SECTION 1

The Basics of Culture

CHAPTER 1

What Is Culture, Where Does It Come From?

Culture is the core determinant of all we are. It is the filter of our senses and therefore the chief controlling agent of life’s values, its perceptions, and decisions. Inspection to determine how and why people act the way they do is a far ranging field of learning. Housed in the arena of sociology and psychology the scientific discipline of anthropology studies humans across two interlinked scopes of inquiry—history and geography. The field is divided into four distinct but related subfields that impact, borrow, and therefore influence each other. They are:

1. archaeology: studying ancient and prehistoric societies;

2. physical anthropology: examining the biological make-up of human beings;

3. anthropological linguistics: a comparative inquiry into languages and communication;

4. cultural anthropology: the search for similarities and differences among contemporary peoples of the world.

Cultural anthropology looks to identify and describe how people’s thought processes produce a set of values upon which they construct their life, the choices they make, and the actions undertaken driven by varied mind-sets. While the world shares many similarities, it differs in many others. There is a marked tendency to assume that we are all alike, for example, in terms of basic human nature. This comes from the fact that most of us draw such conclusions from our limited observations of the immediate society around us. When confronted with an alien or foreign society whose people act differently from us, we think of them as weird, strange, or exhibiting downright wrong behavior. Culture is not positive or negative, it just exists. It is our judgments of culture that contain such judicial dispositions.

Our assumptions of reality are culturally bound because we practice cultural monotheism. This natural tendency disqualifies all of us to act as empathetic arbitrators of differences as we are all strongly anchored in and held back by the chains of our own culture. To unlock this judgmental stranglehold one needs to embrace the idea that cultural pluralism, in masked form, resides in all of us. We possess, although hidden from our consciousness, dormant cultural traits that mirror to an extent those people who on the surface are perceived as different from us, and vice versa—what is called the duality factor.

Exploring the Meaning of Culture

When one thinks of culture, a mirage of defining terms and examples appears. To be “cultured” is to have received an introduction to the classy things in life. We often think one who is cultured possesses a superior education or at least an awareness of such things as the fine arts and classical literature, is knowledgeable about the philosophies of great teachers, and appreciative of the music of the great masters.

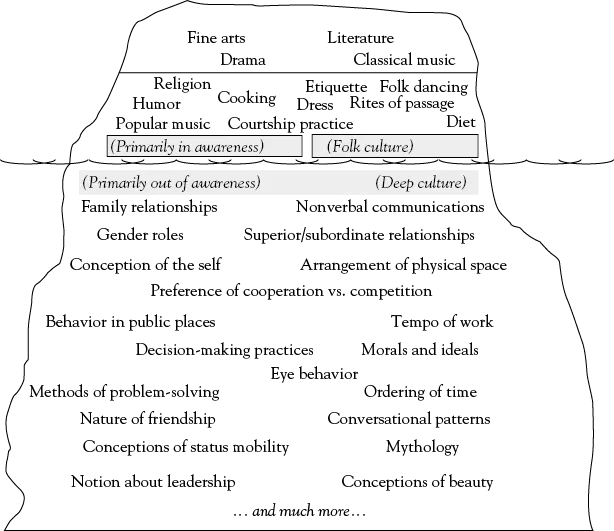

When describing the culture of a society, we normally address surface attributes—those characteristics that we can physically sense as stimulating our eyes, ears, smell, and touch. But below the illustrated surface or folk culture lies a host of hidden or deep cultural attributes. They are recessed in the mind-sets of people, exercising control over their thoughts and behavior and are responsible for their core beliefs and values—how people rationalize and think. Figure 1.1 illustrates the multisurface aspects of the cultural minutiae. Like an iceberg, most of a group’s perceived cultural attitudes, the overt, lie on the top layer while those below the surface, the covert, are revealed only when people are engaged in relationships with others and the curtain of familiarity is drawn.

Figure 1.1. The cultural iceberg.

Even our own cultural knowledge of ourselves is often masked as rarely does one take the time to examine, much less classify one’s personal tendencies, why we behave and act in a certain way. Our deep cultural identity is only challenged when we encounter an alien society and begin to perhaps question our own values in the face of differences.

