![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Confusion

It was January 17, 2010. I was a U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel, in charge of a logistics support battalion. I had deployed to Port-au-Prince, Haiti to provide assistance and relief from the earthquake that had occurred several days before. Prior to departing, I visited an old mentor, Colonel Duane Gamble, who was currently serving as the XVIII Airborne Corps G4, the chief staff officer for logistics, at my home base, Fort Bragg, North Carolina. I asked him what he thought our mission would be in Haiti. “To clear the ports,” he replied. I left his office not knowing fully what he meant.

After arriving at the Port-au-Prince airport, I quickly realized what he had meant. Relief supplies in the form of generators, medical supplies, and tents were quickly piling up just off the airport’s main runway. When I asked who was in charge of distributing these items, I was directed to a young leader from the World Food Program. I approached her and offered to distribute the supplies with the trucks our battalion had on the ground. She tersely replied, “You’re not one of our customers,” and that was the end of the conversation as she turned around and took a call on her cell phone. Dumbfounded, I would not understand her response until 18 months later, while taking a class on Emergency Management at North Dakota State University. In the meantime, while our battalion established a substantial amount of distribution capacity over the next 30 days, I could not understand why 90 percent of our missions during our 75-day deployment to Haiti would be to support U.S. soldiers and not relief victims.

Not that supporting the soldiers of the 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 82nd Airborne Division was a simple task. While some required items were pushed to us, we had to request others, and the resupply results were largely unpredictable. Additionally, our requirements for maintenance and repair parts for vehicles, generators, trailers, and other equipment began to grow with our time on the ground, and most of these parts had to be requested from sources within the United States, leaving our equipment inoperable during the wait time. About 10 days into the operation, I visited Colonel Gamble again to discuss establishing some predictability to our resupply methods. Colonel Gamble had deployed early in the operation and had assumed the role of the senior staff logistician for Joint Task Force Haiti. He asked me a simple question, “Have you established a demand signal?” He was referring to our battalion’s ability to electronically submit requisitions upstream to the wholesale supply system of the Department of Defense. As it so happened, we were in the process of doing so and completed the connection the following day, on January 27, 2010. Once we established this ability to submit requisitions electronically, we no longer had to call for or e-mail our requirements.

For reasons I didn’t fully understand, establishing this automated requisitioning ability was somewhat difficult, and had been so throughout my career. It certainly wasn’t a seamless, instantaneous process. In 2003, when deploying to Iraq on short notice, it required nearly 60 days to establish this system. In 2005, when deploying to New Orleans, also on short notice, it took 30 days. So, while establishing it in 10 days seemed certainly to be an improvement, I still wondered about the impact not establishing it sooner had on our resupply system and the readiness of our customer, the 2nd Brigade Combat Team.

Around the same time, the Joint Task Force planned and executed Operation Flood, a large-scale distribution of 25 kg bags of rice to the population of Port-au-Prince. Under the supervision of local authorities, host nation trucks moved bags of rice from a warehouse to another staging location, then to 15 distribution points across Port-au-Prince. Each distribution point was secured by a unit from 2nd Brigade and a coalition partner, and a Nongovernmental Organization (NGO) conducted the actual distribution.

I was puzzled by several aspects of the operation. Visiting the warehouse, I found it filled to the roof with bags of rice and didn’t understand why our battalion couldn’t have distributed them several weeks earlier, after the earthquake had hit. Apparently the World Food Program had staged the warehouse several months earlier, in anticipation of a hurricane that never occurred. I was also disappointed about the lack of involvement we had in the operation. While we put teams at the staging base, it was more to track progress than direct it. Moreover, while we had sufficient transportation assets to perform distribution for the entire operation, host nation drivers and trucks performed this mission instead. Our contribution to the operation was a “Quick Reaction Force”—a dedicated team of drivers with a contingency stock of rice that we dispatched several times upon receiving calls from the security teams at distribution points, concerned that they were running short of stocks and security would become a concern as a result.

Our battalion’s lack of involvement in Operation Flood was indicative of our overall contribution to disaster relief distribution during our time in Haiti over the next several months. Each night we reviewed our transportation asset utilization, and rarely did we find it exceeding 60 percent. I had a hard time understanding why NGOs would pay for local transportation while we possessed the required capacity. While we were able to perform a few disaster relief distribution missions, overall 90 percent of our distribution missions during Operation Unified Response (OUR) were in support of our own Brigade Combat Team.

Although I had previously deployed in support of other no-notice, rapid response situations, only after dedicated study and research did I understand that I had experienced some of the complexity involved in emergency supply chains.

Complexity

“Being complex is different from being complicated. Things that are complicated may have many parts, but those parts are joined, one to the next, in relatively simple ways: one cog turns, causing the next one to turn as well, and so on. The workings of a complicated device like an internal combustion engine might be confusing, but they ultimately can be broken down into a series of neat and tidy deterministic relationships; by the end, you will be able to predict with relative certainty what will happen when one part of the device is activated or altered. Complexity, on the other hand, occurs when the number of interactions between components increases dramatically.”

