1

Introduction

Orthodox Jews and Language Socialization

The lights come up. In the middle of the stage stands a young man wearing a black hat, full beard, and black suit with no tie. He holds the microphone close and begins chanting a slow Hasidic niggun, a wordless melody, in a minor key. All of a sudden the rhythm section starts up and the singer switches to an upbeat style. The young men and women in the audience sing along, dancing energetically and pumping their arms to the beat. The music is unmistakably reggae, complete with faux Jamaican accent, interspersed with Hebrew words like Hashem (God), golus (exile), and Moshiach (Messiah).

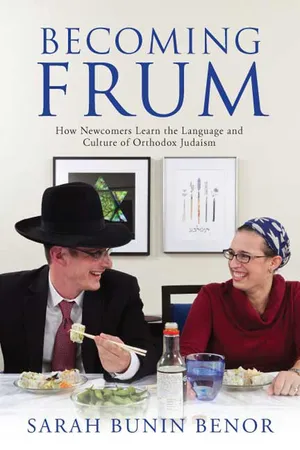

The unique blend of hip-hop and Hasidic style that launched Matisyahu’s career is unlikely among those who were raised Orthodox. But it is just the kind of hybrid self-presentation we might expect from ba’alei teshuva, also known as BTs. Matisyahu and other BTs exist in a cultural borderland between their non-Orthodox upbringing and the frum (religious) communities they have joined. These two worlds differ greatly in dress, food, language, and other important aspects of everyday life. This book describes how BTs navigate this borderland. How do they learn the many cultural norms of their new communities? Which do they choose to make their own? Do they give up burritos and pad thai in favor of gefilte fish and noodle kugel? To what extent do they incorporate Yiddishisms into English sentences and mention God frequently in their informal conversations? Why do some, like Matisyahu, maintain aspects of their pre-Orthodox identities, while others wish to pass as FFB (frum from birth)?

This is a book about becoming, in-between-ness, identity, and community. Based on ethnographic and sociolinguistic fieldwork in an Orthodox community with many BTs, I show how individuals deal with transitions in identity through the creative use of language and other cultural practices. I demonstrate how they and others see themselves, to varying extents, as part of both worlds. I describe the self-consciousness they experience throughout their transition and how their interactions with community veterans and other novices help to socialize them. And I show how the case of BTs relates to the broader phenomenon of adult language socialization: how newcomers learn new ways of speaking that position them as members of a new community.

The idea for this book came about when I was researching language at a Chabad center in California. A few of the BTs who frequented the center found out that I knew Yiddish and asked me to teach an informal Yiddish class. After the first session, one student said to another, “We’re going to sound so FFB!” It was then that I realized how important language is for BTs as they integrate into Orthodox life. While speaking Yiddish is important among Hasidim, I knew from previous observations that a distinctive English, with influences from Yiddish and Hebrew, is the language of choice in non-Hasidic Orthodox communities around the country, including the one I ultimately studied in Philadelphia.

I began floating the research idea among some Orthodox friends. One said, “You mean you want to study how Ivy League–educated people can speak like they’re new immigrants?” Another friend smiled and told me a joke about BTs overextending linguistic rules: “What do BTs drink? Ginger Kale!” (Orthodox Jews pronounce El/Ale, one of the names of God, as Kel/Kale in conversation, but only a newcomer would apply this rule to an English word.) It became clear to me that studying the language of ba’alei teshuva would yield fascinating data, rich in ideology and humor. It also became clear that the study should not focus only on language, as the Hebrew and Yiddish words people use are intimately connected with the ways they dress, the foods they eat, and their relationship with God and their communities.

I read up on Orthodox Jews and linguistic anthropology, complementing my graduate education in sociolinguistics. The more I read, and the more I spoke to colleagues in Jewish studies, linguistics, and anthropology, the more I realized that this study could have something to contribute to those fields. While there was a good deal of research on ba’alei teshuva, no study had analyzed their language. And while many linguists and anthropologists had researched how children learn language and how adults learn a second language, especially in the burgeoning field of language socialization, there were few studies of how adults learn new ways of speaking their native language. I knew I had found a niche, but it was not until I had completed my fieldwork and analyzed the data that I realized what my contributions to those fields would be.

