- 255 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Strategic Management

About this book

Organizational success crucially depends on having a superior strategy and effectively implementing it. Companies that outperform their rivals typically have a better grasp of what customers value, who their competitors are, and how they can create an enduring competitive advantage. Successful strategies re ect a solid grasp of relevant forces in the external and competitive environment, a clear strategic intent, and a deep understanding of a company's core competencies and assets. Generic strategies rarely propel a rm to a leadership position. Knowing where to go and nding carefully considered, creative ways of getting there are the hallmarks of successful strategy.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

What Is Strategy?

Introduction

The question “What is strategy?” has stimulated lots of debates, countless articles, and serious disagreement among management thinkers. Perhaps this is why many executives also struggle with it. However, they deserve a pragmatic reply. Understanding how a strategy is crafted is important, because there is a proven link between a company’s strategic choices and its long-term performance. Successful companies typically have a better grasp of customers’ wants and needs, their competitors’ strengths and weaknesses, and how they can create value for all stakeholders. Successful strategies reflect a company’s clear strategic intent and a deep understanding of its core competencies and assets—generic strategies rarely propel a company to a leadership position.

Numerous attempts have been made at providing a simple, descriptive definition of strategy but its inherent complexity and subtlety preclude a one-sentence description. There is a substantial agreement about its principal dimensions, however. Strategy is about positioning an organization for competitive advantage. It involves making choices about which markets to participate in, what products and services to offer, and how to allocate corporate resources. And its primary goal is to create long-term value for shareholders and other stakeholders by providing customer value. Strategy therefore is different from vision, mission, goals, priorities, and plans. It is the result of choices executives make, about what to offer, where to play and how to win, to maximize long-term value.

What to offer refers to a company’s value proposition and comprises the core of its business model; it includes everything it offers its customers in a specific market or segment. This comprises not only the company’s bundles of products and services but also how it differentiates itself from its competitors. A value proposition therefore consists of the full range of tangible and intangible benefits a company provides to its customers and other stakeholders.

Where to play specifies the target markets in terms of the customers and the needs to be served. The best way to define a target market is highly situational. It can be defined in any number of ways, such as by where the target customers are (for example, in certain parts of the world or in particular parts of town), how they buy (perhaps through specific channels), who they are (their particular demographics and other innate characteristics), when they buy (for example, on particular occasions), what they buy (for instance, are they price buyers or do they place more value on service?), and for whom they buy (themselves, friends, family, their company, or their customers?).

How to win spells out the capabilities and policies that will give a company an essential advantage over key competitors in delivering the value proposition. As such, it has two dimensions. The first is the value chain infrastructure dimension. It deals with questions such as: What key internal resources and capabilities has the company created to support the chosen value proposition and target markets? What partner network has it assembled to support the business model? and How are these activities organized into an overall, coherent value creation and delivery model? The second is the management dimension. It summarizes a company’s choices about its organizational structure, financial structure, and management policies. Organization and management style are closely linked. In companies that are organized primarily around product divisions management is often highly centralized. In contrast, companies operating with a more geographic organizational structure usually are managed on a more decentralized basis.

Choices must be made because there is usually more than one way to win in every market, but not everyone can win in any given market. With good choices, a business gains the right to win in its target markets. The target market, value proposition, capabilities and management regime must hang together in a coherent way.

Most companies face innumerable options for what value proposition to choose, where to play and how to win. As well, they have to sort out seemingly conflicting objectives such as the need for both long-term growth and short-term profitability. To “maximize long-term value” means—when there are mutually exclusive options—to select options that will give the greatest sustained increase to the company’s economic value. It is worth emphasizing that “maximizing long-term value” is not the same thing as “maximizing share price” or “maximizing shareholder value.” Those objectives typically represent the more short-term demands of current shareholders or their advisers, and they do not always align with what is best for all stakeholders, On the other hand, “maximizing long-term value” does not mean forgetting about the short term. Economic value takes into account growth and profitability, the short term and long term, and risk as well as reward.

