![]()

Chapter 1

Paleolithic Animal Remains in the Mount Carmel Caves: A Review of the Historical and Modern Research

Reuven Yeshurun

This paper summarizes past and contemporary archaeofaunal research in the newly-inscribed World Heritage Site of Nahal Me‛arot (the Mount Carmel Caves) in Israel. The site, containing the caves of Tabun, Jamal, el-Wad and Skhul, exhibits a long Lower Paleolithic to Epipaleolithic sequence, important Mousterian human fossils, and the first Natufian basecamp to be explored. Fieldwork in the caves commenced in 1928 and was shortly followed by Dorothea Bate’s seminal work on the fauna, setting a baseline for the Levant’s Pleistocene faunal succession. Bate’s results and interpretations have been discussed and contested or adopted ever since. The history of archaeofaunal research from the 1930s to the present is reviewed and the results are critically evaluated in light of recent research in the Levant. The evolution of archaeofaunal research at Nahal Me‛arot neatly summarizes global developments in Paleolithic faunal studies during the last eighty years. Ultimately, a Middle Paleolithic prey-choice pattern and the Natufian economic transition emerge out of these research efforts, as well as evidence for remarkable stability and resilience of Pleistocene paleoenvironments in the Mediterranean Levant.

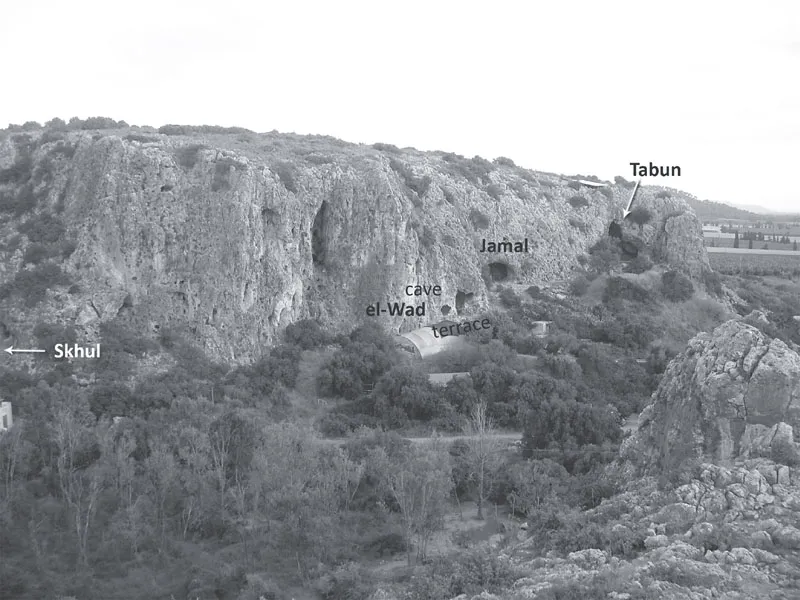

Only a few case studies provide as nearly a complete overview of the development of archaeofaunal research during the last 80 years, as does the history of animal bone studies in the Mount Carmel Caves. The prehistoric site of Nahal Me‛arot or Wadi el-Mughara (Valley of the Caves) consists of the caves of Tabun, Jamal, el-Wad, and Skhul, all clustered in a cliff overlooking the narrow Mediterranean coastal plain in northern Israel (Fig. 1.1). The caves display a long cultural sequence lasting >500,000 years, from the Lower Paleolithic to the late Epipaleolithic (Weinstein-Evron 2014). The site has been well-known ever since the excavation campaign by British archaeologist Dorothy Garrod from 1929 to 1934, which culminated in two classic publications (Garrod and Bate 1937; McCown and Keith 1939). During that campaign, important Mousterian human fossils were unearthed in the Tabun and Skhul caves, and the first Natufian basecamp to be explored was excavated at el-Wad. The long cultural sequence and important finds, serving as they have as a baseline for Near Eastern prehistory for many years, were main factors in its inscription in the World Heritage list by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 2012.

