![]()

CHAPTER 1

Leadership Implosion: Failure to Change = Failure to Thrive

Jonathan Schwartz was promoted internally to chief executive officer (CEO) of Sun Microsystems in 2006 after serving in a number of vice presidential roles. Under Schwartz’s direction, the company hemorrhaged its value and was eventually sold to Oracle in 2010 and subsequently dismantled. Similarly, Marissa Mayer was brought on as CEO of Yahoo in 2012 after a successful tenure at Google, where she served as the company’s first female engineer and moved on to several senior roles. Mayer was brought in from outside the company and failed to make a successful transition to CEO at Yahoo, never implementing a cohesive strategy. She has been criticized for relying on business practices that had served her well at her former position but turned out to be ineffective at Yahoo. In both of these cases, there are indications that the failing executives demonstrated an extreme lack of understanding and appreciation for the scope and scale of their new positions.

When executives fail to meet the expectations of their roles, it is typically not a matter of intelligence, drive, energy, persistence, or intent. According to the Corporate Executive Board, 50 to 70 percent of executives fail within the first 18 months of promotion into an executive role. About 3 percent “fail spectacularly” while about 50 percent “quietly struggle.”1 This failure rate might be better understood in the case of an outside hire who is unfamiliar with the business and lacks knowledge of the culture. However, this failure rate remains true whether or not the new leader has been promoted from within or from outside the company! It is more perplexing how an internal promotion of someone would fail since they are familiar with the people, products, and customers. The fact that so many internal and external executives fail not only hurts a company, but also has long-term implications for succession planning and business continuity. In our mapping of the DNA of leadership, we have identified several common causes for these types of leadership failures.

Moving Up: Rocky Ride or Smooth Transition

In corporate America, the prevailing notion is that if you work hard and do quality work, success and recognition will follow. Very little attention is given to the perils of advancement. In fact, the higher up one moves in any organization, the more important it is to do things fundamentally differently and to adopt a significantly different leadership paradigm. This change requires moving well out of your comfort zone and trusting that, by adopting new behaviors, you can continue to be successful at this new level. Individuals frequently move up in organizations because of their ability to get tactical work completed. They become successful at the deep and narrow tasks without having developed a broader, longer-term view of the business. They assume that they will be successful in their new role by doing more of the same. In our experience, one of the great leadership failures is the inability of leaders to move into more strategic-thinking roles and out of their previously primarily tactical roles.

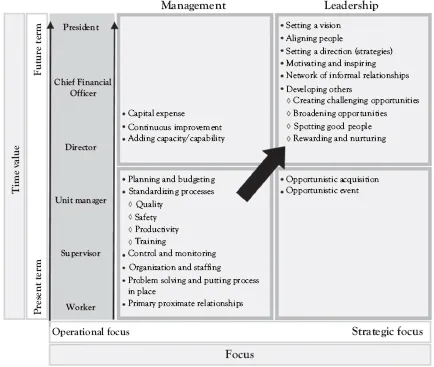

John Kotter, Harvard Business School professor, has noted that management is about coping with complexity, whereas leadership is about dealing with change. Becoming adept at short-term tactical execution is necessary for moving into higher levels in an organization. However, staying in a tactical mode will not ultimately advance a career. There are two dimensions of focus in leadership—the tactical/operational and the strategic dimensions. These dimensions are typically, though not always, linked to time. Tactical activities are usually more of short term in nature while strategic activities are usually of longer term.

Figure 1.1 demonstrates these differences and provides the pathway for moving from operational tacticians to strategic leaders. In the lower left quadrant, you will note the short-term, present-time, tactical, and operational issues. These tasks and initiatives must be executed just to keep the doors of a business open. This is the “engine” of a business. If the operations of a business are not functioning well, strategy is useless. However, well-functioning operations without strategy are a recipe for stagnation and eventual decline. The leader must ensure continuity of efficient operations while, also, looking out for the future of the organization.

Figure 1.1 Migrating to Leadership

The upper right quadrant represents the longer-term, strategic focus a leader must embrace and drive in order to help the business sustain success in the future. Note how different the foci of the two quadrants are. Strategic issues are all about longer-term succession planning; new markets; what customers will want in the future; possible acquisition targets; industry, governmental, and regulatory relationships; and setting a vision for the organization. Early in his tenure at GE, Jack Welch focused on drastically cutting costs to salvage the business. He eliminated 135,000 jobs in streamlining the business. He knew that the engine of the business was broken and needed repair. He was not afraid to “dip down” into the operations of the business to fix it. However, over time, he had the wisdom to recognize that, strategically, it is people who are at the heart of continuing to grow a business. Under his direction, he transformed the GE Management Development Institute, referred to as Crotonville, to build a new breed of leaders for GE. Ultimately, Crotonville offered over 1,800 courses to GE management throughout the world. Welch taught monthly at Crotonville and put into practice what he preached. As a result of his focus on developing leaders, when Welch left GE, the GE Board of Directors had several excellent internal candidates to consider for his position before selecting Jeff Immelt. This is a supreme example of a leader focusing on the strategic, long-term vision of a company.

It is always better when a leader understands the culture of a business and is able to incorporate that understanding into his or her thinking. The leader must have a degree of confidence that the operations of the business are running effectively and efficiently. He or she must also have ensured that the appropriate resources are available to run the operations. It is only then that the leader can begin to change his or her attention to the organization’s strategy. This is the art of managing the intersection between the operational and the strategic. He knows when it is advantageous to get involved in operations and when it is advantageous to take a broader view. The successful executive develops a sense of both timing and degree of attention required of both.

Welch captured this managing-the-intersection challenge by saying, “You can’t grow long-term if you can’t eat short-term. Anybody can manage short. Anybody can manage long. Balancing those two things is what management is.” As hockey great Wayne Gretzky has said, “a good player skates to where the puck is. A great player skates to where the puck will be.” A great leader anticipates where the business will be and begins making adaptations and revisions to get there. This anticipation requires more time spent in study, reflection, and utilization of the broader overall perspective of leadership, instead of viewing in depth the various parts of the organization.

Reestablishing Priorities: Identifying What Matters Now

You may be asking yourself where, and how, should the leader focus his or her attention? Imagine it is your first day on your new job. You have just been promoted and have moved into your big, new corner office. It is much nicer than you have had in the past, spacious with windows and a nice view, a mahogany desk and shelving, a small conference table, a wallboard with pens and an eraser. You have done well. After you settle in, you meet with your new executive assistant to review the pressing items you need ...