Strategic thinking has evolved substantially in the past 25 years. We have learned much about how to analyze the competitive environment, define a sustainable position, develop competitive and corporate advantages, and how to sustain advantage in the face of competitive challenges and threats. Different approaches—including industrial organization theory, the resource-based view, dynamic capabilities and game theory—have helped academicians and practitioners understand the dynamics of competition and develop recommendations about how firms should define their competitive and corporate strategies. But drivers such as globalization and technological change continue to profoundly change the competitive game. The fastest growing firms in this new environment appear to be those that have taken advantage of these structural changes to innovate in their business models so they can compete differently.

In addition to the business model innovation drivers noted above, much recent interest has come from three other environmental shifts. Advances in information technology have been a major force behind the recent interest in business model innovation. Many e-businesses are based on new business models. New strategies for the ‘bottom of the pyramid’ in emerging markets have also steered researchers and practitioners toward the systematic study of business approaches. Third, the quest for sustainability and commitment to corporate social responsibility in all aspects of a business have become an imperative: A company that creates profit for its shareholders while protecting the environment and improving the lives of those with whom it interacts is likely to enjoy a significant competitive advantage over its rivals. These companies operate in such a way that their business interests and the interests of the environment and society intersect.

The evolution of strategic thinking reflects these changes and is characterized by a gradual shift in focus from an industrial economics to a resource-based perspective to a human and intellectual capital perspective. It is important to understand the reasons underlying this evolution, because they reflect a changing view of what strategy is and how it is crafted.

The early industrial economics perspective held that environmental influences—particularly those that shape industry structure—were the primary determinants of a company’s success. The competitive environment was thought to impose pressures and constraints, which made certain strategies more attractive than others. Carefully choosing where to compete—selecting the most attractive industries or industry segments—and control strategically important resources, such as financial capital, became the dominant themes of strategy development at both the business unit and corporate levels. The focus, therefore, was on capturing economic value through adept positioning. Thus, industry analysis, competitor analysis, segmentation, positioning, and strategic planning became the most important tools for analyzing strategic opportunity.1

As globalization, the technology revolution, and other major environmental forces picked up speed and radically changed the competitive landscape, key assumptions underlying the industrial economics model came under scrutiny. Should the competitive environment be treated as a constraint on strategy formulation, or was strategy really about shaping competitive conditions? Was the assumption that businesses should control most of the relevant strategic resources needed to compete still applicable? Were strategic resources really as mobile as the traditional model assumed, and was the advantage associated with owning particular resources and competencies therefore necessarily short lived?

In response to these questions, a resource-based perspective of strategy development emerged. Rather than focusing on positioning a company within environment-dictated constraints, this new school of thought defined strategic thinking in terms of building core capabilities that transcend the boundaries of traditional business units. It focused on creating corporate portfolios around core businesses and on adopting goals and processes aimed at enhancing core competencies.2 This new paradigm reflected a shift in emphasis from capturing economic value to creating value through the development and nurturing of key resources and capabilities.

The current focus on knowledge and human and intellectual capital as a company’s key strategic resource is a natural extension of the resource-based view of strategy and fits with the transition of global commerce to a knowledge-based economy. For a majority of companies, access to physical or financial resources no longer is an impediment to growth or opportunity; not having the right people or knowledge has become the limiting factor. Microsoft, Google, and Yahoo scan the entire pool of U.S. computer science graduates every year to identify and attract the few they want to attract. Today it is recognized that competency-based strategies are dependent on people, that scarce knowledge and expertise drive product development, and that personal relationships with clients are critical to market responsiveness.3

