![]()

1

Filming the Transitory World We Live In

Settings, Literary and Cinematic

Of the three elements usually said to be constitutive of narrative in both its literary and cinematic forms—action, character, and setting—criticism has routinely seen the place where the action unfolds, where characters do and are, as little more than backdrop or frame. Setting is most important, perhaps, when context is considered to be in some significant sense determinative of character or a limiting factor on action, as for example in the somewhat special case of naturalism, with its tendency to underplay free will and promote environment, broadly considered, as the driving force of the plot. But even in naturalist texts, setting is usually not what stories are about. In traditional filmmaking, of course, settings in a material sense are also the “where” in which principal photography takes place. They are indispensable in the sense that they make themselves available for the staging of the action to be recorded by the camera, without which there is no film, at least in the conventional sense.

The ontology of the literary text is somewhat different. Setting in a work of fiction can be crucial, with the evocation of lived space an important concern of the novelist. In Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet (1957–1960), for example, the city named in the title becomes a kind of composite character brought to life by a gallery of diverse inhabitants featured in a linked series of fictional sketches. But a literary setting can also be so lightly drawn, or even elided (as in Philip Roth’s Deception [1990], which is all dialogue), as to become virtually invisible, save for the minimal filling-in provided by cooperative readers, who must imagine a world in some sense as the place where the characters are and on which the action achieves some kind of existential purchase. This seems true enough even if this “where” is a mental landscape whose events can in some sense be narrated. An extreme example would be Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake (1939). Consider also the stage of sorts on which thought assumes verbal form through the device of interior monologue, a convention that assumes a speaking self in some sense and thus an intra-mental place for speaking; Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying (1930) exemplifies a variety of different ways in which such monologues can be presented. Even when it is not mostly dramatic interchange, a literary text can foreground character and voice. This remains true for the contemporary novel even though pictorialism and visuality have been strongly valued at least since Joseph Conrad affirmed, in the preface he wrote for The Nigger of the “Narcissus” (1897), that “My task, which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel—it is, before all, to make you see.”1 Conrad, of course, was simply assenting to a general aesthetic tendency in Victorian fiction writing, what was often called word painting, a desire for the engaging image that first photography and then the motion pictures came into existence in order to satisfy.2

Despite the influence that pictorialism has exerted on modern fiction (reinforced by the occulting of the narrator’s presence favored by Henry James), not every novelist would agree to the visual imperative Conrad promotes, at least not as a general rule. In Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day (1989), for example, the principal action unfolds in what is only vaguely designated as a huge, presumably ancient country house called Darlington Hall. Despite its importance to the tale told by Mr. Stevens, its head butler, Darlington Hall is never accorded even a short paragraph of rudimentary description, a neglect that indexes Stevens’s inability to objectify and analyze the surroundings, physical and social, in which his narrowly circumscribed life has unfolded, so inevitable, and right, do they appear to him. The butler’s silence about the physical environment in which his life plays out becomes a key element of self-characterization. Its particularities are so strongly present to him that they do not need to be communicated to those who do not share this domestic space. His psychological state is overdetermined by the sheer weight of a seemingly endless sameness that is insulated from the immense changes endured by the nation he inhabits, which has barely survived the Pyrrhic victory of World War II. His tale thus begins with the first of many inventories of his own state of mind, without more than the slightest gesture toward setting a scene: “It seems increasingly likely that I really will undertake the expedition that has been preoccupying my imagination now for some days . . . [that] may keep me away from Darlington Hall for as much as five or six days.”3

Though they listen in extenso to what Stevens has to say about himself, readers are not invited to share the perceptual or sensorial aspects of his experience in the setting that most perfectly defines and explains him. In order to visualize his world in even the haziest fashion, we are forced to deploy our inferential powers to broaden and particularize the selective accounts and musings his narrative makes available, conjuring up what is at best a vague image of Darlington Hall from our repertoire of cultural knowledge, especially our sightings of other oversized residences of an English aristocracy doomed to class extinction in an ever-leveling modern world. Stevens provides no self-portrait, nor indeed any description at all of the others who figure in the account he offers of his life in Darlington Hall. They are named for us and come to possess recognizable qualities of mind and self as Stevens recounts his interaction with them. But, failing even the most rudimentary of physical accounts, we cannot imagine them as individuals of a certain stature, look, or presence.

Assigning himself a mission that takes him by stages far from Darlington Hall, in the course of the narrative Stevens finds himself simultaneously tracing a vigorous arc of inner development, one that returns him, albeit transformed, to his long-time home. In the end, he possesses his experiences as objects of a troubled consciousness and perplexed moral analysis, even as he ruminates about the place that had hitherto completely contained him. Unexpectedly, Stevens discovers on his travels the significance that place can possess, as each day’s journey is defined by the particularities of the countryside and villages he passes through. The excited presentism of his observations of this, for him, brave new world beyond his employer’s country house is communicated by increasingly detailed diary entries. We see that he has now learned to look. Preventing the reader from imagining Darlington Hall in a comparable fashion reveals itself as a key element of characterization in this modernist tale of introspection, moral doubt, and eventual, resigned embrace of the unavoidable costs of “being,” of persisting, no matter what, in a moyen de vivre that can be defended, if not unhesitantly, as of supreme value. Stevens comes eventually to understand life as a zero-sum proposition in which the choice of one form of living precludes others, but this spiritual turning occurs only after his monologue deploys what might be considered an anti-setting that fails to evoke what F. R. Leavis would call any thick sense of lived experience, underpinned by freedom and choice. Stevens does not think to limn the contours of a world that the reader, too, might be able to find a place to live vicariously within.

