![]()

Chapter One

1914: The Call to Arms

Some years become iconic in themselves, with no further explanation or details required. They erase anything else that may have happened under the rule of their few numbers, and they indicate merely one event: 1914 was such a year.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, the city of Leeds had become one of the major industrial sites in Britain, and was generating skills and products to feed the massive empire. Its primary expertise was in engineering, clothing manufacture, dyeing and tanning. As the Victorian years marched on, there had been a proliferation of satellite industries that were spawned by the main ones, such as coal mining, ironworks and transport. All this was on top of the agricultural base too, which comprised all the bordering agricultural areas, from Wakefield in the south to Collingham and Wetherby to the north.

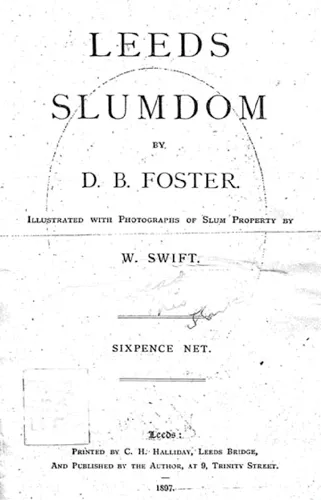

At the heart of all this there had been population growth and a steady but marked increase in urban development. In fact, in the last years of the nineties, a report on ‘Leeds Slumdom’ painted a depressing picture of the intensely red-brick terraces that were crammed into Hunslet, Holbeck, Wortley and Beeston. The worst instances of unhealthy living for the workers in the burgeoning industries were in the cellars. The report noted, ‘I cannot refrain from saying that cellar dwellings are the most abominable feature of the Judas-like greed for rent which disgraces some of the property owners of today.’ The author adds that poor sanitation was a feature also: ‘I observed that in one district a very faulty arrangement exists in connection with the street drainage … the street drain is very much more used in crowded areas than in the better-class districts.’ One of the worst examples illustrated that attempts to improve matters had caused even more problems: ‘quantities of sediment’ tended to ‘give off bad smells’ and the result was that sewer gas escaped out into the main open street.

Title page from D.B. Foster’s study of Leeds poverty. Leeds Slumdom, 1897

Leeds only officially became a city in March 1893. It was not the first borough to be elevated to city status in Victoria’s reign; Manchester was a city in 1853 and Liverpool in 1880. When Alderman John Ward chaired a special meeting of the city council that March, he held up a copy of the Royal Charter. It was a momentous occasion, confirming the fact that Leeds was a definite presence, with its own strong identity, near the end of that great imperial century.

Maps of the years just before 1914 confirm this urban growth. Beeston, for instance, in 1905, was at the end of the long tramway winding from Hunslet near the city centre, out up Beeston Hill and by Cross Flats Park. To the other side of this divide there were lines and lines of streets stretching widely across Beeston Hill and towards Middleton, where there was a colliery. Similarly, if we look at Holbeck and New Wortley in about 1890, we see a massive stretch of urban housing to the west of the London and North Western line railway. Then across to Holbeck, incorporating the Victoria iron foundry, Marshall’s Mill and the engine sheds and repair works of the railway, there is even more housing.

Yet this is not to insist that Leeds was a desperately poor concentration of oppressed workers, with no cultural life and little diversity. That is not at all true. When war with Germany broke out in August 1914, the city had a thriving higher education base, theatres and music halls – entertainment in all quarters, from brass bands to park concerts. The Edwardians and Georgians loved to sing, dance and hold parades and concerts. At the drop of a hat, there would be something community-based going on. The families were strongly bonded in close-knit areas, and working-class life was intensely geared towards self-help and support.

Around the city there were the big houses: being a place for entrepreneurs, Leeds had generated wealth, and to the north of the city in particular there were the impressive villas and mansions of the masters of industry. Partly because of the Jewish immigration earlier in the nineteenth century and partly as a result of the rise of domestic industry and piecework, Leeds had become a booming centre of all aspects of clothing manufacture, and an element of this was retail: the central market was a thriving centre of trading (it was the place where Marks and Spencer began), and around the rim of the very heart of the city at Boar Lane, the Corn Exchange and at Leeds Bridge, the clothing firms were well established.

