![]()

1

Spinning Ariadne’s Thread: Sources and Methodologies

Anne P. Chapin

“Society is founded upon cloth.”

Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881)

Woven textiles are produced by nearly all human societies. Generally defined as cloth or fabric produced by weaving, knitting, knotting, or felting, the term also refers to the fibers used to make textiles.1 Loom-woven textiles first appear in the Levant in the Early Neolithic period during the 8th millennium BC, around the time when early farmers began to raise domesticated plants and animals, establish permanent settlements, and craft pottery. Weaving, together with its associated package of technological and social innovations, spread into Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Anatolia, and then into Greece, Europe, and central Asia.2 These early textiles were put to a wide variety of uses: new forms of clothing could be made, since fabrics can be woven in all manner of shapes, sizes, and thicknesses and are thus more easily fashioned into clothing than tanned leather hides from animals. Textiles also served ceremonial, funerary, and household purposes, and were put to agricultural, industrial, and commercial use. Advances in seafaring and military technologies have also been linked to the development of textiles.3

This volume investigates evidence for patterned textiles (that is, textiles woven with elaborate designs) that were produced by two early Mediterranean civilizations: the Minoans of Crete and the Mycenaeans of mainland Greece (Fig. 1.1).4 These two cultures prospered during the Aegean Bronze Age, c. 3000–1200 BC, contemporary with pharaonic Egypt (Fig. 1.2), and both could boast of specialists in textile production. Their cultures also developed lavish palaces, extensive cities, and prosperous towns run by extensive governmental bureaucracies whose economic transactions were recorded on clay tablets. These texts are written in the early scripts identified today as Linear A and B and demonstrate that the Mycenaeans spoke an early form of Greek (while the language of the Minoans remains unknown). The archaeological and documentary evidence thus indicates that even though formal written histories do not survive, these cultures were sophisticated in their literacy, their technologies, and their long-distance trade networks, which brought them into contact with Egypt and other civilizations of the Mediterranean.5

Archaeological evidence further suggests that Minoan and Mycenaean textiles were much desired as trade goods. Artistic images of their fabrics preserved both in the Aegean and in other parts of the Mediterranean seem to justify this desire, for they show elaborate patterns woven with rich decorative detail and color. Unfortunately, only a few small scraps of textiles survive today (see Chapter 2), but evidence for their production is abundant, from flax seeds and woolly sheep bones to spindle whorls and loom weights, from crushed murex shells and dying vats to references to textiles on Linear A and B tablets. And, most important for this study, frescoes painted by Minoan and Mycenaean artists supply detailed information about a wide variety of now-lost textile goods. From the luxurious costumes of women and men to beautifully patterned wall hangings and carpets, to the more utilitarian pieces of decorated fabric used for the ikria (stern screens), deck furnishings, and sails of ships, images of textiles abound in Aegean art. These elaborate textiles (and the artwork that depicts them) are the subject of this volume. A review of surviving artistic and archaeological evidence indicates that textiles played essential practical and social roles in both Minoan and Mycenaean societies. The goal of this study is to show that Thomas Carlyle’s well-known observation that “society is founded upon cloth” is as true of the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures of the Aegean as it is for modern society today.

Fig. 1.1. Map of the Aegean (A. Chapin and J. Silva)

Fig. 1.2. Chronological chart of the Aegean Bronze Age

Textiles in Greek mythology

Scattered among the rich stories that comprise the mythology of Classical antiquity are tales of spinners and weavers.6 The Moirai, the three goddesses of fate, spin the thread of life, measure the thread, and finally cut it; and thus Classical Greek ideas about human mortality were expressed in textile terms. From Crete comes Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos of Knossos, who fatefully gave Theseus a ball of thread so the young Greek hero would not get lost in the labyrinth on his quest to slay the monstrous Minotaur.7 From Greece is Penelope, faithful and resourceful wife of Odysseus and queen of Ithaca, who kept her many suitors at bay by promising to remarry only when she had finished a cloth which she wove by day and unraveled each night. Circe and Calypso, enchantresses encountered by Odysseus on his long journey home, were weavers, as are all women in the Homeric poems.8 The most famous weaver of mythic tradition, perhaps, is Arachne, a girl from Lydia who learned weaving from Athena herself and foolishly challenged the goddess to a weaving contest, only to be turned into a spider so that she would weave forever.9 Stories such as these hint at the importance of spinning and weaving in prehistory, but as Classical myths, their meanings are metaphorical rather than factual or historical. Direct evidence for the importance of woven textiles to early societies must be sought in the archaeological material.