Defining Culture

There may be no single acceptable definition of what is meant by the all encompassing term culture. In his book The Cultural Dimension of International Business, Gary Ferraro notes that two early researchers in the field “A. L. Kroeber and Clyde Kluckhohn in 1952 identified more than 160 different definitions of culture.”1 In its simplest description culture is a design system for living. Edward Tylor, writing over a century ago, described culture as “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.”2 M. J. Herskovits depicted culture as mental, “the man made part of the environment” as opposed to the material or physical created by nature.3 Geert Hofstede referred to the process as the “collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one group from another.”4 Hofstede described a series of habitual thinking patterns made up of shared values, beliefs, symbols, behaviors, and assumptions that define the group. Technically, culture is an abstraction that cannot be seen or touched, an intangible mental process that Hofstede further defines as an intellectual system to help people solve problems. But it is reflected in one’s activities, so it produces material examples, physically observable tangible elements from artifacts to language—the surface or above water aspects of the cultural iceberg (see Figure 1.1). In the end, culture is most vividly expressed through the values it produces in people and is exemplified by what people do and do not do in a given society—that which is considered as acceptable behavior and that which is deemed unacceptable behavior. Prevailing or dominant actions and/or reactions to life are regarded as conventional and tend to be classified to describe the culture of a given group.

It is important to remember this point when examining all these approaches to the subject of culture, as the word “collective” refers to the fact that it is contingent on the combined reflections of the members of a specific group. Hence culture is shared by two or more individuals and is indicative of their repetitive, normative, demonstrative, and therefore expected patterns of behavior—allowing one to qualify these as a deductive generalized characterization of a society. However, this consideration is both positive and negative. If we can classify a specific culture via a set of applied research-based determinants, those of oneself and others, we may learn in advance how to form relationships with them, by concentrating on the similarities but keeping in mind the differences. On the other hand, such a classification approach induces prejudices, a prejudgment that may not allow for a cultural free space to exist where one first observes before forming opinions to guide their action and reaction. Edward T. Hall warns those studying culture that it often hides more that it reveals and what it obscures most effectively is an appreciation and understanding of one’s own culture.5 Culture can therefore be a minefield of contradictions, misplaced assumptions, false observations, and tainted conclusions but its value as a relationship building tool should not be dismissed or understated. One is instructed to just tread lightly in the illuminated path it provides. The numerous sets of cross-cultural determinants, as reviewed in chapter 3, can result in a labyrinth whose positive metaphorical intent is meant to hone one’s focus and provide a pathway of understanding. But to many the vast collections turn into a maze, perverting the ability to comprehend, often confusing and trapping the cross-cultural traveler.

Where Does Culture Come From?

In the end, culture can be summarized as “everything that people have, think and do as members of their society”6; a total way of life. With representative examples of culture both above and below the surface of inspection and with defined parameters of what it is, it is valuable in understanding how it works to consider where it comes from. If culture is the sum total of one’s observations and indoctrinations it follows that it is a learned experience that begins at birth. While the hardware of our brain is biologically constructed the loaded software is placed in the mental system by interaction via our sensory mechanisms with one’s environment—the material world and relationships with its inhabitants. Unlike the genetic construction of the physical brain which is internal, cultural learning is external. This simple axiom is universal and while cultures differ around the world the process of acquiring culture is similarly reproduced in all societies.

Cultural indoctrination is the sum of all one is exposed to as we emerge from the womb, and hence it continues to death. During life it never stops. The process is composed of inputs beginning with the family unit and like the proverbial pebble thrown into a pond it radiates outward growing wider and wider as new segments of exposure are engaged. This mechanism of learning is socialization. It starts with family/kinship relationships conferring upon us our first introduction to our cultural heritage. It is influenced by the physical environment in which we live as we view how others who went before us have adapted to it. Our cultural identity is more formally built on the educational system one is placed in. It is molded on the ethical and moral teachings encountered in a society that morph into secular laws as well as spiritual guidance based on religious doctrines and philosophical approaches defining expected behavior. It is also prejudiced by unwritten customs and traditions that are followed. Hence one often hears the refrain “this just isn’t done” or “this is how we do it” without pointing to a specific educational indoctrination or authoritative prescribed written code of conduct. While one’s cultural programming includes formal and informal training it is absorbed from mere observation via general immersion in society as well as through trial and error as one is punished for unacceptable actions. It emerges from problem solving of everyday matters.