There had been widespread construction and reconstruction in the forty years before 1900. A publication of 1909 notes:

The whole district on the east of Briggate has been enormously changed, largely through the construction of these markets as well as by the natural increase of the population. The Vicarage is gone. Vicar Lane has been widened … The fields through which the Sheepscar Beck found its way to the Aire are now covered with houses and factories.

In the years just before 1914, the city was also experiencing a degree of political turmoil. As Derek Fraser puts it, in his account of Leeds’s political life at the time, ‘The last months of 1913 had seen a big upsurge in Labour’s electoral support – 50 per cent up on the poor results of the previous year and the beginning of a full-scale strike of the council’s workpeople that was to end in defeat for the strikers one month later.’ By 1916, as we shall see in my chapter for that year, the Labour presence was important in the overall debate about conscription and pacifism generally.

With all this in mind, it may easily be seen that when war was inevitable, Leeds was destined to be a principal source of every kind of constituent that might be needed for the war effort. Then the war came. On 5 August, England declared war on Germany, as that state had invaded Belgium and attacked France – allies of the British crown. The army and navy were mobilized and the Territorial forces were made ready to move into action. By the 15th of that month, Leeds men were already on their way to the theatre of war, as the Leeds Rifles left for the front, and within a month, casualties of the conflict were being brought home.

The present building in City Square, formerly the Majestic cinema, also a recruiting office in 1914. Author

As so often happens in the story of events of great magnitude in history, there are apocryphal tales about the beginning. The Great War has plenty of these, as tragedy and drama are thinly divided from dark humour and farce. For instance, this is a supposed list of messages:

From Admiralty to destroyer flotilla at sea:

BRITISH ULTIMATUM TO GERMANY EXPIRES AT 23.00.

From Admiralty:

COMMENCE HOSTILITIES WITH GERMANY.

From flotilla leader:

IMPORTANCE OF WEARING CLEAN UNDER-CLOTHES IN ACTION IS STRESSED. THIS MAY MAKE ALL THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A CLEAN AND A SUPPURATING WOUND.

But of course, a war had been a possibility for a while, but when it came, the shock was very intense. From 28 June, when Archduke Franz Ferdinand was killed, and war for Britain on 4 August, there was a trajectory of feeling going from puzzlement to horror. Many had no real comprehension of the consequences of the assassination, including the Prime Minister, H.H. Asquith, who wrote to his beloved Venetia Stanley, ‘we are in measurable, or imaginable, distance of a real Armageddon. Happily, there seems to be no reason why we should be anything more than spectators.’

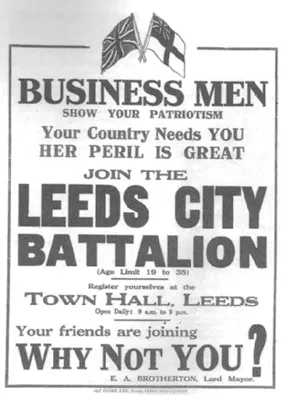

The task before the people of Leeds was summarized by their mayor, Edward Brotherton, who later wrote, referring to the first months of the war, ‘When war broke out, my activities as Lord Mayor were directed primarily to two things – the obtaining of recruits for the Forces and the continued provision of employment for the wage earners.’ He wasted no time: he held a meeting in the Town Hall, gathering together the principal employers in the area. He put the problem simply but powerfully: ‘What the future would bring forth was hidden from us, but in order to prevent distress … we all undertook to keep our factories going at least half-time.’

The effort to contribute to the determination to defeat the Kaiser’s army was immediate and resolute. A special correspondent from The Times went north just ten days after the war began and he chose as his headline, ‘The Grim Resolve of Yorkshire’. He reported that ‘the spirit of the people is magnificent’ and that adjustments were being made in industry:

Many operatives are preparing to go on short commons for the sake of their mates who have been called to the colours. At many collieries the men who remain behind have voluntarily decided to pay 2d a week to help the families of the Territorials and reservists who have been called up for service from the pits. In some Leeds engineering works the men are performing the same service in a different way. Overtime is to be worked and the pay accruing from it is to go wholly to a fund for the upkeep of the homes of fellow employees who have joined the colours.

