![]()

Part I

Women and Christian Fellowship in the Early Twentieth Century

The YWCA’s experience of dramatic growth at the turn of the century underscores the importance of the activist energies of religious organizations in the “woman movement.”1 While struggles for the ballot have come to be the most visible manifestation of this upsurgence, the reform and community-building activities of the YWCA and other women’s groups nurtured by evangelical revivalism left an indelible influence on what would come to be called feminism.

As described in the introduction, the YWCA of the USA was the product of mid-nineteenth-century women’s transatlantic organizing, in which the success of the Young Men’s Christian Association inspired the creation of a parallel women’s organization.2 The first YWCAs were convened by middle-class and elite Protestant women to look after the spiritual welfare of young women affected by urbanization and industrialization. Already in 1858, when the Ladies Christian Association was founded in New York City, US women in urban centers were organizing prayer circles and social services for workers on the model of the London groups. The US organization took root on college campuses, where student YWCAs attracted the participation of the growing population of women in higher education. Working in concert with student YMCAs, they established a strong influence on the missionary movement. While many Christian groups took on reform projects and foreign mission work in the second half of the nineteenth century, both city and campus YWCAs stood out for their interdenominationalism and single-sex ethos. This fostered an inclusiveness that brought mainline Protestants together outside of the atomized setting of churches. In a context where male representatives of church bodies often “expressed opposition to women’s activism,” the YWCA created an outlet for women’s energies “where there were no men to hamper them,” in the estimation of Anne Firor Scott.3

The late-nineteenth-century groups established an institutional identity premised on what the YWCA called the “association idea”: “that all kinds, conditions, and classes of young women in the community shall be united in Christian fellowship, each to give according to her ability, each to receive according to her capacity,” according to a 1907 pamphlet.4 Founders envisioned the YWCA as a boundary-crossing space. The space was both literal and figurative, as the organization’s mission to bring women together in the spirit of Christianity was interknit with the construction of facilities to provide the recreation and services a diverse population required. One association author underscored the excitement that accompanied the creation of these tangible spaces, noting that “women’s groups in the past had had little opportunity to feel the thrill of ownership.”5 This celebration of the power of women’s unity included the conviction that the association had the unique ability to bring egalitarian social values to life. Though “the experience, advice and help of older women [were] always needed,” the YWCA endeavored to be a group “for young women, and largely by young women.” The YWCA’s identity was perhaps most defined by its commitment to reaching across the divisions of social class: “inside the Association there can be no class distinction—from the board member, the wife of the wealthy manufacturer, to the girl who works in the factory.”6 YWCA facilities offered workers spiritual and material services in an attempt to create wholesome outposts in noisome cities. Housing and employment training and referrals proved popular in an urban landscape that was particularly inhospitable to single women. But however much the association positioned itself to transcend the boundaries of class, racial divides were largely left undisturbed. African American groups that were affiliated with the YWCA, where the logic of Jim Crow prevailed in administrative structures, brooked the inequalities of turn-of-the-century interracialism that were the cost of access to the institutional resources of majority-white organizations.7

In an effort to streamline administration and orchestrate growth, YWCA leaders brought the loosely affiliated campus and city groups together under a unified umbrella organization, the YWCA of the USA, in 1906.8 With its inception as a national federation, the YWCA of the USA joined a number of nationally organized women’s mass membership organizations that were simultaneously faith driven and dedicated to female-led social change. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, formally organized in 1873, was the largest in scope and membership, parlaying the battle to eliminate alcohol abuse into a comprehensive international campaign of lobbying and direct action in service of the purification of the public sphere. Affiliates of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, founded in 1896, discerned a divine mandate for women to pursue uplift as an avenue for racial justice. Created after a gathering at the World Parliament of Religions in 1893, the National Council of Jewish Women launched programming that claimed a place for Jews in the American body politic, provided direct social services to a growing population of impoverished immigrants, and linked its policy ambitions to those of the broader women’s movement. Nineteen years later, Henrietta Szold and her compatriots in a Zionist women’s study group created the transnationally focused Hadassah and launched a women-led public health infrastructure for Jews in Palestine.9