—GEN (R) Stanley McChrystal1

Complex systems are defined by a variability so great that modeling, predicting, or even understanding the system becomes extremely difficult. By this view, while conventional commercial supply chains may be complicated, emergency supply chains are inherently complex due to their inherent variability. Emergency supply chains involve a different customer, different place, different sustainment requirements, different infrastructure, and different stakeholders.

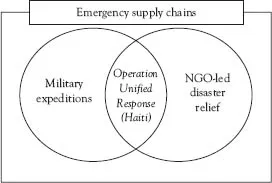

Operation Unified Response was arguably one of the more complex examples of an Emergency Supply Chain, where the two domains of emergency supply chains coincide: the domain of a military no-notice expedition, and the domain of NGO-led disaster relief effort. Figure 1.1 depicts the relationship between these two domains within the framework of emergency supply chains and where OUR fell in-between.

Figure 1.1 Operation Unified Response within the emergency supply chain framework

In a very short time, without even awareness of what was really occurring, we had experienced several key sources of complexity which characterize such an environment:

Across the two domains, multiple actors with different perspectives, objectives, funding methods, and means of measuring success

Between the two domains, fundamental misunderstanding and conflict of roles and responsibilities between military and NGOs in disaster relief

Within both domains, a reliance on manual requisitioning and reporting systems

Within the disaster relief domain, the nature of assessing disaster relief victim demand

Within the military domain, reconciling the difference between predeployment and deployed demand

Supply chains supporting military expeditions are complex. Born out of the emergency prompting the expeditionary deployment, they require military units to deploy to a new environment and an accompanying new demand from their home station environment. Reconciling the difference between these two demand patterns is difficult, as requisitions are passed and accommodated using a manual system.

Disaster relief supply chains are even more complex. By responding to an emergency, they also lack a developed forecast, primarily use manual requisitioning systems, and do not possess sophisticated means to sense and respond to the emerging demand. Multiple stakeholders come together, many for the first time, to execute “on the fly.”

The various sources of complexity can be viewed and understood as threats to the emergency supply chain’s ability to effectively sense, and respond to, demand within the emergency environment. In this context, the term “sense and respond” refers to a supply chain’s ability to detect demand requirements and meet them in a manner that contributes to the overall desired effect of the emergency operation.

Within emergency supply chains, achieving this desired effect, either in preserving combat capability or providing relief, defines success. As a result, the primary focus becomes getting the job accomplished “at all costs”; supply chain efficiency becomes an afterthought, and optimization is difficult if not undesired. Due to their infrequent nature, less has been written and studied in the area of emergency supply chains, increasing the risk that those practitioners supporting the next emergency operation will encounter the same difficulties.

This Book’s Relevance

The overall purpose of this book is to describe the complexity of emergency supply chains, as logistics and supply chains throughout military and disaster relief research have been recognized as key to conducting these operations.2 Without supplies, the majority of relief efforts quickly lose relevance and value.3 Military operations have shown that while deploying forces under emergency conditions is difficult, sustaining these forces is absolutely imperative to the operation’s success.4

Yet, misunderstanding the complexity of emergency supply chains is likely quite common. While expeditionary and rapid response missions are a desired capability throughout U.S. military forces, the preponderance of forces do not experience such operations. The amount of military expeditions over the last 15 years pales in comparison to the number of personnel who have participated in deliberate combat operations in Operation Iraq Freedom (OIF), Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), and Operation New Dawn (OND).5

Further, focusing military organizations on disaster relief operations may not be a priority. Although the U.S. Army’s sustainment vision of the future6 depicts a Haiti-style relief model of worldwide rapid deployment, it is not practiced as often as Direct Action Training Exercises (DATE) at Combat Training Centers. Along with training, the Army may lack the doctrine and the supporting lessons learned to fully understand emergency environments. The Army’s picture of the sustaining future relies heavily on the ability to establish automated systems during expeditionary operations, referring to Operation Unified Response as an operational model;7 the majority of military literature largely lacks specificity of the employment and establishment of an automated logistics network, as well as a quantifiable analysis to support the network’s utility. Army regulations largely discuss procedures for building stocks in established theaters but are sparse in addressing methods for doing so under immature conditions. The literature that does exist remains compartmentalized within the sustainment doctrine, as opposed to being embedded in the operational doctrine. Additionally, a search of over 300 articles from the Army’s Center for Army Lessons Learned database (CALL) revealed no discussion on the challenges involved in establishing the automated requisitioning system for 2nd Brigade, 82nd Airborne Division during Operation Unified Response.

At the same time, there is an enduring need to understand disaster relief operations by multiple communities. Research supports that the number, magnitude, and accompanying disaster situations will increase,8 which will in turn require an enhanced response capability from those executing disaster supply chains.9 However, while the frequency of disaster relief operations is on the rise, there is not necessarily a corresponding increase in the capture, synthesis, and sharing of knowledge within the disaster relief operations community, as well as among the military, commercial, industry, multinational, government, and academic circles. This disconnect may contribute to a common misunderstanding of disaster relief supply chains, their relationship with military expedition supply chains, and the holistic complexity involved in emergency supply chain situations.

Who This Book Is for

It is for the reasons stated in the preceding section that this book, Understanding the Complexity of Emergency Supply Chains, seeks to comple...