![]()

1

Measuring Environmental Inequalities in the Philadelphia Area in 2010

In the introduction, I’ve presented Chester City and Port Richmond, two Philadelphia area communities facing severe environmental inequality, in an effort to give the reader a bit of the flavor of what it is like to live there amid the environmental justice struggles each community faces. In this chapter, I’ll discuss my research and how I determined which communities in the Philadelphia area faced extreme environmental inequality, compared with others. I will also provide some numbers and maps to illustrate my findings.

The focus in this chapter and the historical ones that follow is on the Philadelphia Metropolitan Area (also known as “Greater Philadelphia”), which includes the City of Philadelphia (which is also Philadelphia County) and the four Pennsylvania counties that border Philadelphia (Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery). It also includes three New Jersey counties just across the Delaware River from Philadelphia (Burlington, Camden, and Gloucester).

The Philadelphia area is especially suited for a study of the development of environmental inequality due to its industrial, environmental, and social histories. The city and its suburban manufacturing “satellite cities” have a long history of intense industrial activity, which gave rise to appalling levels of pollution and environmental damage. Philadelphia also played a long and fascinatingly contradictory role in the history of race and ethnic relations in the United States. It is the place where Quakers and others spirited slaves out of the South on the Underground Railroad; but it is also the place where African Americans were murdered and their homes burned in a series of antiblack riots during the same period in history. Throughout Philadelphia’s history, its African American job seekers faced a brick wall of racial discrimination when they sought a share of the prosperity of the booming manufacturing plants all around them. Yet Philadelphia is also one of the U.S. cities where there has always been a prosperous black middle class and black elite. It has also always been home to many impoverished and near-poor white people, some of whom struggled to make a living without dying in their industrial workplaces. Thus, Philadelphia’s history illustrates the multidimensional nature of both race and social class as conditions shaping environmental inequality.

At the beginning of Philadelphia’s industrial age, most of the largest industrial plants in “noxious” industries—industries producing smoke, noise, and bad smells—were located not in the center of Philadelphia, but rather in industrial suburbs on the outskirts of the city. Those who worked there tended to live close by, in small rowhomes near the plants. Farther away from the city were the homes of the privileged—those who may have invested in factories but did not work in the factory. These wealthy communities are as much a part of the story of how environmental inequalities were produced as are poor and working-class communities; yet, the privileged, and the way in which their racial and class privileges are mobilized to obtain environmental privilege, are usually ignored in environmental justice studies.1

Since the Philadelphia area is characterized by a high level of social class inequality, it also includes a number of these privileged communities, allowing for an examination of their role in the development of environmental inequality. For this reason, it was important to include the suburbs as well as the city in this study of environmental inequality.

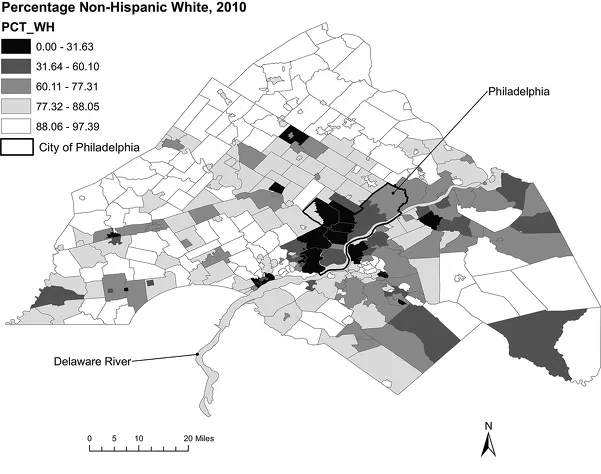

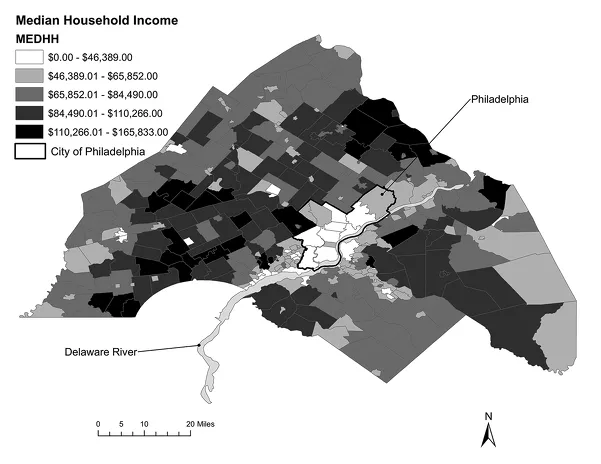

To trace communities through history, it is necessary to choose a definition of “community” that carries with it some type of social identity and sets it apart from other communities. Municipalities (boroughs, cities, and towns) have a social identity, including social class and racial/ethnic identities; and they specialize in certain types of employment. They also have legal boundaries, clear borders that set them apart from other places. Thus, communities outside Philadelphia are defined as the 339 boroughs, cities, and townships bordering Philadelphia but outside its boundaries. Within the city, it was a bit more difficult to define “communities.” Census tracts did not qualify, as they have no social identity; they were also much smaller than suburban towns. Neighborhoods were better than census tracts, since they have strong social identities; but like census tracts, they were too small in area to compare with suburban towns. Also, in Philadelphia neighborhood residents debate and disagree about the boundaries of their neighborhoods—in fact, there is even disagreement over how many neighborhoods actually exist in the city. The best definition for communities was the twelve Planning Analysis Areas used by the Philadelphia City Planning Commission, each of which contained more than one neighborhood.2 (See the appendix for a more detailed description of methodology.) Census data were added to maps of the twelve Planning Analysis Areas and the suburban towns that surround Philadelphia, yielding a picture of the racial/ethnic composition of all Philadelphia area communities and the median household income of each community (see maps 1 and 2).3

Since this study examines the development of environmental inequality, perhaps it is time for some discussion about what “environmental inequality” means. Although all terms connected with environmental justice tend to have multiple meanings, it is fair to say that environmental inequality describes a wide range of conditions in which the environment in one place is less beautiful, healthy, or safe than the environment in another place.4 One type of environmental inequality is distributional inequality, which refers to difference, unevenness, or inequality in the distribution of environmental “bads” (such as polluting factories, power plants, or waste disposal facilities).5 Distributional inequality can also describe an unfair distribution of environmental “goods” (such as tree cover, access to parks and other places for safe recreation, and access to public transportation); in the Philadelphia area, as in most places, environmental goods tend to be clustered in very different places than environmental bads.

In the Philadelphia area, “environmental bads” include Superfund sites; electric power plants; polluting factories listed on the Toxic Release Inventory (TRI); commercial hazardous waste treatment, storage, and disposal facilities (TSDFs); incinerators; municipal, construction, and industrial landfills; large sewage treatment plants or sludge management facilities; and trash transfer stations (listed in table 1, along with a breakdown of the points assigned to symbolize the hazardousness of each type of facility). Using GIS, I mapped each facili...