eBook - ePub

An Anglo-Saxon Cemetry at Collingbourne Ducis, Wiltshire

- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Anglo-Saxon Cemetry at Collingbourne Ducis, Wiltshire

About this book

Excavations at Collingbourne Ducis revealed almost the full extent of a late 5th–7th century cemetery first recorded in 1974, providing one of the largest samples of burial remains from Anglo-Saxon Wiltshire. The cemetery lies 200 m to the north-east of a broadly contemporaneous settlement on lower lying ground next to the River Bourne.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An Anglo-Saxon Cemetry at Collingbourne Ducis, Wiltshire by Kirsten Egging Dinwiddy, Nick Stoodley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European Medieval History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Project Background

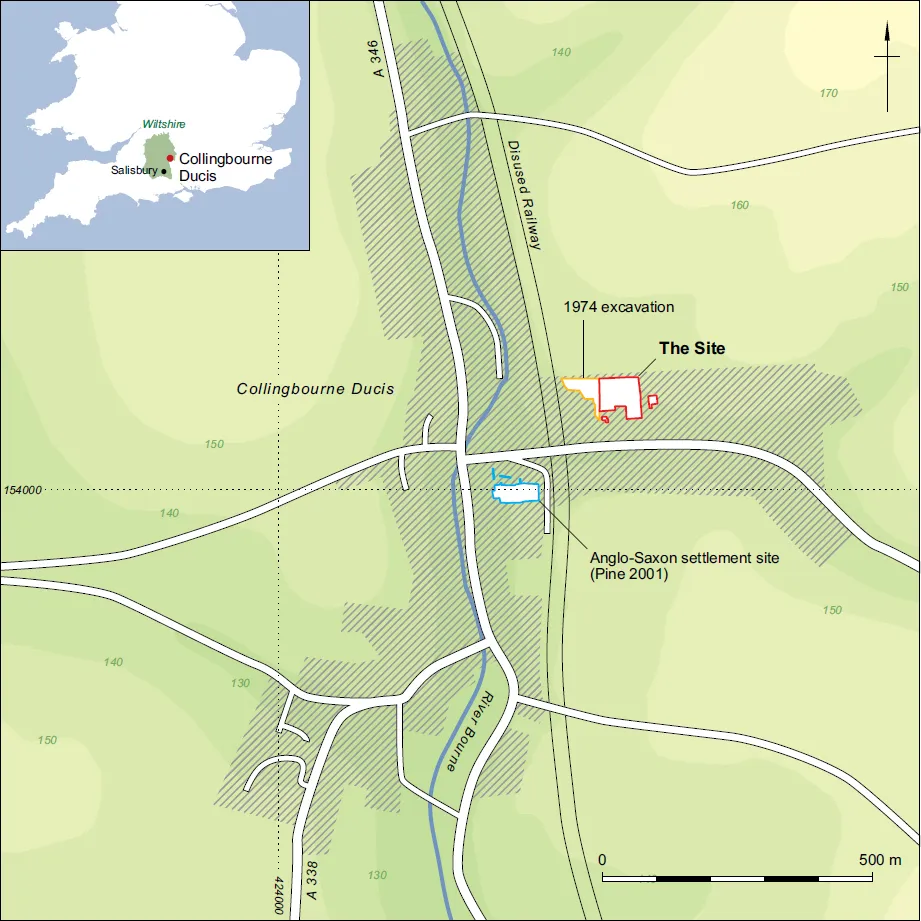

The cemetery was discovered in 1974 during groundworks for the Saxon Rise residential development (Gingell 1978; Fig. 1.1). Between 2006 and 2009, the land immediately to the east and southeast was subject to a programme of archaeological investigations ahead of housing construction and during minor works in adjacent gardens, and it is the results of these investigations which are presented here. The western limit of the cemetery was identified during the earlier excavations, whilst the most recent works confirmed its extent to the north, south and east. It is likely that the majority of the original cemetery features have been revealed and investigated.

Location, Topography and Geology

The site lay on the eastern side of the Wiltshire downland village of Collingbourne Ducis, between Marlborough and Amesbury (SU 2463 5419; Fig. 1.1). The village, situated in a valley on the eastern edge of Salisbury Plain, derives its name from the River Bourne – a tributary of the Avon – that runs 200 m to the west; the Upper Bourne river was previously known as the Coll. The Marlborough–Andover road (A338 and A346) passes north–south through the village and likely follows an early route along the Bourne Valley (Baggs et al. 1999; Kennet District Council (KDC) 2002, 1).

The site comprised two excavation areas, one of 4840 m2 investigated in 2007 and a further 80 m2 investigated in 2009. It was situated on a south-facing slope (140 m to 131 m above Ordnance Datum), mainly in an area of pasture and dense scrubland. Private gardens associated with residential developments bound the site to the south, east and west, the earliest of these having led to the initial investigation of the cemetery in 1974 (Gingell 1978). Arable farmland lay to the north.

