![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Impact of Radical Change on You, Your Organization, and Your World

When I began my undergraduate studies in mechanical engineering at Tulane University in New Orleans, I used a slide rule for making calculations. Only other baby boomers and perhaps their parents are likely to have seen an actual slide rule, much less operated one. Today my children would view it with the same disdain that we accorded the washboard, or the butter churner, or the horse and carriage—an almost charming, antiquated technology. The controversy raging at the time was the utility of the newer plastic, resin-based slide rules, which most of the students used, relative to the older model with a wooden body, favored by most of the professors. This was the kind of incremental improvement that characterized our sense of technological change in the mid-1970s. Much discussion ensued in and out of the classroom about the relative durability of the two bodies and the notches on the rule, about the coefficient of thermal expansion of plastic versus wood and the implications for accuracy of the scale at different temperatures.

And it does all seem quaint in retrospect. In the second semester of my freshman year, the first handheld electronic calculators appeared on the market. I bought a five-function calculator—it added, subtracted, multiplied, divided, and determined percentages—for $150, a small fortune for a college student. And before the end of the school term, Hewlett-Packard had introduced a next-generation programmable handheld calculator.

Science and math mid-term and final exams were typically four hours long, much of that time spent operating the slide rule and estimating the solution to a given problem. (For those of you who have never used a slide rule, the best it could deliver for all that effort was an approximate value or solution to a calculation.) By comparison, punching the numbers into a calculator and performing the appropriate mathematical operation could produce an exact solution to an equation in seconds. I finished the exams early and left while my Stone-Age peers continued to fiddle with the best equipment slide rule manufacturers could offer.

It was my first experience with the digital divide and the thrill of having so much computational power at my fingertips. A slide rule swinging from a belt soon became a rare sight on campus. Our professors devoted the newly available classroom and testing time to take us deeper into the material, expose us to a broader range of applications, provide more hands-on lab time—in short, cram a lot more learning into a semester than was previously possible now that the most time-consuming (and least value-added) aspect of mathematical computation had been reduced to a nearly negligible effort. Today there is no doubt in my mind that the engineering education my class received as a result was far richer and more extensive than that of classes that graduated just three or four years before us. By the time I landed my first engineering job, the calculator had become a fixture in the work place.

I mention the electronic calculator here only because I am able to get my head around the transformative impact it had on my education. I adapted to the technology and dare say I mastered it. In contrast, I can’t begin to comprehend all the ways the succession of developmental leaps in telecommunications, personal computers, semiconductors, and the Internet have affected my life and work over the last couple of decades. These have been more rapid, massive, complex, interdependent, and pervasive changes than anything I’d experienced before. Others of my generation and I struggle to just stay competent in a relatively narrow domain of a new world of technological wonders that continues to expand every more rapidly. But our experience is not unique.

For those of us alive today in the developed and developing worlds, the collective effects of the human body (population and labor) and the human mind (technology and culture) have transformed our world as never before. We are experiencing transformative change so rapid and pervasive that each successive generation is growing up in a markedly different world than the prior generation did, one that is also changing at an ever more rapid rate.

Transformational Tsunamis: Acceleration and Convergence

Over the span of its history, the human race has produced a host of notable technological advancements—the discovery of fire, the development of cooking, language, the printing press—that shifted the paradigms of the time and radically altered the course of human development on biological, social, political, and economic levels. However, studies of the rates of technological change present convincing evidence of rapid acceleration during the last half-century relative to historical rates, with rates of change now approaching the exponential.1 The pattern is apparent across numerous areas: strength of materials, travel speed, computational power, communications technology, communications efficiency and content, miniaturization, and others. Technical leaps in one area have spurred changes in other areas. Such rapid technological change across many fronts propagates large-scale social as well as environmental and economic change, with a transformative effect on daily life and work.

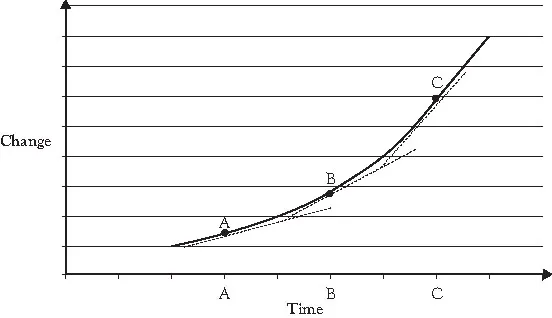

I visualize the exponential curve in Figure 1.1 as a composite of all these changes and their impacts on the lives of anyone alive at the time. The three dotted-line segments shown in the figure depict the slope of the curve, that is, the rate of change, at the corresponding point in time. As we move to the right through time, the slope of the curve steepens, indicating that the rate of change accelerates. Let’s assume for the sake of this discussion that at Point A my parents were about 30 years old, at Point B I was 30 years of age, and at Point C (in the future) my children will be about 30. As the dotted segment for Point B shows, the slope of the exponential curve is steeper at B than at A, indicating that I was experiencing a far greater rate of change at 30 than my parents had at the same stage of their life. However, my children at 30 will experience their world transforming at an even more dramatic rate than I did. This unrelenting revolutionary, not evolutionary, change will continue, thus escalating the pressure on their generation’s individual and collective abilities to integrate this change in their work and lives. Technological advancement and the social and economic tsunamis it generates would strongly suggest that the species itself must make a huge leap in how it integrates change.