Fine textiles and Aegean society

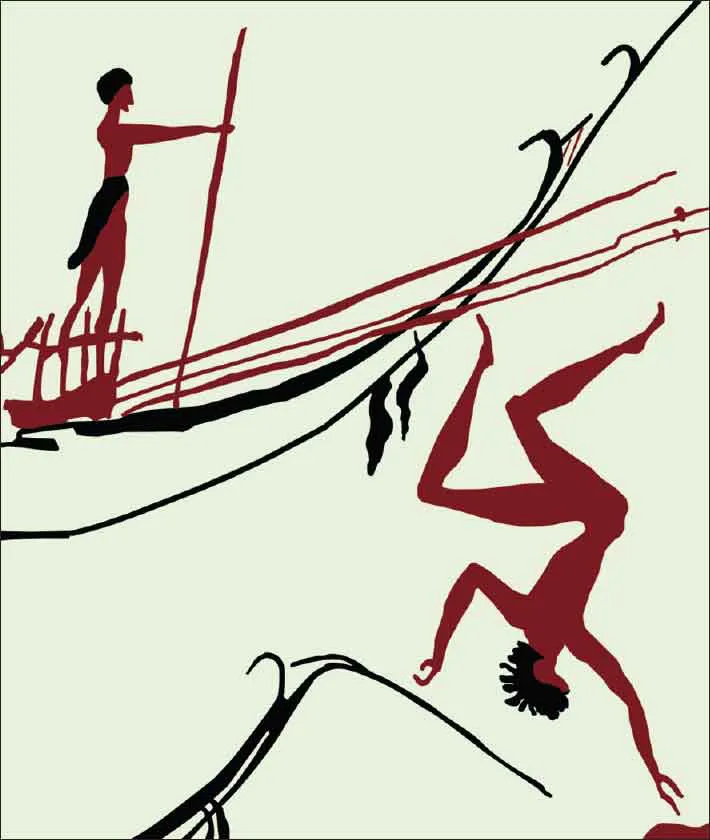

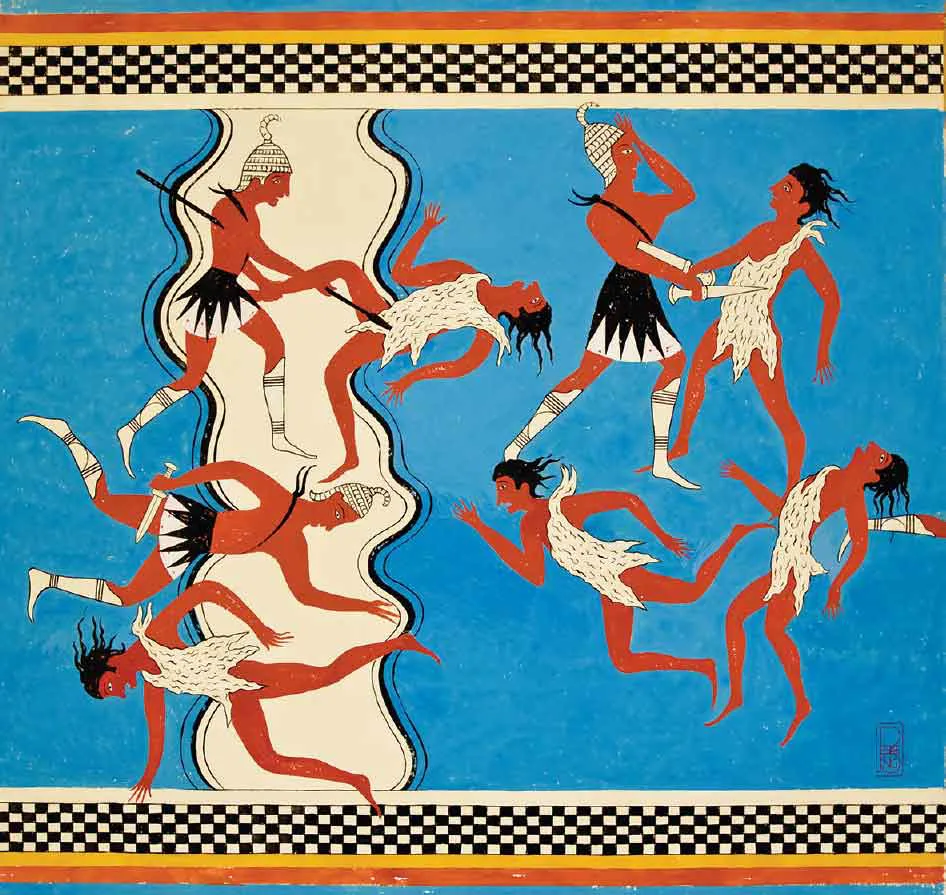

A starting point for investigating prehistoric Aegean interest in fine cloth may be found, perhaps unexpectedly, in two battle frescoes. The first, dating to the Neopalatial era, is the Shipwreck scene of Room 5 in the West House at Akrotiri, Thera.10 This small but interesting vignette depicts a naval officer extending a staff in a gesture of power over naked enemies as they drift, lifeless and drowned in the sea (Fig. 1.3). The staff bearer’s body language would seem to suggest that nakedness in battle was associated with cultural and military defeat.11 The second fresco, Mycenaean in date, decorated a ceremonial hall in the palace at Pylos during the 13th century BC (Fig. 1.4).12 This scene depicts Mycenaean Greeks, identifiable from their kilts, greaves, and boars’ tusk helmets (which are characteristic of Aegean armor) fighting an enemy that is helmetless and wears only rough animal skins. Since they are clearly not Mycenaean, the identity of the skin-clad fighters remains something of a puzzle. Details of their costuming offer the most significant clues, particularly the animal skins whose white color and hairy markings identify them as sheep hides worn by tying two legs around a shoulder. In contrast to the neat cloth kilts and stitched black leather(?) lappets of the Mycenaeans, these costumes are rudimentary and could be made without fabric or sewing. The absence of textiles, then, categorizes the skin-clad warriors as un-Mycenaean – and what is more, as rough and uncivilized.13 The Mycenaean Greeks themselves, then, seem to have associated cloth with civilization, and used the lack of cloth to represent a simple and backwards culture.

Though textiles distinguished Mycenaeans from their culturally “barbaric” opponents, textile production was actually widespread throughout Europe, the Near East, Egypt, and central Asia during the Bronze Age, and a great variety of textiles were being produced. This is evident in Egyptian art, where cloth and dress distinguish various ethnic groups (e.g., Asiatics and Libyans) from Egyptians.14 Given the language and cultural differences between Minoans and Mycenaeans, one might hypothesize that Aegean artists would likewise differentiate among the various ethnic groups populating Crete, mainland Greece, and the islands, but recent investigation indicates that this was not the case. Instead, the peoples of the Aegean embraced pan-Aegean costuming traditions regardless of language or ethnicity.15