The Territorial forces had been rationalized by legislation a few years earlier. A look through the papers, such as the Daily Graphic, in the 1890s and early 1900s, gives a very clear impression of a militaristic race: there are detailed features on training, rifle contests, summer military manoeuvres, accounts of the fleet and the latest warships, and so on. It comes as no surprise to learn that when the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was needed to move quickly to France in August 1914 and fight the first engagements, the Regular Army needed the Territorial back-up. The fact is that Germany had hatched its Schlieffen Plan – the notion that two fronts could be created, towards France to the west, and facing Russia in the east, and that men could be moved swiftly by train from east to west, as Russia would take so long to move its vast armies across huge tracts of land.

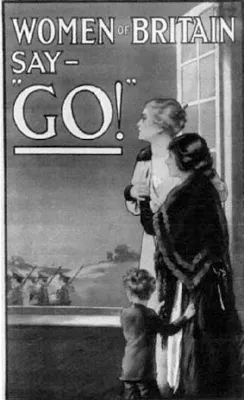

The call for volunteers came after the shock of the first encounters in France, at which it was soon realized that many more infantry would be needed to man the long lines across the front, protecting Paris and also the sea coast. If the latter fell, the Germans would have the best ports for attacking Britain.

An appeal to the suited types of Leeds to don khaki.

A typical recruitment poster. Author’s collection

Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, appealed for the new armies. The urgency of the situation was stressed when people noted that at Mons, on 23 August, the British Expeditionary Force had their first real battle and had had to withdraw. By 9 September, Fred Wilson, of the Fifth Royal Irish Lancers, was back in Leeds, invalided, and he spoke to the press:

He … says he has seen the Germans bayonet our wounded as they came across the field and forced women and children in front of them as they passed our guns. He reckons nothing of the fighting power of the Germans. ‘They are,’ he says, ‘simply whining, howling cowards. They were fairly peppered in five charges, and when their cavalry saw us coming they whined like dogs.’

That brand of morale boosting was to become increasingly common as the war ground on.

Kitchener wanted 100,000 men, and the poster calling for volunteers explained, ‘Lord Kitchener is confident that this appeal will be at once responded to by all those who have the safety of the empire at heart.’ The age of enlistment was from nineteen to thirty and men signed up for three years, ‘or until the war is concluded’.

The response for the Pals’ battalions was astonishing. Throughout the war, Leeds was to have almost 90,000 men fighting in the services, and 9,640 were killed in action. As was the case throughout the land, men would sign up for a range of regiments, but the bulk of the volunteers joined up with the ‘Pals’ or the ‘Bantams’ battalions. There was also a demand for unmarried junior officers for temporary commissions. These places were soon taken up, and within a month there were announcements that the officer places had been filled.

There were other parades and enlistments as well as those of the new ‘Kitchener’ men. The volunteers and Territorials were also keen to be seen.

One report said that there was ‘brisk recruiting’:

The Fenton Street barracks have been found too small to accommodate all the men and guns and a detachment has accordingly taken up quarters at the Headingley football ground. The 7th battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment paraded at the Carlton Hill barracks at 9. They were dismissed to their homes before noon.

There was a meeting at the Town Hall in Leeds, to start the drive for recruitment; the Lord Mayor was totally involved. This was Edward Brotherton, who figured prominently in the work for the home front. The lines of recruits appeared, and there was no smoothly efficient method of processing them with any speed. The first recruiting office was at Hanover Square, and almost 2,000 men were ready to sign up. The Tramways Committee then helped by allowing the use of their office at Swinegate for recruitment. There was also another recruitment ploy – the use of a tram, lighted, and with the destination ‘Berlin’ on the front. Fred Wilson, already quoted regarding the lack of mettle of the enemy, went with the Mayor and Lady Mayoress on the tram. The lady in question was a considerable literary figure – Dorothy Una Ratcliffe; she had married Charles Ratcliffe, nephew of the Mayor, Edward Brotherton, in 1909, and she was very much involved in war work. Her biographer, F.E. Halliday, explained, ‘During the war she helped regularly in hospital work. She assisted Edward Brotherton in his raising and equipping of the Leeds Pals … Lieutenant Victor Ratcliffe, her husband Charles’s brother, was killed in action near Fricourt.’

A page from Chums magazine. Note the influence on the new battalions – Chums and Pals. Author’s collection

The Leeds Town Hall, where so much organization for war began. Author’s collection

A Leeds tram used for recruitment. Note the destination – Berlin! Leeds Library

The Leeds Pals were, properly, the 15th (Service) Battalion (1st Leeds) The Prince of Wales’s Own (West Yorkshire Re...