![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Bottom Line: The Real Deal on Inclusion

We say we want inclusion but what if we really don’t?

We work at being inclusive, but we never quite arrive. Perhaps we have unconscious beliefs at odds with what we say we want—a hidden agenda that deters and detracts from our consciously stated desires.

Inclusion is complex. It is in our human nature not to be liberally inclusive or, at the very least, to be skeptical of it. The challenges of inclusion arise from human problems that come from human situations and have to be explored in a human way. Inclusion is not merely a program to be implemented; it is an inherently human characteristic with many complex variables, twists, and turns. That is why it is probable we are not really trying to be inclusive; we only think we are.

Selfishness and Altruism—The Odd Couple

What does inclusivity look like? What do I mean by selfishness as it relates to inclusion? What does altruism have to do with inclusion?

My vision of inclusivity does not include all of us being inclusive all of the time. It is a more measured and realistic look at what is possible. It is an ability to be more open to inclusivity while at the same time more fully understanding the parameters and boundaries that limit us. Pragmatically speaking, perhaps we don’t really understand what inclusivity is and the sacrifices it entails. We don’t have a firm grasp on what it could look like and maybe are not hard-wired to be inclusive. Despite the humor, the old adage, “Ok enough about me, why don’t you talk about me now?” holds more than a grain of truth. We are inherently selfish. Yet we can be led toward altruism. Altruism is defined as the disinterested and self-less concern for the well-being of others. When I think about altruism, Mother Teresa comes to mind, but most of us don’t even get close to that standard.

But altruism is actually not part of the equation when we strive to be more inclusive at work. Inclusion programs at work are driven by the desire to improve team work, productivity, creativity, innovation and profit and subsequently reap an improved Return on Investment (ROI) for the company. And while we individually have the potential to be altruistic, we are actually predisposed to be selfish; to think about ourselves first, to relate everything back to ourselves and seek to protect ourselves and our territory. A few years ago one of my clients moved from a hierarchical management system to empowered work teams. As part of that change, they opened an activity-based building where employees were expected to work on a hot-desking system, without their own defined workspace. However, people quickly claimed their favorite space and brought personal artifacts from home to mark their territory. Many meetings over many months were needed to educate people not to mark their own lamp post.

Why does it take us so long to change, even when we say we want to? Our brain habituates. It is much more comfortable finding patterns, making sense of them, and sticking to them. Our unconscious brain processes 200,000 times more information than the conscious mind and is constantly looking for patterns. When it finds them, it wires them together; this is a process of which we are not consciously aware (Jones and Cornish 2015). These patterns, red flags, and conflicting feelings permeate our unconscious. In addition, our invisible “rules for inclusion” show up in many ways both at home and work. We can be well-meaning and work diligently toward creating a more inclusive workplace and yet fail to achieve our stated goals. In large part, this is because our internal programming is designed to be selective and cautious about whom we let in to our inner circle and on what terms they can join.

Speaking of patterns, I have found most people do not feel comfortable with the idea they may be to blame for any form of discrimination toward others; often separating in their minds how they show up at work with their professional faces from how they show up in the privacy of their own homes and communities. At a recent dinner party I overheard one of the dinner guests saying “The Blacks in this country should be grateful; they don’t know how good they’ve got it.” My eyebrows shot up as I leaned forward to listen intently, eventually intervening with my own perspective. The people talking believed they were decent people and good neighbors, who were not prejudiced. In their defense, one of them was quick to say that they have Black neighbors and another that her new grand-daughter has a Black father, as if those explanations gave them permission to fragment their thinking and exempted them from bias.

The views expressed at the dinner party are not isolated, unique, or limited to one group. It is part of the human condition and the issues of inclusion and exclusion run deep. And I am sure you can somehow relate to this story. We all have many sides to our personalities and many different faces we show to the world.

Dr. Peter Jones, a Professor at Cambridge University Neuro Science Department (Jones and Cornish 2015) said, even if you consciously reject a stereotype, it will lie dormant in neural pathways waiting to be activated; just like data sits on your hard drive waiting to be accessed. For instance, it’s a safe bet when you were a child, your parents told you to forget about something biased you heard. Try as you might, the message was already received and dropped into the neural pathways, lying dormant waiting for opportunities to remind you of it. We take in mind viruses and form mental models of people and situations without realizing it. In fact, Dr. Jones says that frequently using a particular cognitive pathway increases the likelihood it will get used again. This is done by coating the nerve ending with a substance called myelin, which increases the efficiency of activation of that route by up to 5,000 times. Just seeing or hearing a stereotype increases the myelination even if you consciously reject it. Your brain is lazy and always likes to have the complete picture. If the information is missing, it will seek to fill it with the most likely fit. Your biases are often used to fill in the gaps. My friends at the dinner party were able to convince themselves of their inherent goodness and tolerance, while unconsciously tapping into those knotty, or do I mean naughty, myelinated messages. Assumptions of affinity and shared values were under pinning the conversation at the dinner party in question. While they cannot be removed, you can learn to catch them and be mindful of the choices you make going forward.