Animal bone studies were incorporated into the project from the beginning of field research. The final publication of Garrod’s excavations included Dorothea Bate’s seminal report on the faunal remains (Bate 1937), setting a baseline for the Pleistocene faunal succession of the Levant. Bate’s results and interpretations have been discussed and contested or adopted in numerous studies ever since (e.g. Bar-Oz 2004; Bar-Oz et al. 2013; Davis 1982; Dayan 1994a; Garrard 1982; Henry 1975; Higgs 1967; Saxon 1974; Speth and Tchernov 2007; Tchernov 1968; Weinstein-Evron 1994; Yeshurun 2013; Zeuner 1963). The history of the Nahal Me‛arot archaeofaunal research from the 1930s to the present is reviewed here and the results are critically evaluated in light of current research on the site and the region. Following the presentation of the various paleontological and zooarchaeological studies and their evaluation, the Nahal Me‛arot archaeofaunal research is seen as reflecting the development of zooarchaeology, from a paleontological scholarship concerned with grossly reconstructing regional paleoenvironments to a localized, taphonomic-based discipline aimed at deciphering human ecology and behavior and reconstructing social perspectives.

Fig. 1.1. The Nahal Me‛arot cliff facing south; the caves of el-Wad, Jamal, and Tabun are visible. Photograph by Reuven Kapul.

Archaeological research in the Mount Carmel Caves

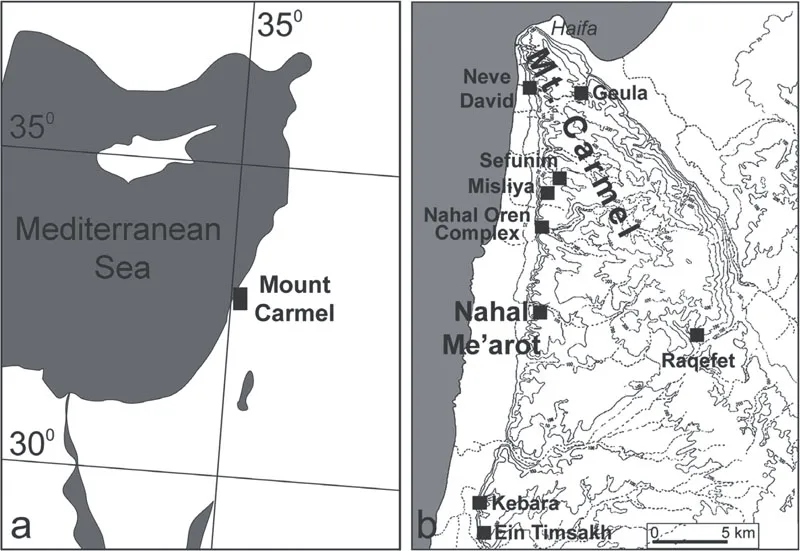

Mount Carmel is an elevated, triangular-shaped area of mostly Cenomanian rock, extending over an area of 232 km2 in northern Israel, very close to the Mediterranean coast (Fig. 1.2). The highest summit is 546 m above modern sea level (ASL), but the lower (western) parts of the mountain are only 100–200 m ASL. The proximity to the sea means that the mountain enjoys 600–800 mm of annual rainfall, producing a relatively lush vegetation cover of Mediterranean maquis (Naveh 1984). The Nahal Me‛arot caves are situated on the western face of Mount Carmel, where the cliff of the mountain meets the open expanses of the Mediterranean coastal plain, 45–60 m above modern sea level and 4 km east of the coastline, within the Mediterranean climatic zone of the Levant (Fig. 1.2).

Fig. 1.2. Location map of the Nahal Me‛arot caves (Tabun, Jamal, el-Wad, and Skhul) and other Mount Carmel sites mentioned in the text.