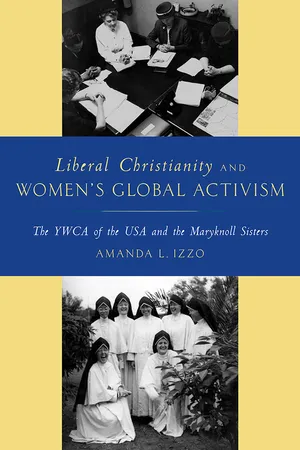

During the years in which the YWCA of the USA came of age, the Maryknoll Sisters were born. While the YWCA rode the cresting wave of Protestant women’s institution building and community work, Mary Josephine Rogers faced an ecclesiastical hierarchy that was suspicious of developments in the US Catholic Church and indifferent to women’s service in the mission field.10 The institutional differences between the YWCA and Maryknoll were particularly pronounced in the 1900s and 1910s. The Maryknoll Sisters, attempting to establish themselves within the rigorous framework of apostolic women religious, were in an embryonic state, while the YWCA, thanks to the support of wealthy funders and a well-established network of women’s voluntary clubs, had tremendous momentum. However, the nascent Maryknoll effort was built in part on the foundations established by Protestant women’s organizing. Though they were not in the same stage of growth as the YWCA, the Maryknoll Sisters were similarly impelled by the rise of women’s educational and professional opportunities in religious institutions. The sisters were also inspired and goaded by the successes of Protestant women in the mission field.11

In addition to presenting the background for the Protestant religious outreach that spurred the creation of Maryknoll, the following chapters explain how, in these early years, the YWCA combined the energies of the women’s movement with a liberal Christian quest to perfect society according to Gospel tenets. They show how the YWCA built the “association idea” into a national entity that was at once a vibrant membership group, a corporate provider of social services, and a hub of women’s religious, intellectual, and political life. The reach of the organization was considerable. It began a presence in six hundred cities and colleges as well as a handful of foreign missions, and within twenty years, four hundred more associations were added in all sorts of communities across the United States. Additionally, it oversaw dozens of new associations in foreign cities and schools.12 In tiers of organization that went from the community level to the national federation and ultimately to an international network, members and staff collectively advanced a faith in action that was a vital, if now underrecognized, presence in the Social Gospel and foreign mission movements. While scholars of the YWCA have documented the powerful impact of the organization on the early labor movement and the long civil rights movement, various dimensions of its story remain untold. This examination of the first decades of the organization highlights how an attempt to enact the ethics of Jesus inspired an innovative program of Christian advocacy that extended from small-group organizing to community-level programming and national electoral politics. At the same time that the challenges of international institution building steered the YWCA into an anti-imperialist revolt that reverberated throughout the foreign mission infrastructure, circumstances in the United States placed the organization in the reactionary crosshairs of a Red Scare that flared intermittently until the 1950s. In facing these challenges, YWCA women contributed to the vitality of mainline Protestantism as a launching point for local and global social engagement.

![]()

1

“Life More Abundant”

The YWCA and the Social Gospel

The first convention of the YWCA of the USA, held in New York City in December 1906, captures something of the alchemy responsible for the YWCA’s rapid growth in its first two decades: an emotionally charged mixture of evangelicalism, the Social Gospel, and ambitions for female-centered social change. The atmosphere of this and later national membership conventions must have felt something like a combination of a revival, Chautauqua-style edification, and a political convention. Programs were scheduled from morning to night, with hymns and prayer services, sermons and lectures, and procedural matters such as committee reports and membership resolutions. Representatives of community and campus associations gathered to hear from some of the most prominent figures in mainline Protestantism, with Charles Stelzle encouraging ministry to laborers, Robert Speer describing the “supreme good” effected by the YWCA’s work among college students, and John Mott waxing enthusiastic about the role the group could play in the “great advance” of “great Christian civilizations.”1 Passing motions to determine the direction of the organization, delegates enthusiastically participated in a simulacrum of the electoral machinery that then barred their access to it. The meeting was convened after several years of sometimes contentious negotiations over coordinating the efforts of autonomously operating associations. The tasks at hand were, first, the pragmatic work of articulating an institutional identity and determining the scope of association activities, and second, the inspirational work of issuing a charge for Protestant women to unite in the spirit of Christian service.

The women gathered in New York affirmed a YWCA plan of action with three points of emphasis: to serve as the “door through which young women are led into the Church of God,” to break down the “lines of class and caste” through cooperative service, and to unleash the “mighty power” of “earnest consecrated women” in solving the “many perplexing problems” of modern life.2 This plan fostered a synergy between the personalist passions of evangelicalism and the Progressive impulses shaping both women’s organizing and the Social Gospel movement.