Orthodox Jews

My research has led to three main findings about Orthodox Jews: (1) being Orthodox involves not only a system of belief and religious observance but also a set of cultural practices; (2) through subtle linguistic cues, Orthodox Jews indicate their locations along various social axes, including the Modern Orthodox to Black Hat continuum; and (3) ba’alei teshuva, through their hyperaccommodation and deliberate distinctiveness, complicate the culture and social axes of Orthodoxy. The sections that follow introduce these findings and offer the background necessary for subsequent chapters.

Belief and Spirituality, but also Community and Culture

A central finding of this book is that religion cannot be separated from social life and practice; religiosity and religious transformation involve an interplay between the spiritual and the cultural, between the individual and the communal.1 Orthodox Jews are expected to conform not only to halacha (Jewish religious law, literally “way” or “path”), but also to cultural practices—although there is less communal censure for cultural nonconformity. We see this interplay in the languages that enrich the English of American Jews, especially Orthodox Jews: the holy languages of the Torah, rabbinic commentaries, and prayers (Hebrew and Aramaic); the Eastern European Jewish language spoken by the ancestors of many, but not all, community members (Yiddish); and the national language of the country to which Jews have diasporic allegiance and transnational ties (Israeli Hebrew). All BTs in the current study use words from textual Hebrew and Aramaic, and most also use features from Yiddish and Israeli Hebrew. But there is more ambivalence about Yiddish and Israeli Hebrew, as they are not considered central to religiosity. These findings are in line with anthropologist Ayala Fader’s study of a Hasidic community in Brooklyn.2 There, however, Yiddish is much more prevalent as a spoken language, especially among men, and Israeli Hebrew plays a minimal role. Even so, both her study and my own point to the interplay between religion and culture in Orthodox life, manifesting in reverence for both Hebrew and Yiddish.

There is some debate within frum circles about the relationship between religion and culture. Some rabbis involved in helping newcomers transition to Orthodoxy preach that individual spiritual transformation and halachic observance are central, and “walking the walk” and “talking the talk” are peripheral. BT training programs support this assertion, as their curricula focus on Tanach (Jewish Bible), Talmud (compilation of rabbinic commentaries), and Shabbos observance, rather than cooking, dance, or Yiddish.3 Even so, the current study indicates that culture is also an important part of being—and becoming—frum. Many BTs take on cultural practices with great enthusiasm, sometimes even going beyond the norms of FFBs, a phenomenon I refer to as hyperaccommodation.4 Other BTs, especially in their early stages of Orthodox identification, avoid elements of frum culture that they see as peripheral to halacha and continue to participate in aspects of secular culture that are not common among FFBs. This selective accommodation and deliberate distinctiveness serve to diversify frum communities. In addition, when BTs do not fully accommodate, they effectively critique the cultural conventions of Orthodox life. When halachically observant BTs use contemporary slang or add blue trim to their black velvet kipah, they send the message—intentionally or not—that they consider religious mandates to be more important than cultural conformity.

Another finding of this study is that religious and cultural practice may take precedence over full acceptance of the underlying system of belief. Although some Orthodox outreach programs do offer proofs of God’s existence, and many BTs become Orthodox only after being convinced of the truth of the Torah, newcomers may take on religious laws and cultural practices before they fully accept the theology.5 For example, a new BT who has not internalized the concept of divine providence might still answer a frum friend’s “How are you?” with “baruch Hashem” (blessed be God), conforming to the communal norm. This phenomenon, which has also been reported in several situations of religious and social transformation, is reminiscent of a biblical story. At Mount Sinai, the Children of Israel responded to the revelation of the laws, “All that the Lord spoke we will do and we will hear/understand” (na’aseh v’nishma).6 The order of the two actions suggests that knowledge and spiritual transformation can be secondary to religious behavior, a trope common among BTs.

Na’aseh v’nishma also points to the importance of community in religious observance. The nation responds to the giving of the law together in the first-person plural: we will do and we will hear, rather than each individual answering in the singular. The centrality of the community persists in contemporary Judaism: certain prayers can only be recited when a quorum of ten is present, and because traditionally observant Jews cannot drive on Shabbos, they tend to cluster residentially within walking distance of a synagogue. As I found in my research, community is central to frum life, and the tight-knit, supportive social networks are a major draw for many BTs. As such networks tend to do, they also create pressure to conform to communal norms, not only in religious observance but also in cultural practice.7 Some BTs embrace that communal conformity, and, as the case of Matisyahu suggests, others creatively tap into the cultural repertoires of Orthodox and American life to highlight their in-between status.

