![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Change is everywhere; it is in every corner of our lives. From people wanting to lose weight and eat healthy; to families wanting to increase the quality of their interactions; to companies trying to become global, more responsive to customers, and include social networking in their business plans; to governments trying to reinvent themselves, we are becoming a world focused on change. Formally, change is defined as “to cause to be different.”1 Transformation, a similar word that people use to describe major changes, is defined as “a change or alternation especially a radical one.”2 It is the concept of producing a different and often radical result that is the focus of not only this book but also so many others that have come before and will probably come after. However, with all this focus on change, there is a lot of confusion about how to create successful change. Because change is so difficult, we find it useful to think of an analogy to help us understand change. For example, when a child asks a parent what love is, the parent begins an extended philosophical discussion over the origin, emotion, and meaning of love. On the other hand, the parent could use an analogy: The feeling of love is like the feeling you get when you are getting ready to listen to your favorite song; even though you know the song, it never gets boring. Or love is like the joy you get from seeing your favorite painting. We are using the analogy of a recipe to understand change, and more specifically, organizational change.

The power of an analogy can also be grounds for weakness. The topic of change, and organizational change more specifically, is complex, and we admit that transforming a 100,000-person workforce might be a bit more difficult than baking cakes and cupcakes (no matter how the reality television shows try to make baking seem like an extremely complicated task). We advise readers to take the applicable lessons, and we refrain from conducting an exhaustive analysis of the analogy. Look forward to gaining personal insights to increase your skills in creating and leading organizational transformation, even if it isn’t always exactly like baking a cake.

This book details five key ingredients for successful transformation programs. We say there is a recipe for change: When baking a cake, sugar is necessary, but so too are flour, eggs, milk, and butter. Before you start baking a cake, you want to make sure you have all the ingredients. We suggest the same thing for your change journey. Before you venture out on the path of major change, this book will make sure you have all the ingredients.

So how were these ingredients for successful change developed? These ingredients represent information gathered from an ongoing study of personal, relational, and organizational change that has lasted almost 50 years. We bring firsthand insights from our combined leadership experience inside a Fortune 100 company, university research centers at the top business and engineering schools in America and Canada, and consulting experience with numerous public and nonprofit organizations. We have worked with organizations ranging from HP, IBM, Intel, and Corning to the public sector of countries in Europe, North America, Africa, and Asia. Based on our extensive research on individual, relational, and organizational change methodologies, we have developed these five key ingredients that produce successful change. Our intention is for you to embed these ingredients into your change initiatives as foundation elements. In the midst of a complex and detailed plan, losing sight of the essential ingredients spells disaster.

The five ingredients for successful organizational change are the following:

- Vision. Where do you want to go?

- Leadership. Who is going to take you there?

- The technical plan. How will you get there?

- The social plan. How will you enroll others?

- The burning platform. Why leave where you are? What is compelling you to make any change at all? Or said another way, why are you leaving your current situation?

In chapter 2, we describe how transformation is different from other types of change efforts. In chapter 3, we describe why transformation is difficult. We also discuss how transformation needs to be approached systemically so that it addresses individuals, relationships, stakeholders, and tools and techniques.

In chapter 4, we discuss not only the importance of having a vision for transformation efforts but also how vision statements relate to mission statements and organizational values. We then provide some suggestions for how vision statements should be developed.

In chapter 5, we argue that transformational leaders need sufficient managerial and leadership skills. We do not view leadership as more important than management; instead, we argue that they are both complementary skills needed to be successful.

In our chapters on technical plans, we identify three key issues in developing a plan. Chapter 6 describes the need to identify the organizational gap between its current reality and its desired vision. This chapter also suggests how organizational leaders can decide which transformation technique, tool, or methodology to use to execute transformation. Chapter 7 provides a performance management system to manage transformational change efforts. Chapter 8 describes the importance of having a social plan in place to support your technical plan. Chapter 9 describes the purpose of having a sense of urgency, or burning platform, to provide both internal and external motivation for executing major transformation. We conclude the book by describing “the wall” as a tool to help leaders develop and communicate their transformation efforts.