Sometimes we assume as we look around the room that we have affinity with others, without knowing their unique story. Often, the speaker does not give any thought to the pain caused by throwaway comments and do not realize their words might be hurting others. We see a group that “looks like us,” and we unconsciously assume shared values. We may not know that someone’s son is gay or married to someone from another culture. We see someone who looks White, but they are really Latino or Black. Comments are made about members of different groups or people’s characteristics (height, weight, and so on) with the implicit assumption that everyone in the assembled gathering agrees. Frequently that is not the case and as the old adage says, “Once the words are out of your mouth, they are out of your control.”

A UCLA study by Naomi Eisenberger and Matthew Lieberman discovered that the part of the brain that experiences pain when you cut your finger is the same part activated and agitated when you feel excluded. They hooked a student up to a Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging machine (fMRI) and had him take part in a computer simulation game throwing the ball to two other people. After about 10 minutes of inclusion in this exercise he was then excluded, and was never thrown the ball again. The act of being excluded showed up in his brain patterns as a physiological reaction (Eisenberger, Lieberman, and Williams 2003). The study further concluded that taking a painkiller minimized the pain of exclusion just as it reduces the pain when you cut your finger. I am not recommending you do that however, it explains how being excluded is painful to the individual and a productivity drain on the organization.

Self-Sabotage—An Unconscious Plan for Failure and the Protection of the Status Quo

When we talk about being inclusive of difference, do we really act like this is something we want—or is it just something we think we should do? Do we unconsciously sabotage it because, in our hearts, the effort is too much? Are we dubious as to whether it is even possible? We are driven by the desire to be in relationship with others, but we consciously and unconsciously work to surround ourselves with people who share our values, beliefs, and behaviors that make us comfortable. In other words, we are only really comfortable including people who are either like us or are willing to do what it takes to fit in with us.

You may work in a diverse team, and you may be able to look around the organization and visibly see diverse people, but can you swear you know and understand all of their individual differences and underlying stories? Do you really, deep down, want to know more about diversity?

Over the years, many well-meaning leaders have told me they do not care about a person’s diversity, so long as they can do the job. They do not take the time to know their story. They do not care if they are purple with polka dots, so long as they can do the job. On these occasions, I ask, “But what if they care?” What if it matters to them and they would feel more able to be productive at work if they felt you understood their background?

There are a myriad of ways to send a message to your team you are not interested in who they are or what they have to say. These micro-messages are heard loud and clear not just by the individual concerned, but the entire team witnessing the exchange.

We unconsciously protect our territory and the status quo by shutting out other voices and styles. If we let them in, we might have to listen to them. We might have to adopt different ways of doing things; listen to different music, dance to a different tune, and eat different food. Are you really OK encouraging diverse voices, listening to diverse views and opinions, and implementing other ideas instead of your own?

I worked a few years ago with a client who was implementing an internal diversity awareness workshop based on the Diversity Onion or Diversity Wheel. The inner core of the onion contains social identity groups such as race, culture, gender, sexual orientation, age, and so on; the second circle contains issues such as family status, religious beliefs, marital status, military service, personality types, and so on; and the outer rim contains business issues such as functional groups, length of service, geographical location, and so on.

During a discussion with the training team about the impact of the workshop, a woman of color shared that she and her colleagues attended the workshop hoping they would finally have their voices heard. However, they found the facilitators were teaching the workshop from the outer rim of the Diversity Dimension model with only an occasional sojourn into the second circle and never ever putting their toes into the deeper waters at the core of the model where race, culture, gender, sexual orientation, and age lived.

She expressed disappointment that she and her colleagues were not able to share what it means to be a person of color at work. The message this sent to the participants was deafening.

The facilitators’ personal need to stay within their own comfort level and the unconscious collusion of many of the participants ensured the conversation stayed at a safe and superficial level. The outcome was that diverse views were not heard and differing opinions were not encouraged. Comfort and the status quo were maintained, ironically while still posturing as a Diversity and Inclusion initiative.

On another occasion, I observed a gay White male facilitator completely bypass a comment from an African American woman, ostensibly in the interests of moving on with the agenda. She raised her hand and shared that she felt isolated in the organization and was often the only Black person in a meeting. The facilitator thanked her and said, “That is interesting” and moved to the next topic. Her eyes got wide and she dropped her head in a slump of resignation and disappointment. There it is again, our inability to stay in the moment, hold someone’s gaze, and try to understand the depth of what they are saying. These are not isolated incidents. We are all capable of doing this and stories abound as to the many ways we can “move on” and select not to see or hear an opinion different from our own, particularly if it makes us feel anxious or fearful. If you do not believe me, think about your significant relationships at home. How often do you anticipate what your partner or spouse is about to say? How often do you cut them off at the pass or mentally roll your eyes and stop listening?

We want to do well, but we are often blinded by the light of our own intrinsic biases, while, at the same time, believing it is not us causing the lack of progress. The problem remains; if we are all being “well-intentioned” and telling ourselves it is not us, who is it?

