![]()

1

The Artist Employee

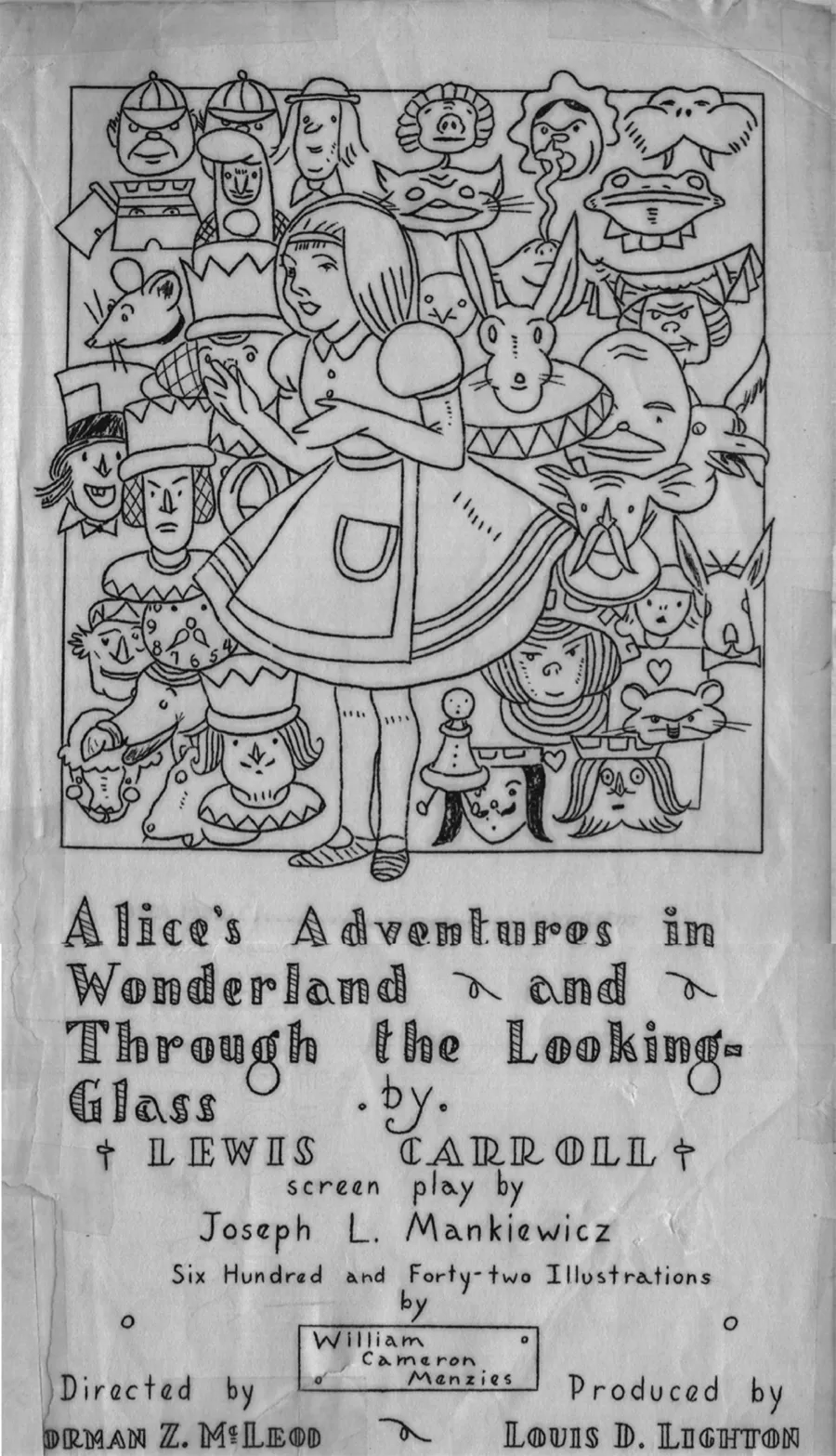

IMAGE 5 Illustrated script and storyboard for the film that would become Alice in Wonderland, c. 1933. Screenplay by Joseph L. Mankiewicz.

Writers Guild Foundation Archive, Shavelson-Webb Library, Los Angeles

INTERVIEWER: Now we look back at . . . the 1930s, as the Golden Age of Hollywood—

JULIUS EPSTEIN, writer of Casablanca: We didn’t think so at the time. We did not think it was Golden at all. Maybe a little Bronze here and there, but far from Gold [laughs].

—The Writer Speaks: Julius Epstein, 1994

[David O. Selznick] even gave me a screen test, which, after he saw it, he said I was definitely going to be a writer.

—Ring Lardner Jr., interview by the Writers Guild Oral History Project, 1978

In the winter of 1933, the steady foundation under Hollywood began to crack. Quite literally, the walls started to shake when the Long Beach earthquake rumbled its way across the Southern California landscape on March 10. But it was not the first seismic shift noted that year. In the weeks preceding it, the film studios were facing the rapidly falling box office sales. Although the wild success of sound film and audiences’ desire for escapism during the dark economic times of the Depression had ensured big box office numbers for a few years, the cost of sound conversion along with a decrease in box office sales finally forced the moguls to reexamine their spending habits. This belt tightening, in turn, pushed Hollywood’s creative talent to open their eyes to the potential power of unionization.