By the YWCA’s sixth convention in 1920, which made the national press for its controversial calls for workers’ rights, women’s participation in electoral politics, and ecumenicalism, it became evident that this was an unstable alchemy. The dramatic increase in working-class women’s participation in association life, as well as the shifting religious affiliations of the rising generation of YWCA leaders and members, tipped the balance away from the evangelical concerns of piety, social morality, and personal salvation. Instead, an emphasis on the “social principles of Jesus” and Progressive coalition politics prevailed.3 This transformation opened the way for the YWCA to become a pacesetter in liberal Christian activism.

The YWCA’s institutional mission, the “ultimate purpose” adopted at the 1909 convention, can be credited with providing an expansive directive that inspired the search for a practical application of Gospel ideals. This purpose, the YWCA’s constitution declared, was to bring women to “such a knowledge of Jesus Christ as Saviour and Lord as shall mean for the individual young woman fullness of life and development of character.”4 The declaration, combining a Gospel paraphrase (“I have come that they might have life more abundantly” [John 10:10]) and the cadences of uplift, guided a pursuit of religious service that extended into the era of women’s liberation and liberation theology.

The YWCA’s persistent affirmation of the value of single-sex women’s organizations in shaping the public sphere can be credited with establishing a powerful infrastructure that pushed the organization’s members to connect the interpersonal to the political and the local to the global. The professional staff who steered the association’s operations and the members who participated in its programs brought to life what YWCA of the USA founder Grace Hoadley Dodge called “a spirit of womanhood and girls, a spirit of working together and being in touch with each other, trusting one another, with the loving Christ.”5 Religious mission dovetailed with dedication to gender separatism as the group blossomed into one of the largest and most diverse American women’s membership organizations in the early twentieth century. Its success should not be measured solely in numbers, however. For one thing, it should be marked in the reach of its programming. The YWCA became so robust that by the 1920s, four major (and still operating) organizations had been spun off from the parent group to focus on more specialized interests: Travelers Aid, which stationed matrons in transportation centers to intercept women travelers before they could be swindled or led astray; the International Migration Service, which aided refugee resettlement; the International Institute, an immigrant service provider; and an organization for career women, the Federation of Business and Professional Women.6 For another, the YWCA’s importance can also be gauged in the degree to which it fostered an international network of women intellectuals and activists. Finally, its influence can be apprehended in the visibility it achieved as an advocacy organization. The latter proved a source of contention. As this chapter concludes, although the YWCA’s roots as an evangelical women’s club initially warded off criticism of its religious politics, the association became ensnared in the Red Scare of the 1920s. As troublesome as charges of radicalism may have been, attacks on the YWCA denote the organization’s success. In ways that lone ministers, denominations, and single-issue interest groups could not, the YWCA brought an ethos of politically engaged Christianity to well over a thousand communities, campuses, and foreign missions. The ethos was rife with tensions: declarations of egalitarian fellowship were paired with considerable institutional segregation; democratic organizational procedures designed to empower minority constituencies were overseen by paternalistic administrators; and calls for social change favored moral suasion over confrontation. The tensions were ultimately productive, as the organization was persistently compelled to examine the disjuncture between its ideals and practices.

“The Kingdom of God in Its Fullness”

The executive staff and volunteers who operated the national organization at its founding drew on an organizational legacy that addressed two registers of the abundant life of the New Testament. Most important for the founders was the abundant life of salvation in the hereafter. Their programming continued in the vein of YWCA predecessor organizations, as YWCAs evangelized participants through a number of exclusively religious activities—including proselytization of the unchurched as well as worship and study for the devout. Yet the association had long been known for the variety of its offerings, reflected in the sprawling goals stated in its founding documents that aimed “to advance physical, social, intellectual, moral, and spiritual interests of young women.”7 Its work was accordingly very much directed at addressing the temporal realm. For the middle-class and affluent white clubwomen and professionals who made up most of the members of the volunteer committees and hired staff, social morality concerns served as a natural bridge between the call to evangelize and the drive to shape the public sphere.

Publicity material described the organization as “a great preventative and constructive agency,” “preventative because it offers to young women opportunities which lessen the power of temptations; constructive because in the all-round building up of character is being laid the foundations for the homes of the succeeding generations.”8 As a constructive agency, the YWCA offered all sorts of young women a salubrious path to self-development. Still, the group designated the evangelization of working women a favored category of work, which explains the emphasis on prevention—the prevention of moral ruin among women loosened from the controls of domesticity. YWCA leaders shared the preocc...