At the end of each chapter, we provide a summary of the key lessons from the chapter, our key takeaways, and some action opportunities that you can take as you start your transformation journey.

![]()

Chapter 2

What Is Transformation?

What Is Change?

Hopefully, if you are picking up this book, you recognize that the world around you is changing almost faster than you can say “organizational change.” As a thought exercise, think of all the things you use and do every day that your grandparents did not have access to. For some, that might be a car; for others, a phone, television, and maybe access to education. Now think of things you use and do every day that your parents did not have access to: the Internet, color television, ATMs, and cell phones. How about things you use and do every day that even you didn’t use 4 or 5 years ago: Facebook, for instance, or text messages? Think about it: How many people actually get a check from their employer, walk over to a bank, and deposit it? So the issue really isn’t why organizations change; the issue is that the world is changing and organizations just have to keep up with it. We can only imagine how cheap a 3-D television will be by the time you are reading this book. Think about it: 3-D—something that only 5 years ago we would have thought can only be meant for large, expensive movie theaters—might become something that everybody has in their basement.

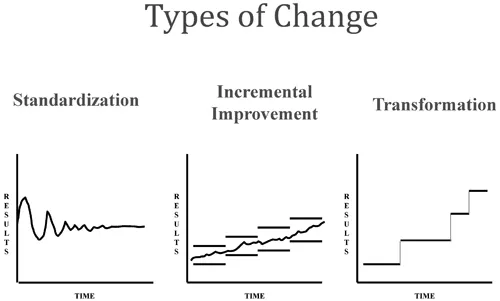

All change, however, is not the same in terms of magnitude or impact. We don’t need to change everyone in the entire organization, as well as all the systems and all the processes, if by change we just mean adjusting the temperature setting by 2 degrees. Similarly, we don’t suggest that if you are trying to lose 5 pounds you need to go through the same efforts to lose weight as someone trying to lose 25, 50, or even 200 pounds. While these examples are indeed change, we suggest the magnitude of the change dictates the effort needed to lead the change.

So for different types of changes, you will need different tools, approaches, and even language to lead the change. In the following sections, we describe three different approaches to change: standardization, incremental improvement, and transformation.

Types of Change

Changing a system to become better able to eliminate variation is known as standardization. Mapping out organizational processes and flows is part of creating standardization. When trying to standardize, training efforts are aimed at creating common approaches to work. The International Organization for Standards (ISO), as a standardization technique, works to develop standards in an ever increasing menu of fields of human endeavor. When we worked in manufacturing, our company used a concept called the “Key Elements for Safety.” These key elements helped standardize how we reported, addressed, and corrected safety issues in our manufacturing facilities. Furthermore, with healthy system definitions focused on the voice of the customer, performance management can be employed. The idea is rather simple and straightforward. Once organizational leaders understand what is required of them from their external customers, organizational leaders can now create practices and processes to meet, and potentially exceed, the requirement of the customer. Having the view of value streams needed to delight customers captured in system format, system owners can be assigned and help nurture both the internal processes and the system outcomes. So instead of having a job with a list of tasks unconnected to anything, people are engaged in a dynamic system with measureable outcomes, which when joined with other critical value streams results in delighting the customer. In short, standardization helps to reduce variation, thereby improving the overall performance and reliability of whatever result you want to produce.

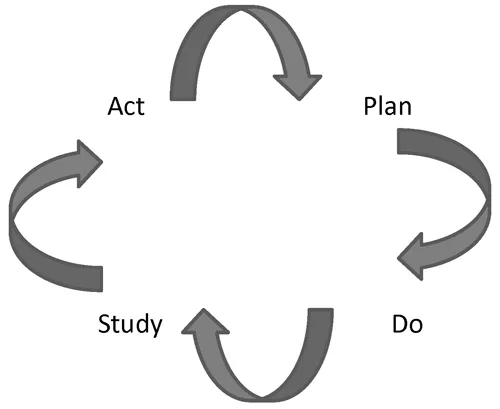

Incremental improvement is another type of change, which targets a shifting performance to a new, more desirable level. In a statistical sense, while standardization is about reducing variation, incremental improvement is about shifting the performance to a sustainable new plane. Incremental improvement entails a mind-set geared toward problem solving: determining root causes of inferior performance, converging on an answer or solution, and systematically implementing that solution. Incremental improvement methodologies are abundant and all follow a plan-do-study-act framework.1

The basic idea behind the plan-do-study-act framework is that you start with your plan. Where do you want to go? Then you actually do something: You implement the plan. Following the implementation, you review or study your results to determine if the actions you took created the desired results. Following your review, you then adjust your plans or act upon the results of your study. This cycle then starts over again with the re-creation or modification of your plan (see Figure 2.1).