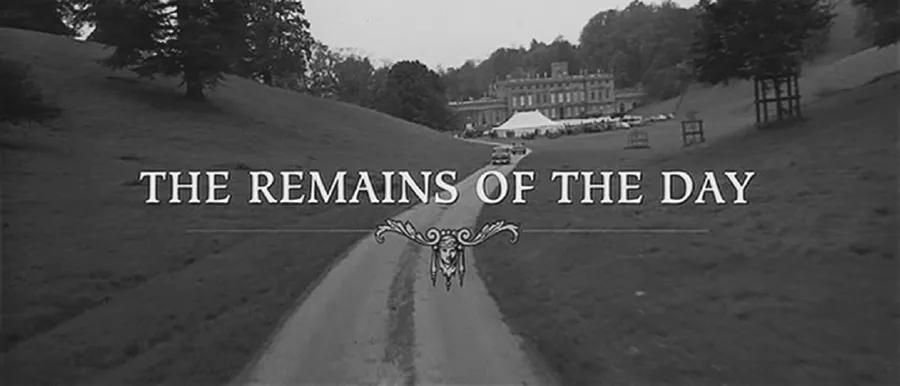

In the Merchant/Ivory film adaptation (1993) of the same title, however, Darlington Hall comes to life in full particularity, its image, which dominates the beginning and ending of the film, indicating the objective immensity of its atavistic opulence. An impressive seventeenth-century manor, Dyrham Park, Chippenham, was commandeered for the impressive opening shot of the film, and a nearby Georgian property was used for the closing, “helicopter-out” sequence, while the house’s interiors were shot in a number of places. Thus the film’s “Darlington Hall” is assembled from different real locations in a process that admirably suits its typicality. The history of the house immediately emerges as the film’s proper subject. Its endurance and renewal provides the requisite plot, replete with happy ending, as even the moral failings of its aristocratic owner, as well as the changing mores of a postwar society newly committed to the welfare state, do not prevent its being reclaimed as the home of yet another wealthy gentleman who will carry on the self-indulgent lifestyle of his predecessor, who has died in disgrace, leaving no issue to perpetuate family tradition.

Tellingly, the film’s establishing shot locates Darlington Hall as its furnishings are being auctioned off, and a voiceover (a passage from a letter read by Miss Kenton [Emma Thompson], the former housekeeper) reveals that the now dilapidated and presumably culturally irrelevant property had been scheduled for demolition. The film thus does not begin, as the novel does, with a crise de conscience striking the most compliant representative of the serving class, but with the distinct possibility, viewed with alarm, that Darlington Hall, and the Edwardian social relations sustaining it, might be swallowed up in a postlapsarian modernity devoted to the parasitical dismemberment of the once-glorious. But this possibility becomes less likely as the narrative admits immediately of a gesture toward restoration. Persisting in the auction battle for the house’s furnishings, the new owner buys one of the ancient family portraits, preventing its removal and establishing himself as a legitimate, if self-adopting, heir.

FIGURE 5 The camera swoops in to focus on Darlington Hall in transition as its contents are auctioned off in the opening of The Remains of the Day (frame enlargement).

Appropriately, as it is soon revealed, this is a movement back to the future. Darlington Hall has been purchased by a former guest, a rich American politician, Trent Lewis (Christopher Reeve), who wishes to relive the pleasant, and momentous, time he spent there during an international conference more than a decade earlier. Mr. Lewis has decided that to make this happen he must retain the services of the aged head butler, Mr. Stevens (Anthony Hopkins). Both the property and the man who has long overseen its functioning figure in the narrative of regeneration and reconciliation that the film traces. First captured performing his duties (opening the long-closed dining room shutters in a gesture not void of symbolism), Stevens is only barely a main character, rarely seen in close-up, and only intermittently the source of voiceover that reveals the content of the letters he writes. He is not present in every dramatic scene, including and especially those that detail the unfortunate political flirtation of his previous employer, Lord Darlington (James Fox), with Hitler’s foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop (Wolf Kahler), and a thinly disguised version of Sir Oswald Mosley (Rupert Vansittart), the leader of the British Fascist Union. Von Ribbentrop, entering Darlington Hall, remarks to a subordinate that this residence, and others like it, are going to be among the prizes of a successful German invasion, defining one aspect of what might be at stake in the war then only being contemplated.