Protecting Our Turf and Checking the Box

Why are we not achieving our stated goal? Why have we not closed the gender gap? Why are women and people of color not moving up the corporate ladder in significant numbers? Why do we have such a long journey ahead of us to get some diverse groups onto the leadership radar screen? Organizations pour money and resources into Diversity and Inclusion initiatives, and yet many companies are still spinning their wheels around the inclusion axis.

The crux of the problem is we don’t begin to appreciate the layers of convolution. We don’t always realize when we are not being inclusive. While it is part of human nature to want to be in relationship with others, inclusivity does not come naturally. It is not intuitive to accommodate differences. For example, we marry people for their difference and then spend the rest of the relationship trying to change them to be more like us. Companies do the same as they hire for diversity and manage for similarity. We fill our departments with diverse people, but never fully utilize their uniqueness. In fact, we directly and indirectly influence and acculturate them to minimize their differences in order to fit in. People of difference are complicit in this process as they want to belong, so we are all accomplices to the process that keeps us stuck. We may believe that we are being inclusive and genuinely not see or understand how much accommodation other people are making to ensure we are comfortable. Women, for example, are told to be more assertive, and are often sent to assertiveness training but, when they comply and try out their new found assertiveness, they run the risk of being labeled too aggressive or with other less flattering labels.

In many ways, we are checking the box to say we have done something while simultaneously maintaining the status quo; protecting our turf and maintaining our comfort levels.

How many managers do you know who are excellent listeners, who consciously work to ensure everyone’s voice is heard, who point out to the group when someone is interrupted or when someone takes another person’s ideas and claims them as their own? You might be tempted to proclaim, “But this happens to everyone and has nothing to do with diversity and inclusion”; but it does. Part of being inclusive is about how you treat people. The business meeting agenda may be the object of our attention, but people roll their eyes in meetings and gossip outside of meetings because of how they get treated and how they see others treated.

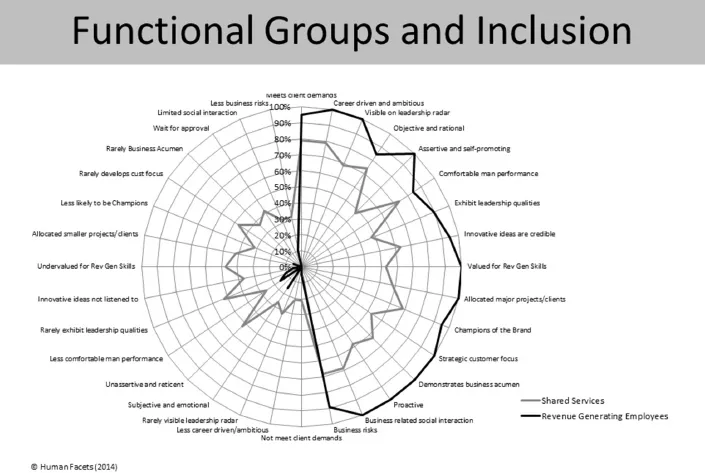

While it is spot-on that these things can happen to anyone, stories abound from women and people of color within organizations who know their voices are not heard as credible. The problem is more systemic and chronic than just a few people not being heard. Global research results from my unconscious bias assessment tool, Cognizant, show a consistently wide gap between dominant culture groups and subcultural groups on the issue of whose voice is heard as credible and whose ideas are more likely to be implemented. The example on this chart is only looking at the functional differences between revenue generating employees and support staff, but similar gaps exist in gender, race, culture, sexual orientation, and so on. Why does that happen if we say we want to be inclusive? Why does it happen if your team is already diverse? It happens because we lean toward affinity bias, and the status quo, and also because we are not always aware of what we are doing.

I had lunch with someone recently and every time I agreed with what she was saying, she emphatically proclaimed “No, no no; really, I am serious.” I was quite startled when she first did it as I was actually agreeing with her. But, as she continued to manifest that behavior I became used to it; anticipated it and later speculated that her job as a school teacher may have unconsciously influenced her to need to keep reinforcing her point with the students. Of course, I really don’t know why she does it and maybe one day I will ask her.

These anecdotal examples of understanding differences and being inclusive illustrate that it is more challenging and complicated than it first appears. Do we really know when we get it right or when we offend? Are we aware when we are holding back and avoiding conversations about differences? Do we really want to know the other person’s story, particularly if it might clash with the story we have in our head? Do we render diverse individuals who become our friends as phenomenological exceptions and yet still have challenges with their diverse group? Does all of this complexity make us opt for political correctness? Do we save our bias conversations until we are with close friends and/or people we assume will have affinity with us?

Over the years of working on Diversity and Inclusion, I have witnessed countless situations and heard numerous stories confirming that what we say in public and in private, or indeed are really thinking, may lack congruency. Perhaps you have experienced being with people from your own affinity group who take it for granted everyone in the assembled gathering agrees with their stated views and biases about other diverse groups. I am Scottish and for a few years, in the e...