without direction, broke in windows and knocked down doors unintentionally vented the fire, which then spread relentlessly from one building to the next. The town’s hook and ladder truck arrived, along with the mayor, W. B. Miller, who attempted to bring some order out of confusion, but the uncoordinated efforts of a thousand or more volunteers were no match for the fire, which had now gained an insurmountable headway. Unfortunately for the city, the wind, stirring only lightly when the fire began, now began to blow briskly toward the ocean, carrying sparks and flames to all of the buildings east of the Pearl Diver.

The United States Hotel, sold only the week before to a New York investor for $80,000, stood directly in the path of the fire, protected by a twenty-seven-thousand-gallon water tank and a corps of employees determined to save it. They hung wet blankets over the balconies facing nearby burning buildings and played almost all of their precious water on surrounding structures, but the intense heat and smoke proved too much for the hotel employees. Forced to retreat, they could only look on helplessly as the wooden structure first smoldered and then burst into flame. Wind-driven sparks soon ignited the American House and the New Atlantic Hotel, together with a score of lesser buildings in between. When it became clear that the United States Hotel was doomed, “the guests hurriedly poured out in a great crowd, men, women and children, scarcely clothed, and unnerved by fright,” reported the New York Times. “Each person was burdened with such articles of personal property as he had been able to snatch up in the hurry and terror of the moment; men bore out trunks, and women and children struggled under unwieldy loads of clothing. But there was little time to save property, and hardly more than enough to make sure that no human being should be swallowed up in the hot fire.”

After the United States Hotel caught fire, it was at once clear to everyone that no part of the city was safe. “The town was now thoroughly alarmed and aroused,” continued the Times. “Every hotel, every house, every store was emptied of its inmates, who fled inland with such part of their portable property as they had been able to collect. Nor was the alarm groundless or the haste uncalled for. The flames spread with terrible rapidity.” From the United States Hotel the blaze extended in almost every direction, ultimately devastating one-fourth of the city, consuming in its fury “the heart and beauty of the pleasant town.” Several of Cape May’s finest hotels were saved almost by chance: Congress Hall (where Lincoln once vacationed) was protected by a row of trees that refused to ignite; the LaPierre House escaped the flames when its owners tore up its carpets, dowsed them with water, and spread them on its roof; the Columbia House owed its preservation to the “almost superhuman exertions” of five employees who, wrapped in wet blankets, managed to cling to the rooftops of adjoining buildings, extinguishing every firebrand that threatened devastation.

“The escape of the Columbia House from destruction is looked upon as the most wonderful occurrence of this terrible drama,” said the Times, “and is altogether owing to the clear foresightedness of two or three of its employees in tearing away some smaller out-buildings and in the judicious use of the hotel’s supply of water. The scene from the roof of the Columbia was terrifically sublime. The red flames checked the fall of the frame buildings, and the large clouds of smoke, interspersed with sparks, floated out to sea, and hung like a pall above the surf.” The three steam fire engines from Camden that arrived by special train at noon could do little more than hose down the smoldering ruins. Losses from the fire exceeded $300,000.

Unwilling to acknowledge that the town’s sprawling wooden hotels might themselves be the cause of its troubles, Cape May searched for a culprit, convinced that the fire was of incendiary origin. Peter Boyton, the Pearl Diver, who had himself lost $1,000 in cash in the fire, was hauled before the mayor only to be discharged after a brief hearing that produced no proof that he was the arsonist. “There immediately followed a tremendous burst of applause from all present,” reported the Cape May Ocean Wave, “a large proportion being ladies.” A $1,000 reward offered by the mayor and City Council for the arrest and conviction of the incendiary proved ineffective. Cape May once again began to rebuild; within two years, all evidence of the fire had been erased.

Cape May City—November 9, 1878

A newspaperman writing in the 1870s called Cape May “the favorite watering place of Philadelphia.” It was, he wrote, “a town with a population of about 3,000, which is increased to nearly 6,000 by the transient visitors of a summer season. The town is 81 miles from Philadelphia, on a point of land at the most remote portion of the southern extremity of New Jersey. The Town of Cape May is of itself not attractive, and the fashionable hotels are all built on what was formerly Cape Island, once separated from the mainland by a small creek that has been filled. Cape Island is about 250 acres in extent, and, besides the hotels, is occupied by numerous cottages.” Among the twenty-four hotels, he wrote, the largest were the Stockton, Congress Hall, the Co...