Thus the past that the film traces is not in the least limited to Steven’s reminiscences. In contrast to the subjective approach of the novel, Stevens is conjured up by the impersonal narrator not as the source of meditations about the various questions, some profoundly ethical, that occupy his reflections in his novel, but as a laboring presence within Darlington Hall, as a human figure who expresses in part what the house means as a lived space where domesticity regularly becomes transformed into political theater. In effect, Stevens makes Darlington Hall “be” through the ways in which he helps it function, and his life is presented as subordinate to the continuing fact of its persistence. The house dominates the film, evoked as a social environment in constant motion, dependent on the complex orchestration of a considerable number of different tasks. Many of these are accorded reverential visual attention (the polishing of antique brasses, the sweeping of stone floors, the careful laying out of banquet tables, the keeping of account books, the carrying of heavily laden trays of food, the preparation of huge meals in a cavernous kitchen, and the careful stationing of impassive footmen at dinner). Darlington Hall is a location meant to convey power and wealth, a domestic site within which a multitude of human beings enact complex forms of hierarchy that connect it through informal statecraft to the governmental function of the ruling class. The house is animated by figures who are almost always glimpsed in purposive motion.

The narrative of their activity, devoted to “service,” reveals a series of more or less connected interior spaces that are eloquently expressive of the always connectable separation between the rooms set aside for the use of residents and those in which the huge staff work and find homes of sorts. These spaces also of course serve as platforms for the performance of the film’s actors, who actualize the book’s minimal evocation of character in full ontological particularity, becoming present, visible, and knowable individuals (their historicity expressed through period dress and manner) rather than briefly evoked memories conjured into brief existence only by and in the butler’s troubled consciousness. In the novel, the only shape the other characters are permitted to take is filtered through a restless memory searching for answers to existential and ethical questions it labors to frame. In the film, like the house in which they live and work, Stevens and fellow residents simply are, existing in and for themselves, even as their presence and labor define the complex social environment contained within Darlington Hall while obscuring the nature of the wealth and inherited privilege that sustain this community.

A novel like The Remains of the Day may avoid setting (and description in general) in order to focus the reader’s attention on voice or, more broadly in this case, on ideas and the mental geography of an individual’s limited interrogation of self. However, such abstraction, such a suppressive representation of setting (or of human figures) is less likely, or desirable, in a medium that confronts more readily the semiotic immensity of the seen and so is less likely to ignore the opportunity to provide striking, readable images of what the novel’s protagonist passes over in silence. Stevens becomes one more object for the camera rather than the source of a knowledge imparted through all-encompassing monologue whose rhetorical exclusions and inclusions prove crucial. The viewer comes to know the butler and his world with a perceptual fullness denied the novel’s reader, but this objectivist approach comes at a representational price. It means that the erstwhile main character’s état mental cannot be accorded the depth it comes to possess for readers. Only the silent monologue of his musings could afford Stevens, whose public face is all helpful abnegation, a roundness of character, an inner depth that belies the carefully contrived shallowness of his public self, with manner, accent, and bearing all in conformity to long-established professional protocols. In the film, what he thinks or feels is only rarely capable of restaging in dialogue. It briefly burbles to the surface in slippages of one kind or another, often in facial expressions pointing toward something left unsaid, but this hardly matters since the focus of the fiction has decisively shifted from character to setting. Perhaps better, we might say that the film details the multilayered interdependence of character and setting, portraying a location of built and occupied space as lived.

Lavish, eye-satisfying pictorialism is a key element in the genre of literary adaptation Andrew Higson and others have termed “heritage cinema,” a popular and acclaimed form of British filmmaking for which The Remains of the Day was enthusiastically claimed by Merchant/Ivory Productions. In heritage films, settings like Darlington Hall index the social standing of a class that thinks itself as propertied:

Most of the costume dramas seem fascinated by the private property, the culture, and the values of a very limited class fraction in each period depicted, those with inherited or accumulated wealth and cultural capital. . . . The national past and national identity emerge in these films as very much bound to the upper and upper middle classes, while the nation itself is often reduced to the soft pastoral landscape of southern England, rarely tainted by the modernity of urbanization or industrialization.4

The filmmakers report being drawn to Ishiguro’s novel because of the opportunity it offered for being turned into a heritage film, making prominent a sense of spectacular, unusual place that might be easily construed as the object of pleasurable, if hardly unconflicted, nostalgia. Conceived as a sequel to the same production team’s spectacularly successful Howard’s End (1992), the screen version of Remains not only repeats the critically acclaimed romantic pairing of Emma Thompson and Anthony Hopkins, but, with no little success, attempts to reconfigure Darlington Hall as a symbolic space equivalent in terms of its social significance to the less grand but still impressive eponymous country house that figures so centrally in the earlier production.5 Viewed as the residential center of a rich farm whose fields are improbably but appropriately displayed as being worked by horse-drawn equipment, Howard’s End represents one of heritage cinema’s most memorable tableaux, with what seems a deliberate evocation of Jean-François Millet’s rural landscapes and the nostalgia for an agricultural past that they so movingly evoke.

In the two Merchant/Ivory productions, a dwelling configures, or makes manifest, the interrelationship of the characters who inhabit it; ownership is contested and finally resolved even as the property, if transformed, endures triumphantly, providing an image of solidity in the face of thoroughgoing historical change. Because camera-style in this form of filmmaking is pictorialist, Higson writes, th...