The underlying natural deposits comprise heavily weathered, periglacially scarred Upper Cretaceous Chalk overlain by colluvial deposits up to 1 m thick towards the base of the slope and within the shallow central coombe (Fig. 1.2; Pl. 1.1). Soils are mapped as brown forest and grey-brown podsolic, and brown forest with redzinas (Geological Survey of Great Britain, sheet 283).

Plate 1.1 Central southern area of the site, with coombe to the right (from the north-west)

Figure 1.1 Site location plan

Archaeological and Historical Background

Collingbourne Ducis is located in a rich archaeological landscape that contains Salisbury Plain and the Stonehenge World Heritage Site to the west. The extensive and abundant archaeological remains demonstrate settlement and mortuary activity from the later prehistoric period onwards (Richards 1991; Fitzpatrick and Morris 1994; Cleal et al. 1995, Lawson 2000; McOmish et al. 2002; Brown et al. 2006; Fulford et al. 2006).

On Fairmile Down, only a few kilometres to the north-east of Collingbourne Ducis, is a wellpreserved Neolithic long barrow – Scheduled Monument List Entry Number (SM No.) 1013051 – one of several such monuments recorded in the wider area. Sidbury Hill (SM No. 1010138), 4.5 km to the south-west at North Tidworth, is known to have been occupied during the Neolithic period (KDC 2002, 54; Castleden 1992, 212).

There is an abundance of Bronze Age barrows in the vicinity of Collingbourne Ducis, such as those at Wick Down 2 km to the east, and Hougoumont Farm 2 km to the south-west (SM No. 1012510 and 1009925 respectively). Such monuments sometimes provided a focus for later activity, as evidenced locally by slightly later secondary burials and settlement at the extensive barrow cemetery at Snail Down, Salisbury Plain (SM No. 1009351; Thomas 2005), and the establishment of Anglo-Saxon cemeteries including those recorded on the Old Dairy site in Amesbury, and Barrow Clump (SM No. 1009697) near Figheldean; (Gingell 1978, 61; Wessex Archaeology 2013; Harding and Stoodley forthcoming). Extensive later prehistoric field systems have been identified in the village environs (Baggs et al. 1999, 2), and a number of large, later prehistoric enclosures are recorded to the west, for example at Godsbury near Burbage (SM No. 1004759), Everleigh Down (SM No. 1010066, 1009445) and Figheldean, Fittleton (Applebaum 1954). Substantial earthworks thought to be prehistoric territorial land-markers – the Wessex Linear Ditches – extend across Salisbury Plain and beyond; some form parts of the parish boundary of Collingbourne Kingston (Baggs et al. 1999, 1).

Figure 1.2 Cemetery plan: graves and other features

The substantial East Chisenbury Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age midden (Wiltshire and Swindon Historic Environment Record No. MWI13881) is situated approximately 10 km to the west, perhaps indicating periodic, significant gatherings of peoples in the region (McOmish et al 2010; Tubb 2011). Prehistoric and Romano-British field systems and landscapes are recorded nearby at Figheldean (SM No. 107939), whilst the aforementioned Sidbury Hill features the remains of a bivallate Iron Age hillfort.

There are many examples of Romano-British settlement and other activity on Salisbury Plain, particularly on the spurs of higher ground (Bonney 1979, 46–7, fig. 4.5; McOmish et al. 2002, Fulford et al. 2006). Chisenbury Warren (SM No. 1010053; McOmish et al. 2002), a Romano-British settlement connected via a trackway to Lidbury Camp, lies a few kilometres to the west of Collingbourne Ducis.

Evidence suggests that in the post-Roman period much of what is now Wiltshire came under the control of the Saxon peoples, possibly those later known as the Geurissae of the Upper Thames Valley (Williams and Newman 2006).

The ‘Conversion Period’ (c. AD 600–850) was a time of upheaval featuring changes to the political landscape and the adoption of Christianity (Geake 1997, 24, 131–4), when social organisation became more rigid and stable. Changes in dress and weaponry were marked in the 7th century, followed by changes in burial customs. A move away from furnished burial in field cemeteries to unfurnished burials in churchyards occurred variably between the late 7th to late 9th centuries, and a distinct drop in the number of furnished graves (initially amongst the elite) is evident from the early 8th century (Geake 1997).