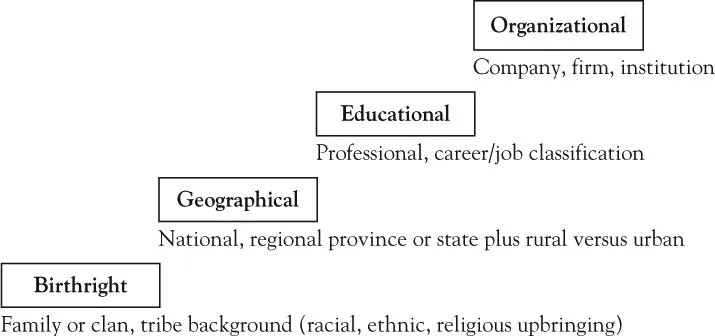

Cultural Steps: Levels of Associations Contributing to Cultural Self-Identity Building

Cultural indoctrination is a journey of steps or building levels that one goes through in a given society (see Figure 1.2). The first step is birthright cultural indoctrination initially acquired via the family one emerges from the womb or is adopted into. It is this first primary group that provides the initial level of cultural indoctrination and includes the collateral influence of a clan or tribe of common ethnic, racial, or religious/philosophical principles that the family resides in. This initial creation step in the development of one’s cultural identity is itself based on a closed groups system of mating, marriage or its monogamous equivalent, child rearing, and family structure. Even within a uniform politically designated society such family orientations produce regional differences. All our basic assumptions are tethered like a life sustaining umbilical cord to this first level and this exposure tends to act as the anchor of our core values. The saying “it takes a village to bring up a child” is indicative of the surrounding geographical social arena, one’s associations with others, that one grows in. It is also made up of one’s climatic and physical environment as well as the socioeconomic and political exposure one encounters with a particular sovereign territory. As with family units even the norms and behaviors experienced with a given bordered nation may be further segregated by differences in domestic regional characteristics setting them apart from other citizens of the same nation.

Figure 1.2. Cultural building staircase: levels of group induced affiliations.

While the nomenclature of culture is normally prescribed to identify the national culture of a particular geographical area of the world there are other influencing factors often denoted as subcultures as they are embedded in a country or regional territory. Two identifiable contributory components are educational/professional and organizational. Some would argue that these additional cultural steps are not a set of values but instead are merely a series of acceptable group practices imposed by the power channels of such institutional subgroups one associates with and hence are not a natural process of cultural assimilation.7 However, as powerful stimulators of behavior and perceptual development they are part of the cultural building process. One’s cultural path in life is further influenced by the structured choice of the formal education afforded them. From primary or grade school up and through undergraduate university, masters, and perhaps even the doctorate level such scholastic exposures to specific instructional programs and curriculums chosen alter one’s thinking matrix and cultural indoctrination. With some degrees culminating in acceptance into the professional ranks or a specialized field of study the endowments provided by one’s academic experiences assist in the manifestation of selected cultural inputs.

At the top level is organizational culture. Organizational culture is a relatively new field in the arena of cultural anthropology with research in the area pioneered by studies of commercial institutions and managerial approaches to the internal psychology, attitudes, experiences, beliefs, and values of shared groups of people operating toward a unified goal. It is the goal orientation that defines and separates this category of culture, how things are accomplished, from the normative other levels of cultural development. Organizational culture can be simply stated as the way things get done around here.8 It is reflective of a patterned activity of shared assumptions the group have evolved to solve problems. As such the paradigm created runs the gamut from mission values, the expectation or goal creator, to tangible control systems and structures while also containing influential emotion-based intangible e...