The first investigation took place in 1928, when Charles Lambert was sent to investigate the caves on behalf of the Palestine Department of Antiquities, in preparation for the then-planned quarrying away of the cliff. Lambert’s finds of the still as yet undefined Natufian Culture of el-Wad led to the recognition of the site’s importance (Weinstein-Evron 2009) and Dorothy Garrod was subsequently dispatched to begin a systematic investigation of the Mount Carmel Caves. Her campaign, together with Theodore McCown, was conducted over five seasons from 1929 to 1933 and was summarized shortly thereafter in the two volumes which gained much renown for the caves (Garrod and Bate 1937; McCown and Keith 1939). At el-Wad, Garrod incorporated Lambert’s trenches into her extensive excavations of nearly the entire central terrace, Chambers I and II, and much of the cave’s dark Chamber III. She discerned Middle Paleolithic (Mousterian) and Upper Paleolithic (Aurignacian and Atlitian) strata, overlain by thick Natufian deposits. The latter turned out to be a rich Natufian basecamp, the first to be explored, encompassing stone-built walls and pavements, cemeteries, art objects, and abundant cultural material. The definition and interpretation of the Natufian Culture, which essentially remains in force to the present-day, was largely based on these finds (Garrod 1957).

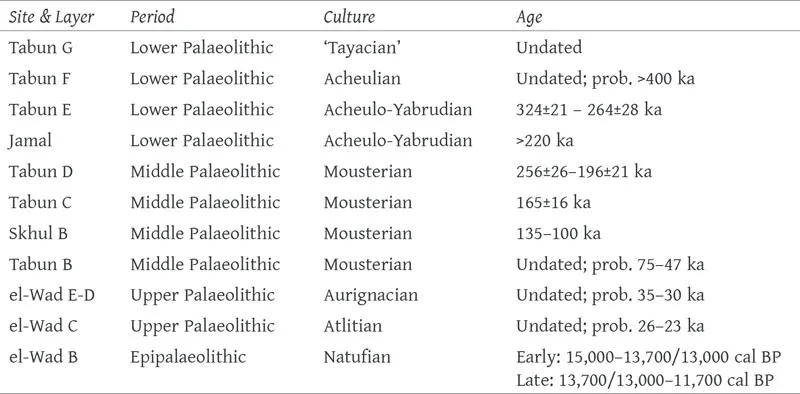

Fifty meters southwest of el-Wad, Garrod excavated the two front chambers of the Tabun Cave, which turned out to be a massive, 25 m thick accumulation of Lower Paleolithic (Upper Acheulian and what would eventually be called Acheulo-Yabrudian) and Middle Paleolithic (Mousterian) layers. The time span represented by the Tabun deposits is conservatively estimated as >500,000 years (Ronen et al. 2011). Two types of human fossils were found in Tabun’s Layer C, a mandible of debated taxonomic affinity, perhaps an early Homo sapiens (Moskovitz and Smith 2005), and a Neanderthal burial. The latter may have been an intrusion from Layer B (Bar-Yosef and Callander 1999). About 150 m northeast of Tabun, the Skhul Cave was excavated during the same years, by Theodore McCown, exposing brecciated Middle Paleolithic deposits containing human remains, currently dated to ca. 135–100 ka (Grün et al. 2005). These remains were later identified as early anatomically-modern humans, interred with lumps of ochre, marine shell beads, and a grave offering – a boar mandible placed on the chest of one individual. The Skhul and Tabun hominin fossils have figured prominently in subsequent reconstructions of human evolution and dispersal (e.g. Bar-Yosef and Vandermeersch 1993; Kaufman 2001; Klein 2009). The combined cultural span of the Tabun and el-Wad Caves offered the most complete prehistoric sequence of the Near East, from the Lower Paleolithic through the Middle Paleolithic, the Upper Paleolithic, and the Late Epipaleolithic Natufian Culture (Table 1.1).