Ideology and Practice

The linguistic and cultural practices common in Orthodox communities are not arbitrary; they are influenced by a number of ideologies, beliefs, and worldviews.8 These include belief in an omnipotent, omniscient God (Hashem); an expectation that the Messiah (Moshiach) will come; a complex system of laws (halacha) and customs (minhagim); reverence for great rabbis past and present and confidence that their knowledge of Torah endows them with special insight in other spheres (daas torah); high value attached to the study of biblical and rabbinic texts (“learning”); maintenance of distinct gender roles; connection to the recent Eastern European Jewish past; sense of Jewish peoplehood and descent from the biblical Children of Israel; connection to the contemporary state of Israel; and a sense of distinctiveness from non-Orthodox Jews and non-Jews.

As previous literature has shown, these ideologies, though not exclusive to Orthodox Jews, are central to Orthodox life.9 They are relevant to the current analysis because they influence cultural practices, like dress, food, and language. For example, Orthodox Jews frequently discuss Bible stories, give their children biblical names like Rochel (Rachel) and Shmuel (Samuel), sing Hebrew songs, and use Hebrew words within their English—practices connected to the ideology of descent from the biblical Children of Israel, the value of study, and the attachment to contemporary Israel. Many Orthodox Jews prefer Eastern European foods, minor musical modes, and Ashkenazi (Central/Eastern European) pronunciation of Hebrew words, all of which are influenced by a connection to Eastern Europe. The differences in women’s and men’s dress, activities, and language are dictated by a complex set of ideologies surrounding the relationship between gender, modesty, and piety.10 Many practices are also affected by Orthodox Jews’ complex and stringent system of laws and customs, such as the length of women’s sleeves and the avoidance of gossip and profanity. The belief in an omnipotent, omniscient God encourages the use of common interjections like baruch Hashem and im yirtse Hashem (God willing). An expectation that the messianic age is imminent leads to the formulaic dvar torah (sermon) ending: “May we be zoche (merit) to witness the coming of the Moshiach speedily in our days.” And reverence for rabbinic leaders influences the home-based custom of prominently displaying portraits of elderly, bearded rabbis and the yeshiva-based practice of addressing esteemed rabbis in the third person. While previous literature on Orthodox Jews discusses many of these cultural practices, especially Yiddish and conservative dress, this book highlights the centrality of culture in differentiating Orthodox Jews, not only from non-Orthodox Jews but also from each other.

Demographics of Orthodox Jews in America

To understand the analysis in this book, readers should be familiar with the demographics of Orthodoxy. In 2001, studies estimated the U.S. Orthodox population between 530,000 and 700,000, which is about 10 to 13 percent of the U.S. Jewish population.11 Because of high birth rates, these numbers are poised to jump in the coming decades. Currently, at least 39 percent of the Orthodox population is under age eighteen, compared to 20 percent of the overall Jewish population.12 The U.S. Orthodox population is heavily concentrated in the Northeast, especially the greater New York area, but there are also Orthodox communities in most major U.S. cities and some smaller towns, as well as in several cities in Canada, Europe, Latin America, and elsewhere. While Orthodox communities today have high retention rates, there are also defectors, as recent research has pointed out.13

Within Orthodox communities, a number of social, cultural, and religious distinctions are salient. These oppositions and axes, which emerge from community discourse and cultural practice, are important for understanding the socialization of BTs. As BTs transition from non-Orthodox to frum, they also necessarily position themselves along several social axes (with varying levels of intentionality). As they do so, they contribute nuance to this social landscape. Not only do they add a new axis (BT–FFB), but, through unusual cultural blends, they also complicate some of the other axes.

Orthodox and Non-Orthodox Jews. Although I use the term “Orthodox” in this book, I note that this term seems to be less common among insiders than frum.14 Many of the frum people that I encountered in my research say that they prefer not to make distinctions like “Orthodox” versus “non-Orthodox.” Several talked about klal yisroel—a unified Jewish people—or commented, “Jews are Jews!” And many have close ties and regular interaction with non-Orthodox Jews, especially with prospective BTs who take classes in Orthodox outreach centers and visit them in their homes. Even so, there is a strong ideology of distinctiveness from non-Orthodox Jews and their forms of Judaism.15 For example, I heard several FFBs and, especially, BTs contrasting their communities, synagogues, and forms of observance to those of “secular” Jews or “Reform and Conservative” Judaism, o...