Figure 1.1. Exponential change experienced by successive generations.

An Interconnected World

Humans have been coping with change and adapting for as long as we’ve walked the planet, assisted in large part by the great engine of rational thinking. As an indicator of our apparent adaptive abilities, population growth has not taken a real holiday since the plague of Black Death in the mid-fourteenth century. The number of humans on the planet, estimated to be 300 million in 1000 A.D., grew to 3 billion in 1960 and 6 billion at the beginning of this millennium, with a global population of 9 billion projected for 2040. Yet this very success contains the seeds of catastrophe.

For some 12,000 years of human history, we’d been able to produce enough food to support the population growth. However, by the end of the eighteenth century, as Thomas Robert Malthus noted in his Essay on the Principle of Population, the population growth had outstripped that of growth in agricultural production, an imbalance that set the stage in 1943 for worldwide food shortages—a Malthusian correction. The green revolution in agricultural technology and practices during the second half of the twentieth century greatly accelerated food production, and we were able to support a doubling of the world’s population. However, in the new millennium population growth has once again outstripped our ability to produce enough food. In 2007 global carryover food stocks dropped to just 61 days of global consumption, the second lowest ever recorded.2 Perhaps another paradigm shift in agricultural technology is just around the corner. Yet this is hardly the only challenge associated with the current and projected number of humans on the planet consuming resources and generating waste.

In fact, technology advancements, population growth, and their combined social, economic, and environmental impacts have created towering challenges that confront us as a species because we are interconnected to one another and everything else on the planet in ways we’ve only just begun to understand, and in new ways few would have imagined just a couple generations ago. Actions or events in one country, or in one industry, or even one company can ripple out to converge with other events or actions to generate a tsunami of change that ultimately impacts millions of beings. Even seemingly small individual actions, such as consumer decisions, when taken by millions of people have compounded effects over time and across space, with unanticipated consequences. Local action does create global change.

For example, you might drive a car that consumes gasoline and, among other factors, contributes to a huge demand for petroleum, giving the industry that produces it enormous influence in the corridors of government. Over a number of years, a U.S. federal regulatory agency that oversees the industry develops a complacent culture that influences employee attitudes and behavior. Despite a period of record-high profitability, a British petroleum company and its business partners drilling in the Gulf of Mexico make a series of questionable decisions to save time and costs. Then, over the course of a few days, the confluence of greed, less-than-perfect technology, lax oversight, and natural forces culminate in a disaster like none other the country or the earth has experienced. And it will take years to tally the toll on the environment, the economy, and individual lives and livelihoods in the region.

Finger pointing, name calling, intransigent political positions, or inflammatory rhetoric cannot eliminate the fact that, ultimately, our individual choices, as trivial or unconscious as they might seem, help to create a reality in which such disasters can—and do—occur. This raises the specter of other potential mind-blowing changes on a planetary scale.

In his book, Hot, Flat and Crowded, Thomas Friedman writes:

We can no longer expect to enjoy peace and security, economic growth, and human rights if we continue to ignore the key problems of the Energy-Climate Era: energy supply and demand, petrodictatorship, climate change, energy poverty, and biodiversity loss.3

If we pay attention, we can learn how each one of us contributes to fouling the air and the water, depleting what we’ve been accustomed to view as limitless resources, just by the simple acts of daily living we in the developed world take for granted—driving a car, consuming food from far-off places, heating and cooling our homes, throwing out what we no longer use or want.

If you had been a factory manager in Michigan, rather than a fisherman on the Gulf Coast, you’d have already learned a lot about disruptive change caused by forces seemingly beyond your control. Automotive technology advanced and consumer tastes changed—in part because growing concern about fossil fuel and all its costs motivated many people to buy smaller cars. One day your factory closes, your suppliers go bankrupt, and jobs evaporate across an entire region. The implications get very personal, very fast if it is your business or your job that disappears, your home that goes into foreclosure, your retirement fund that evaporates (although you’re still not sure whom to blame for that). Life as you once knew it is over.

If you live in Los Angeles and down-sized from a Pontiac to a Toyota hybrid, you drive a car with a smaller carbon footprint, doing what you can to curtail global warming and dependence on fossil fuels. But did you also take into account other wide-ranging consequences of your decision when combined with similar choices by many other auto buyers like yourself—such as a massive dislocation of U.S. auto industry jobs? Former autoworkers, forced by declines in personal income, shifted their shopping from Penney’s to Wal-Mart, which now imports an enormous volume of cheaper goods from China rather than from U.S. manufacturers. As it turns out, what is good for Wal-Mart and its customers has been bad for millions of other U.S. workers and their families who have seen manufacturing jobs in their industries disappear overseas. Yet this has been good for the millions in China who can now aspire to a standard of living that begins to approximate ours.