The next campaign at the site took place during five seasons from 1967 to 1971. Arthur Jelinek excavated the upper (Middle Paleolithic) part of the Tabun profile, for the first time employing systematic recovery methods and applying new techniques in sedimentology and palynology (Jelinek 1982; Jelinek et al. 1973). Subsequently, Avraham Ronen excavated the lower (Lower Paleolithic) part of Garrod’s profile from 1975 to 2003 (Ronen et al. 2011; Ronen and Tsatskin 1995). Jamal Cave, located between Tabun and el-Wad, was excavated by Mina Weinstein-Evron from 1992 to 1994 yielding an Acheulo-Yabrudian industry (Weinstein-Evron and Tsatskin 1994; Zaidner et al. 2005). At el-Wad, the Natufian stratigraphy was refined from 1980 to 1981, when limited excavations were conducted by François Valla and Ofer Bar-Yosef on the terrace (Valla et al. 1986). From 1988 to 1989, Mina Weinstein-Evron (1998) carried out limited excavations in Chamber III of the el-Wad Cave. Weinstein-Evron, Daniel Kaufman, and the author have been excavating the Natufian deposits in the northeast terrace of el-Wad since 1994 (Weinstein-Evron et al. 2007, 2012a, 2013). Importantly, all of these projects, starting with Jelinek’s, emphasized systematic retrieval of faunal (and other) remains by sieving. However, in the renewed projects significant faunal assemblages have only been discovered in the Natufian deposits of el-Wad, with the exception of a microvertebrate collection from Jelinek’s Tabun excavation.

Table 1.1. Garrod’s cultural sequence at Nahal Me‛arot (Garrod and Bate 1937).

Note: The modern chronological framework given above is based on Mercier and Valladas (2003), Grün et al. (2005), and Weinstein-Evron et al. (2001, 2012a). For undated strata the age is based upon culturally similar deposits at other sites in the Levant (Bar-Yosef and Garfinkel 2007). Note that Tabun B has been dated by several methods which have not yielded consistent results (see Hovers 2009: 268).

Extensive fieldwork has been conducted in nearby caves in Mount Carmel. The mountain displays a rich prehistoric sequence in ca. 200 caves, rock-shelters, and open-air sites, spanning hundreds of thousands of years from the Middle Pleistocene (Olami 1984). Notable systematic excavations outside Nahal Me‛arot include the Kebara Cave (Bar-Yosef and Vandermeersch 2007), the Raqefet Cave (Nadel et al. 2012), and the Sefunim Cave (Ronen 1984), all of which have been excavated by several expeditions revealing late Middle Paleolithic to Epipaleolithic layers; the Misliya Cave, where an Acheulo-Yabrudian to Early Mousterian sequence was found (Weinstein-Evron et al. 2012b); the Middle Paleolithic cave of Geula (Wreschner 1967); the Epipaleolithic-Early Neolithic site of Nahal Oren (Stekelis and Yizraeli 1963); and the Epipaleolithic site of Neve David (Kaufman 1989).

Animal remains in the Mount Carmel Caves

The beginning: taxonomy and paleoenvironments

“The most important information which the prehistorian may hope to glean from a cave fauna seems to be whether or not it provides any evidence of differences from the animal population now living in the same area.” (Bate 1932: 277).

The first to study the Nahal Me‛arot faunas was the British paleontologist Dorothea Bate, who produced a seminal faunal report (Bate 1937). The collaboration between the excavators (Garrod and her team) and the faunal analyst was exceptional. In addition to the mutual research interests, Bate and Garrod were close friends and Bate spent some time in the field during the excavations, getting a first-hand impression of the context of the finds (Shindler 2005). In spite of this fact, Bate’s research goals had nothing to do with the archaeology of the caves; her aim, in line with the accepted practice of her time, was the reconstruction of the natural history of the Pleistocene fauna of the Levant region. Although she was fully aware of the association of the fossils with numerous human occupations (e.g. Bate 1937: 140), she did not deal with the human impact on the assemblages or attempt to raise economic and behavioral questions, with the important exception of dog domestication (see below). Nevertheless, her study of the fauna of the Carmel Caves was pioneering in many respects. She described several new species, and identified several others which had not previously been known to have existed in this country in the Pleistocene; she constructed one of the first quantitative curves of faunal succession and discussed its bearing on the ancient climate; she identified a faunal break between primitive and modern-like mammal communities during the Middle Paleolithic; and she recognized for the first time a domestic animal in the Pleistocene.

The two most abundant species in the Nahal Me‛arot sequence, showing marked fluctuations in their relative frequency through time, were the Mesopotamian fallow deer (Dama mesopotamica) and the mountain gazelle (Gazela gazella; initially defined as Gazella spp. by Bate). Bate attributed shifts from d...