Having established standardized systems with a focus on customer satisfaction, system owners can lead incremental improvements by addressing process enhancements. Incrementally improving the systems in concert with other value streams allows for the entire organizational results to improve. And with the system owners leading the incremental improvements, they are able to move the changes into standardization. Without this companion relationship between incremental improvement and standardization, improvements are lost and good ideas do not result in permanent system changes.

The third type of change involves breakthrough results, discontinuous change, and is brought about by redesign—that is, transformation. Transformational improvement is arguably the least understood yet the most critical type of change work. Here, the primary mental model is one of creation—bringing something into existence—and not simply making something like performance problems go away, as is the case with incremental improvement. Text messaging as a way of communication is an example of transformational change; it was not an incremental improvement over traditional methods of communicating. With breakthrough change, the aim is stepwise improvement. While we think the steps and suggestions in our book can help you lead all three types of change, our major focus will be on transformational improvement (see Figure 2.2).

Transformational thinking suspends focus on the current systems with an eye on the future to be created. In transformational thinking, a future is something to be created and not a problem to be solved. Using a greenfield or white paper approach, thinking isn’t saddled with the current problems. In this way, new and radical ideas are allowed to surface, giving way to transformation and breakthrough performance. Of course, the work then becomes moving the current situation toward the future vision with its new operational approaches.

The importance of transformational change has been highlighted in the wake of increasing technological and social change.2 In our combined world history, major transformation erupted as an occasional tsunami. The world was upended with major wars, noted inventions such as the printing press and cotton gin, and shifts in governance models. We could note these major, transformational changes on a timeline and even understand to a large degree the interdependency of the individual changes. But in today’s world, the tsunamis of change are rapidly hitting the shoreline. There is not enough time to absorb one tsunami before another one hits. And given that the world’s population has more than doubled since 1960, there are many more people creating change through both need and inventiveness. More change, composed of both social and technical facets, is overwhelming many people. But freezing in the face of major change doesn’t mean the wave coming toward the shore is going to stop.

So whereas standardization and incremental improvement were all well and good in the past, only interrupted by the occasional transformational change, all three work in our daily lives all the time. Be it the impact of satellite global positioning systems and communication, computerization of nearly everything, advances in energy sources or genome mapping, change is ubiquitous. Developing skills, passion, and an appetite for leading transformational change is now a requirement in our lives, families, teams, and organizations.

An example comes to mind. Imagine 200 years ago. What advice would a mother and father give their children as those children became mothers and fathers? Something about working the land as a farmer or hunter? Something about “old wives” remedies for sicknesses? Maybe some advice about how a father should behave or about the advice that a father should impart to his children? Our guess is that the transmission of parental advice was fairly stable across many generations over the previous 200 years. Now think about the advice your parents might have given you with respect to how to raise your children. If your children are like ours, they are involved in way too many activities; the only way we can communicate with them is via text messages, and we spend most of our quality time together in the car. What happened? A tsunami of change has descended on the family unit in terms of social changes, cultural changes, and technological changes. We are not at all implying the advice our parents gave us is now all wrong (that is why it is called wisdom), but we are suggesting that changes are all around us, and successful individuals (e.g., leaders of organizations, coaches of sports teams, and even parents of children) need to develop skills to cope and lead the changes. What can make this frustrating is that often the skills to lead change are developed at the same time as the change itself is being implemented. (Think about how parents had to figure out the acceptable use of text messages at the same time that their children were starting to use text messaging.)

More broadly, it is difficult to accomplish transformational change resulting in an expected outco...