Across the United States, the situation for working and unemployed Americans was dire. In the richest country in the world, more than fifteen million workers were unemployed and looking for jobs that did not exist.1 In the middle of this national devastation, an American president came to power who used popular media as a central means to communicate with his suffering citizens. In the first of his “fireside chats” on March 12, 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt took to the radio airwaves to calm the public regarding the banking crisis, explaining clearly and in lay terms the notions of value, credit, and capitalism, and declaring a bank holiday. Roosevelt emphasized his confidence in the American people and American workers, whom he valued as “more important than gold.”2 Citizens were scared, and they were looking to their leaders for inspiration and for a clear path out of financial ruin.

The same was true for individual businesses and industries, including the Hollywood studios. The studios were indebted to stockholders and to personnel and feared that it would be impossible to pay off both debts with funds so tight. In January 1933, RKO and Paramount had gone into receivership, declaring their theater chains bankrupt.3 Studios were unable to meet payroll. MGM cobbled together the funds to pay its employees in cash, but Universal suspended contracts, and Fox told its employees outright that they would not be paid. Across the eight major studios, the outlook was grim, and a shutdown looked likely.4 Employees were anxious and concerned. On February 3, 1933, ten screenwriters met informally at the Knickerbocker Hotel in Hollywood to discuss a growing number of concerns. Writers working within studio walls had previously gathered under the moniker “Screen Writers Guild,” or “The Writers,” as a social organization. Now they gave the name “Screen Writers Guild” (SWG) new meaning and a heightened sense of urgency.5 As stirrings of unionization began among screenwriters, the studio heads were anxious to deter any talk of the Hollywood workforce organizing. Louis B. Mayer, the MGM studio boss, stood in front of his employees with a plan to counteract the effects of the Depression.

The preceding months had been difficult for Mayer. Irving Thalberg, his vice president in charge of production, had suffered yet another heart attack—though the press reported it as only a bout of influenza. Even when Thalberg was available, tension between the two executives was on the rise.6 The studio had barely made its payment to employees during the bank closure. At the last-minute the studio sold its lucrative Treasury bonds and in a dramatic—arguably cinematic—move, hired a private airplane on the East Coast to airdrop the cash to a line of grateful employees. Still, the studio’s cash flow was drying up, and selling more bonds was not possible. MGM needed bold action and got it: Mayer called an emergency meeting and gave the performance of a lifetime. Even though the SWG’s first meeting had occurred weeks before, screenwriters and historians have often seized upon this event as the moment of the Guild’s formation—a narrative that makes for a grander origin story for a union of people who tell stories. Inevitably, the event’s details may be embellished, but the actions have been documented in a wide array of memoirs, press reports, and oral histories. The story goes like this:

In early March 1933, Mayer called all of MGM’s directors, actors, department heads, and writers to the executive studio projection room. After letting the crowd wait for more than twenty minutes, Mayer entered, unshaven—perhaps, as many have noted, for the only time in his life.7 He was exhausted and red-eyed. In front of a massive crowd of creative personnel, Mayer declared that the studio was broke. As producer and legendary MGM story editor Samuel Marx describes: “He began with a soft utterance. ‘My friends . . .’ Then he broke down. Stricken, he held out his hands, supplicating, bereft of words.”8 The only way to save MGM, he implored, was for everyone to take a 50 percent pay cut. Philip Dunne tells the story as he heard it: “At the time I remember [fellow writer] Donald Ogden Stewart describing to some of us what had happened at MGM. He said Louis B. Mayer got up and pointed a finger at all the people who were listening to him saying, ‘We’ve got to take a salary cut.’”9 The emphasis was on the community sharing the weight of the studio’s future on their collective shoulders. Employees were given the impression that if everyone worked together, the crisis would be averted. After a pause, actor Lionel Barrymore proclaimed in his commanding, avuncular baritone, “Don’t worry, L.B. We’re with you.”10 But they were not. Fellow actor Wallace Beery rose from his seat and stormed out.11 Ernest Vajda, screenwriter of The Merry Widow, questioned the economics of Mayer’s declaration. The pay cuts, he believed, were premature: “I read the company statements, Mr. Mayer. I know our films are doing well. Maybe the other companies must do this, but our company should not.”12 Barrymore boomed back: “Mr. Vajda is like a man who stops for a manicure on his way to the guillotine.” At this point, according to some accounts, the entire room went into peals of laughter and applause; others suggest that the chuckles were more dutiful.13 The drama continued.