Strategy Formulation: Concepts and Dimensions

Strategy, Business Models, and Tactics

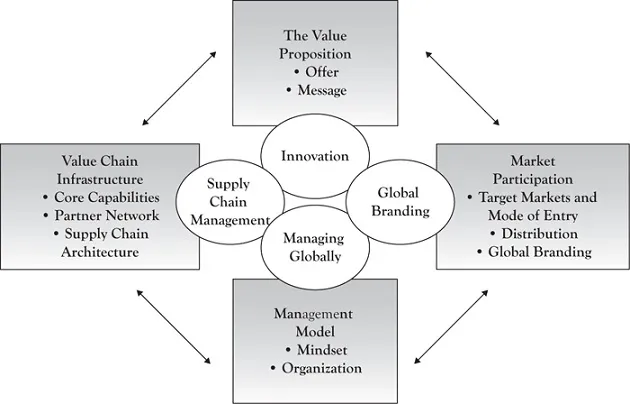

Every company has a business model—a blueprint of how it does business—defined by its core strategy although it may not always be explicitly articulated. This model most likely evolved over time as the company rose to prominence in its primary markets and reflects key choices about what value it provides to whom, how, and at what price and cost. As shown in Figure 1.1, it describes who its customers are, how it reaches them and relates to them (market participation); what a company offers its customers (the value proposition); with what resources, activities, and partners it creates its offerings (value chain infrastructure); and finally, how it organizes, finances, and manages its operations (management model ).

A company’s value proposition comprises the core of its business model; it includes everything it offers to its customers in a specific market or segment. This comprises not only the company’s bundles of products and services, but also how it differentiates itself from its competitors. A value proposition therefore consists of the full range of tangible and intangible benefits a company provides to its customers and other stakeholders.

Figure 1.1 Four components of a business model

The market participation dimension of a business model has three components. It describes what specific markets or segments a company chooses to serve, domestically or abroad; what methods of distribution it uses to reach its customers; and how it promotes and advertises its value proposition to its target customers.

The value chain infrastructure dimension of the business model deals with such questions as: What key internal resources and capabilities has the company created to support the chosen value proposition and target markets? What partner network has it assembled to support the business model? and How are these activities organized into an overall, coherent value creation and delivery model?

The management submodel summarizes a company’s choices about a suitable organizational structure, financial structure, and management policies. Typically, organization and management are closely linked. In companies that are organized primarily around product divisions management is often highly centralized. In contrast, companies operating with a more geographic organizational structure usually are managed on a more decentralized basis.

Business models can take many forms. The well-known “razor–razor blade model” involves pricing razors inexpensively, but aggressively marking-up the consumables (razor blades). Jet engines for commercial aircraft are priced the same way—manufacturers know that engines are long lived, and maintenance and parts are where Rolls Royce, General Electric (GE), Pratt & Whitney and others make their money. In the sports apparel business, sponsorship is a key component of today’s business models. Nike, Adidas, Reebok, and others sponsor football and soccer clubs and teams, providing kit and sponsorship dollars as well as royalty streams from the sale of replica products.

In industries characterized by a single dominant business model competitive advantage is won mainly through better execution, more efficient processes, lean organizations, and product innovation. Increasingly, however, industries feature multiple- and co-existing business models. In this environment, competitive advantage is achieved by creating focused and innovative business models. Consider the airline, music, telecom or banking industries. In each one there are different business models competing against each other. For example, in the airline industry there are the traditional flag carriers, the low-cost airlines, the business class only airlines, and the fractional private jet ownership companies. Each business model embodies a different approach to achieving a competitive advantage.

Describing a company’s strategy in terms of its business model allows explicit consideration of the logic or architecture of each component and its relationship to others as a set of designed choices that can be changed. Thus, thinking holistically about every component of the business model—and systematically challenging orthodoxies within these components—significantly extends the scope for innovation and improves the chances of building a sustainable competitive advantage.

The term “strategy”, however, has a broader meaning. It extends beyond the d...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Chapter 1 What Is Strategy?

- Chapter 2 Strategy and Performance

- Chapter 3 Analyzing the External Strategic Environment

- Chapter 4 Analyzing an Industry

- Chapter 5 Analyzing a Company’s Strategic Resource Base

- Chapter 6 Formulating Business Unit Strategy

- Chapter 7 Business Unit Strategy: Contexts and Special Dimensions

- Chapter 8 Global Strategy: Fundamentals

- Chapter 9 Global Strategy: Adapting the Business Model

- Chapter 10 The Board’s Role in Strategic Management

- Notes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Strategic Management by Cornelius de Kluyver, John A. Pearce in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Strategy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.