What a complex web of interdependency. Our purchasing and lifestyle decisions (not all of which are voluntary) have ramifications that we might never imagine nor intend because there are so many more of us and we are now connected in ways unique in human history. This is the convergence of tsunamis of technological, economic, environmental, and social change. We are the villains as well as the victims in this larger drama, should we choose to view it from this mindset. The boundary between my best interests and yours is rapidly dissolving.

The patterns and passages we’ve been conditioned to think of as the “normal” cycle of life and family likewise have been altered by social and economic tsunamis. New twists and complexities add unprecedented pressure to our closest relationships, personal finances, and even our very notion of family. You and your siblings, for example, might be struggling to find affordable assisted living arrangements for your elderly parents, who, thanks to developments in medical science, are living longer but not necessarily more robustly. In the wake of the public sector cutbacks for elementary education tied to massive revenue shortfalls during the worldwide economic recession, perhaps your youngest child—a recent college graduate who cannot find a teaching job despite the enormous investment you made in her education—has moved back home. Or the marriage of your eldest child has dissolved under financial and job pressures, and your grandkids will be shuttled between both their parents for who knows how long. This wasn’t your parents’ vision of their golden years, or your daughter’s vision of launching her career of service, or your vision of a stable home environment for your grandchildren. Evolution has not conditioned us as individuals or as a society to deal with the present, this present, simply because changes of this nature, frequency, and complexity have never occurred before.

The Implications in the Workplace

John Kotter, in his book, A Sense of Urgency, speaks to the impact of exponential change on business:

With episodic change, there is one big issue, such as making and integrating the largest acquisition in a firm’s history. With continuous change, some combination of acquisitions, new strategies, big IT projects, reorganizations, and the like comes at you in an almost ceaseless flow.… These two different kinds of change will continue to challenge us, but in a world where the rate of change appears to be going up and up, we are experiencing a more global shift from episodic to continuous [change], with huge implications for the issues of urgency and performance.4

A transformative change—in technology, markets, or economies—shifts or alters the value exchange between the product or service provider and its customers, revolutionizing what the customer needs, is willing to pay, and expects in return. In short, it changes the rules of the game. This applies equally to the public and the private sector. A major social, political, or economic shift can significantly alter the type, level, and/or cost of services a public agency must provide its constituents. Private sector businesses can face a burning platform that requires they find a way to provide higher value-added services or discover new market niches. Inherent in such tsunamis of change are creative opportunities to develop and deliver a new service or product that better meets customers’ new needs and expectations. For individuals and organizations with no vision for how to capitalize on the new reality, or with no capability to transform themselves and what they do, radical change can be a destructive force. Sooner or later they lose their effectiveness and ultimately their ability to secure the resources they need to operate.

John Naisbitt writes in his book, Mindset!:

The future is a collection of possibilities, directions, events, twists and turns, advances, and surprises. As time passes, everything finds its place and together all pieces form a new picture of the world. In a projection of the future, we have to anticipate where the pieces will go, and the better we understand the connections, the more accurate the picture will be.5

When I was growing up, I used to change the oil in our family car, a ′54 Chevy with enough room under the hood and around the engine to get at everything necessary to perform routine maintenance. Over what now seems a relatively short period of time, technology advances and the quest for greater fuel efficiency drove Japanese and European auto makers to build more and more horsepower into smaller and smaller engines mounted on a more compact chassis, a transformative trend that U.S. carmakers came to rather belatedly. People like me, who weren’t mechanics and didn’t have access to special equipment, found it increasingly difficult to change the oil in these compact engines, or even to slide underneath these smaller cars and find the oil filter. Spotting an opportunity, some visionary entrepreneurs conceived of a specialized facility that offered car owners the convenience of driving into a location and having someone else quickly change the oil and other fluids on the spot at a very reasonable cost. Enterprises such as Oilcan Henry sprouted up, giving birth to the drive-in oil-change business. Demand grew rapidly as car owners found more value-added things to do with their time. The concept expanded to include other related services that the auto owner or the mechanic at the local service station used to perform. Franchisers like Jiffy Lube and major retailers like Sears and Wal-Mart—who know a good opportunity when they see it—now dominate the drive-in auto service industry. Other franchisers have peeled off specialized repair services for transmissions and brakes, “filling” stations are now largely the domain of the petroleum companies and convenience stores, and the traditional neighborhood service station has all but disappeared. Survival in this new landscape was not a matter of more advertising or shaving costs but rather the ability to envision an attractive new value proposition with an existing or new customer base.

The experience of work itself is undergoing transformation. Consider the example of business travel. The advent of online booking for airlines, hotels, and rental cars transformed travel planning, allowing the frequent business traveler to dir...