Fig. 1.3. Shipwreck scene, from the north wall of Room 5, West House, Akrotiri (drawing A. Chapin and J. Silvia after Doumas 1992, pl. 29)

Fig. 1.4. Battle Fresco (22 H 64) from Pylos (restoration P. de Jong; courtesy of the Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati)

This broad cultural uniformity did not, however, extend to social status. Variations in cloth quality and pattern in the costumes depicted in the miniature frescoes of the Neopalatial Minoan period, which depict dozens, or even hundreds, of people in a single composition, preserve images of complex social interactions and hierarchies. The best-preserved miniature frescoes come from Room 5 in the West House of Akrotiri on Thera; the Shipwreck scene pictured in Figure 1.3 belongs to this pictorial program. The frescoes are dated to the Late Cycladic (LC) I period before the eruption of the Santorini volcano (c. 1630 BC in the high chronology), when the Minoan palaces on Crete were thriving. The paintings decorated the room’s four walls just below ceiling level: the Flotilla Fresco from the south wall shows a naval procession leaving a Departure Town and heading to an Arrival Town.16 Details of geology and setting suggest that the ships may be crossing the island’s caldera from one promontory to another, and some scholars believe that the Arrival Town depicts Akrotiri itself, with the most decorated ship being captained by the owner of the West House.17

What is interesting for this inquiry is that of the hundreds of figures and the wide variety of costumes detailed in the West House frescoes, none wears clothing made of the elaborately patterned textiles investigated here (especially Chapter 3). Rather, the fabrics are unadorned and the costumes seem humble. The more prominent women in the Arrival Town wear simple striped clothing; distinguished men seated on ships wear plain cloth cloaks, some with black borders; working men wear loin cloths while still others are nude; and some townspeople of both sexes (peasants?) are dressed in hairy garments sewn from animal skins (Fig. 1.5). In contrast to these ordinary people, the adjacent “Priestess” Fresco, which is painted on a much larger scale, depicts a young woman wearing a fringed mantle over a delicately patterned short-sleeved garment typical of Neopalatial Minoan elite costume (Fig. 1.5). The interlocking circles create a complicated fabric design with a rich texture that stands in sharp contrast to the plain weaves of the townspeople and pea...