The name ‘Collingbourne’ is thought to be of Anglo-Saxon derivation, meaning ‘stream of the dwellers on the [river] coll’, or the stream of ‘Cols/Cola’s family or followers’ (Ekwall 1991, 117; Mills 1991, 86–7). By the end of the 9th century the settlement, now known as Collingbourne Ducis, was well established. It was the subject of a Royal charter in AD 903 that distinguished it (Colengaburn Minor) from its larger neighbour ‘Colengaburn Major’ – Collingbourne Kingston. Collingbourne Ducis was part of lands given to Winchester Minster by Edward the Elder in 903, but it soon returned to the crown. Wulfgar, made an Earl by Aethelstan in 938, and dying in 948, listed Collingbourne along with several other estates in his will, with Aughton, a small village to the north-west of Collingbourne Kingston, left to and named for his wife Aeffe (KDC 2002, 1).

In 1974 the construction of a housing estate immediately to the west of the site led to the discovery of 33 late 5th- to 7th-century graves (Fig. 1.1; Gingell 1978). The assemblage comprised the remains of a minimum of 31 individuals, including four infants, three juveniles, three subadult/adults and 19 adults (nine male, eight female), consistent with a ‘normal’ domestic population. Many of the burials were inclusive of grave goods such as weapons and personal items. The published demographic data for this material has been treated with caution as there have been subsequent advances in ageing and sexing techniques. However, the overall results, including the types, date and distribution of the metalwork, have been considered below.

Subsequent investigations beginning in 2006, comprising a ground penetrating radar survey (Stratascan 2006), an evaluation (Wessex Archaeology 2006) and two watching briefs (Wessex Archaeology 2009a; 2009b) confirmed that the cemetery continued to the east and south-east of the location of the 1974 excavation, into the area forming the focus of this report.

The cemetery is one of several broadly contemporaneous examples in the region. It lay approximately midway between those at Blacknall Field, Pewsey and Portway, Andover (Annable and Eagles 2010; Cook and Dacre 1985), with Market Lavington further to the west (Williams and Newman 2006), Aldbourne, near Marlborough to the north (Stoodley et al. 2012), and Winterbourne Gunner to the south (Musty and Stratton 1964). Others nearby include Old Dairy, Amesbury and Barrow Clump, Figheldean (Wessex Archaeology 2013; Stoodley forthcoming; Harding and Stoodley forthcoming).

Settlement evidence is, by contrast, relatively rare. However, part of an Anglo-Saxon rural settlement, including several sunken-featured buildings, was discovered in the centre of Collingbourne Ducis in 1998, 200 m to the south-west of the site, and on the eastern side of the River Bourne (Pine 2001; see Fig. 1.1). Although predominantly of 8th- to 10th-century date, one radiocarbon-dated structure provided evidence for 5th- to 7th-century occupation, contemporary with the cemetery. Several disc and saucer brooches have also been found in Collingbourne Kingston suggesting that another cemetery broadly contemporary with that at Collingbourne Ducis may lay a short distance upstream, perhaps related to a further settlement (Annable and Eagles 2010, 106).

By 1086 and the compilation of Domesday, Collingbourne’s population numbered around 300–400 individuals (Wood 1986, 109), however the entry does not acknowledge the division between the two Collingbournes, with both described under the name ‘Coleburne’ (KDC 2002, 1). The village was for a brief period Collingbourne ‘Earls’, when John of Gaunt acquired the land; ‘Ducis’ was added when he was made Duke of Lancaster in the late 14th century (Ekwall 1991, 117; Mills 1991, 86–7).

In later centuries the local economy was principally agricultural and forestry-based and there is no reason to suppose the situation was any different in the Anglo-Saxon period. The downland provided reasonably fertile arable land, but was particularly suitable for pasture. Chute Forest, remnants of which still exist 2 km to the east, would have provided good opportunities for swine herding, nut harvesting and the procurement of other woodland resources (KDC 2002).

Methodology

All excavation and post-excavation procedures followed Wessex Archaeology’s guidelines, which complied with all legislation (up to early 2009) and recommended standards current at the time. A full archive has been compiled and forms the foundation of the analysis and interpretation presented here. Specialist methodologies are summarised in the relevant sections.

The archive will be deposited at the Wiltshire Heritage Museum, Devizes, under site codes 62670, 62671, 71750 and 71830.

Chapter 2

The Cemetery

The evidence presented here comprises a summary of the results of the 2007 and 2009 excavations, with reference to earlier investigations where appropriate. Grave numbers were assigned in postexcavation in order to continue the sequence from the previous excavation.

Soil Sequence

The topsoil comprised an approximately 0.24 m deep dark brown clay loam with chalk inclusions. The underlying reddish brown silty clay subsoil (0.62 m to 0.98 m deep) extended across the entire site; this colluvial deposit was deepest downslope to the south and within the coombe (Fig. 1.2), and less substantial to the nort...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Plates

- List of Tables

- List of contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Abstract

- Foreign language summaries

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: The Cemetery

- Chapter 3: Human Skeletal Material

- Chapter 4: Finds

- Chapter 5: Discussion of Burial Practices

- Appendices

- Bibliography