May Robson, an Australian-born actress who began her career as a Vitagraph star in 1916, rose from her chair and declared with great aplomb, “As the oldest person in the room, I will take the cut.” As if working from a script, eight-year-old child star Freddie Bartholomew took his cue and piped up, “As the youngest person in the room, I’ll take the cut.”14 It was then, when Mayer had the full attention of his audience, that he called for a vote to show a declaration of allegiance and a willingness to accept the salary reduction. Frances Goodrich, screenwriter for The Thin Man, It’s a Wonderful Life, and Father of the Bride, remembered, “Everyone got pious and scared.” The vote was cast with tears of solidarity, and the employees agreed to accept the loss in pay. Mayer promised that he would personally see to it that every penny was reimbursed someday. The tone was solemn as the room was rocked by the new reality of Hollywood economics. But walking back across the iron bridge to the front office buildings, Samuel Marx overheard Mayer gloating to his right-hand man and talent expert Benny Thau, “So! How did I do?”15 Albert Hackett, Goodrich’s husband and writing partner, said of the meeting, “Oh, that L. B. Mayer, he created more Communists that day than Karl Marx.”16

As at other studios, there was economic necessity behind Mayer’s appeal to his talent for retrenchment. Across Hollywood, creative workers took pay cuts and ensured their studios’ safe financial grounding. Lester Cole, writer of Objective, Burma!, remembers how forty employees of Paramount Pictures were invited into a projection room to hear that the Depression gave the studio no choice but to cut the salaries of actors, directors, and writers by 50 percent.17 The dramatic slashing of incomes was later cited in part as a pretense, a subterfuge play-acted by moguls in front of employees to foster fidelity in a time of economic crisis. After six weeks, Mayer and other executives restored workers’ pay to their full salaries. But the deducted sums for those six weeks were never reimbursed. And there was more to this story than Mayer let on.

While teary-eyed directors, actors, and writers voted to give back half their salaries to save the company, not everyone working at MGM or other studios was forced to make this financial sacrifice. What became apparent to the creative workers over the ensuing weeks was that two groups of personnel were never asked to cut back: the studio executives and the below-the-line (craft) employees who were covered under the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE) union contract. That the studio executives did not dock their own salaries came as little surprise; but the durability of the IATSE’s contract, even in the face of budget cuts, provided insight and inspiration to embryonic creative talent unions.

Only a few weeks before the MGM meeting, IATSE workers, angered at the possibility of pay cuts, considered a strike across the studios and flatly refused the reductions. The union argued that its members were not paid well enough to be able to afford the cuts and still feed their families. At MGM, Thalberg’s biographer wrote, most employees were performing “backbreaking work with few guarantees, little protection, and no rights.”18 Though they were paid little, their jobs were vital. Studio heads Jack Warner of Warner Bros., Harry Cohn of Columbia, Carl Laemmle of Universal, Winfield Sheehan of Fox, and Mayer gathered and ultimately agreed not to cut the earnings of those who made fifty dollars or less a week. Cognizant of the critical role these workers played in the daily functioning of the production machinery, the moguls bent to this massive union. For the first time, a union held its ground against the industry. Although word of this victory did not reach the talent in time, writers, directors, and actors agreed that from this point forward they would never be swindled by the studios again. As Philip Dunne remembers, Mayer’s cuts and the creatives’ realization of their mistreatment were “what kicked off all of the so-called talent guilds.”19 It was clear to Hollywood talent that the best way to ensure their power was to stand up to the studios as unions. For many writers, the newly formed Screen Writers Guild now looked like a necessity if they wanted to protect their wages and basic labor rights.

Although altercations between studios and employees had been common earlier, a revolution in the employment structure of the American film industry truly began in the 1930s. The below-the-line craft union’s successful stand against the studio heads catalyzed the above-the-line creative talent to organize across the studios. Writers recognized that although individual contracts and salaries were manageable, protection by a union contract was more secure. The studio heads used every trick at their disposal to prevent the talent guilds—in particular the Writers Guild—from unionizing. But the transformation of the Screen Writers Guild from a social group to a trade organization was already happening, starting with a substantial increase in its membership. Two months after its first meeting in February 1933, the Guild had 173 charter members. By April, studios began to pay full salaries again and, apart from MGM, even offered retroactive pay. Guild membership had climbed to 343 active members by February 1934, far exceeding total membership during its days as a social club. In July 1934, with 640 members, the Guild started publication of the Screen Guilds’ Magazine, a joint venture with the Screen Actors Guild (SAG). At this point, 90 percent of all screenwriters working in the industry were members of the Guild.20 But by the end of 1936, only two years after membership reached 750, the Guild was nearing extinction. A bitter three-year jurisdictional battle ensued, ending with the US Supreme Court interceding to name the Screen Writers Guild the sole organization sanctioned to negotiate with the studios on behalf of the writers. It took another two years, until 1941, before the Guild started its first negotiations with the studios. Finally, after many twists and turns, the Guild secured its first contract with the Hollywood studios in 1942, nine years after the creation of Screen Writers Guild as a union.

This chapter reviews the state of labor for Hollywood writers in the late 1920s and early 1930s, and traces the evolution of the Screen Writers Guild from a social club into the critical era when writers battled bitterly with studio heads for jurisdiction over a screenwriters’ union and for a minimum basic agreement (MBA). During this period, writers gained significa...